by: Bill Millard

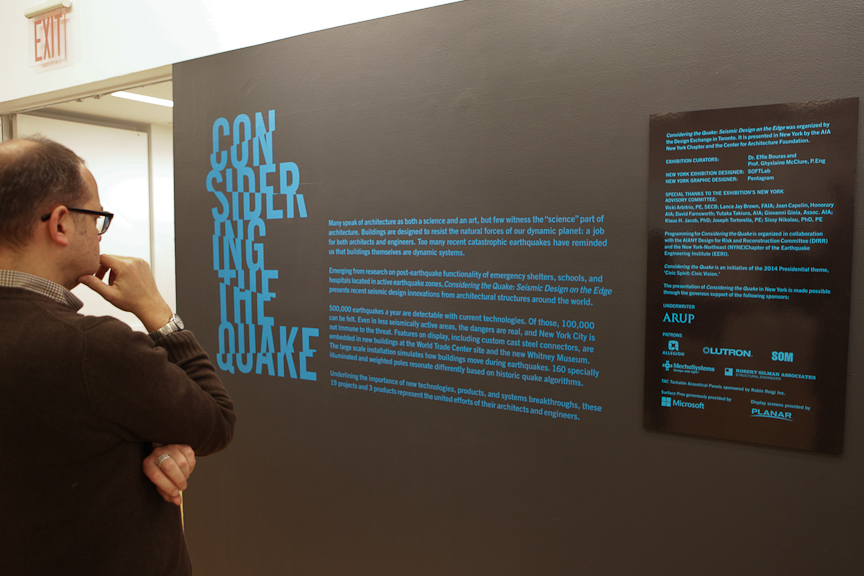

With apologies to the creators of a jukebox musical currently on Broadway, Carole King isn’t the only one feeling the earth move under her feet. While severe weather events like Superstorm Sandy have made flood preparations a prominent public concern, the AIANY Design for Risk and Reconstruction Committee (DfRR) has also kept an eye on other forms of catastrophe; the new installation at the Center for Architecture examines strategies for anticipating and counteracting earthquake damage. “Considering the Quake: Seismic Design on the Edge” is the first major exhibition in the presidency of Lance Jay Brown, FAIA, embodying an important facet of the 2014 theme “Civic Spirit : Civic Vision”. It combines detailed technical education with thought-provoking visual and interactive displays. Exploring the science and art of bolstering resilience under seismic stresses, the exhibition favors optimistic, can-do presentations of design and technology rather than images of destruction.

First mounted at Toronto’s Design Exchange last year, “Considering the Quake” now gives New York’s architects and general public a stimulating overview and a crash coursein what Brown described as “the elegant and oft-times elusive intersection between the aesthetics of architectural form and the technology of structural design through the lens of earthquake engineering.” Curators Ghyslaine McClure and Effie Bouras, of the McGill University Department of Civil Engineering and Applied Mechanics, based the work on their studies of the resiliency of emergency shelters, schools, hospitals, and other public buildings in seismic risk zones worldwide. The proliferation of “beautiful buildings that are feasible in very, very active seismic zones,” commented Prof. McClure, “is possible because all the professionals work together: the architects, the designers, and the engineers,” particularly geotechnical engineers. For every arresting new building with a dramatically cantilevered volume or an unorthodox load pattern, there’s a team of structural specialists ensuring that it can withstand seismic shocks as well as the more predictable challenges of gravity and wind stress.

Case studies explored in “Considering the Quake” include buildings in Taipei, Beijing, and Shenzhen by the Office for Metropolitan Architecture (OMA), with engineering contributions by Arup; Studio Daniel Libeskind’s Contemporary Jewish Museum in San Francisco, with OLMM Consulting Engineers; Studio SKLIM’s Hansha Reflection House in Nagoya, Japan; and work by Tipping Mar Engineers, Degenkolb Engineering, Star Seismic, and Kinetica Dynamics. Along with displays by SOFTlab and Pentagram, an array of shock-absorbing devices, and an active shake table with a seven-story building-skeleton model, the mezzanine-level window display (a thicket of manipulable vertical tubes with varied internal damping weights) gives visitors a tangible sense of how engineers counteract seismic resonance effects, which can amplify repairable levels of damage into general structural failure. Related panels and workshops organized by DfRR and the New York–Northeast Chapter of the Earthquake Engineering Research Institute (EERI) will also address earthquake preparation for professional audiences and families.

The technologies presented and discussed in the exhibition strive first to save lives and secondarily to mitigate physical and economic disruption. No building can be fully earthquake-proof, noted Troy Morgan, Ph.D., assistant professor at the Tokyo Institute of Technology’s Center for Urban Earthquake Engineering: codes call for levels of resilience that protect life, not immediate reoccupancy after a quake (a distinction that sometimes surprises property owners). Strategies for giving buildings a degree of flexibility, rather than a rigidity that would constitute fragility under seismic tension, include isolation and damping. Along with demonstrating the force-amplification measurements performed with the shake table’s accelerometers and analytic electronics, Morgan commented that a state-of-the-art isolation system, directing high forces onto a curved Teflon surface allowing a degree of lateral movement, can stabilize a low- to mid-rise building. In high-rises above about a 30- to 40-story “sweet spot,” wind forces can be a greater challenge than earthquakes, and seismic resilience strategies more often focus on viscous dampers that convert pressure to heat, safely dissipating large amounts of energy.

“In my point of view,” Morgan added, “the most dangerous buildings in New York for earthquakes are actually four- to five-story brownstones,” a dominant component of our residential stock, because masonry is inherently vulnerable. Food for thought, as public risk awareness expands from one category of calamity to another: at the first panel (02.27, “Are We on Shaky Ground? Earthquakes and New York City”) we’ll be hearing more about some fault lines that are less publicized than California’s but quite a bit closer to home.

Bill Millard is a freelance writer and editor whose work has appeared in Oculus, Icon, The Architect’s Newspaper, and other publications.

Event: Considering the Quake: Seismic Design on the Edge

Location: Center for Architecture, 02.13.2014

Speakers: Lance Jay Brown, FAIA, 2014 AIANY President; Prof. Ghyslaine McClure, P.Eng. and Dr. Effie Bouras, McGill University Department of Civil Engineering and Applied Mechanics, curators; Michael Szivos, Founder, SOFTlab; Rick Bell, FAIA, Executive Director, AIANY

Organizers: Center for Architecture

Sponsors: Arup (underwriter); Allegion, Lutron, MechoSystems, Robert Silman Associates, and Skidmore, Owings & Merrill (patrons); Robin Reigi (sponsor); Microsoft (Surface Pros); Planar Systems (display screens)