by: ac

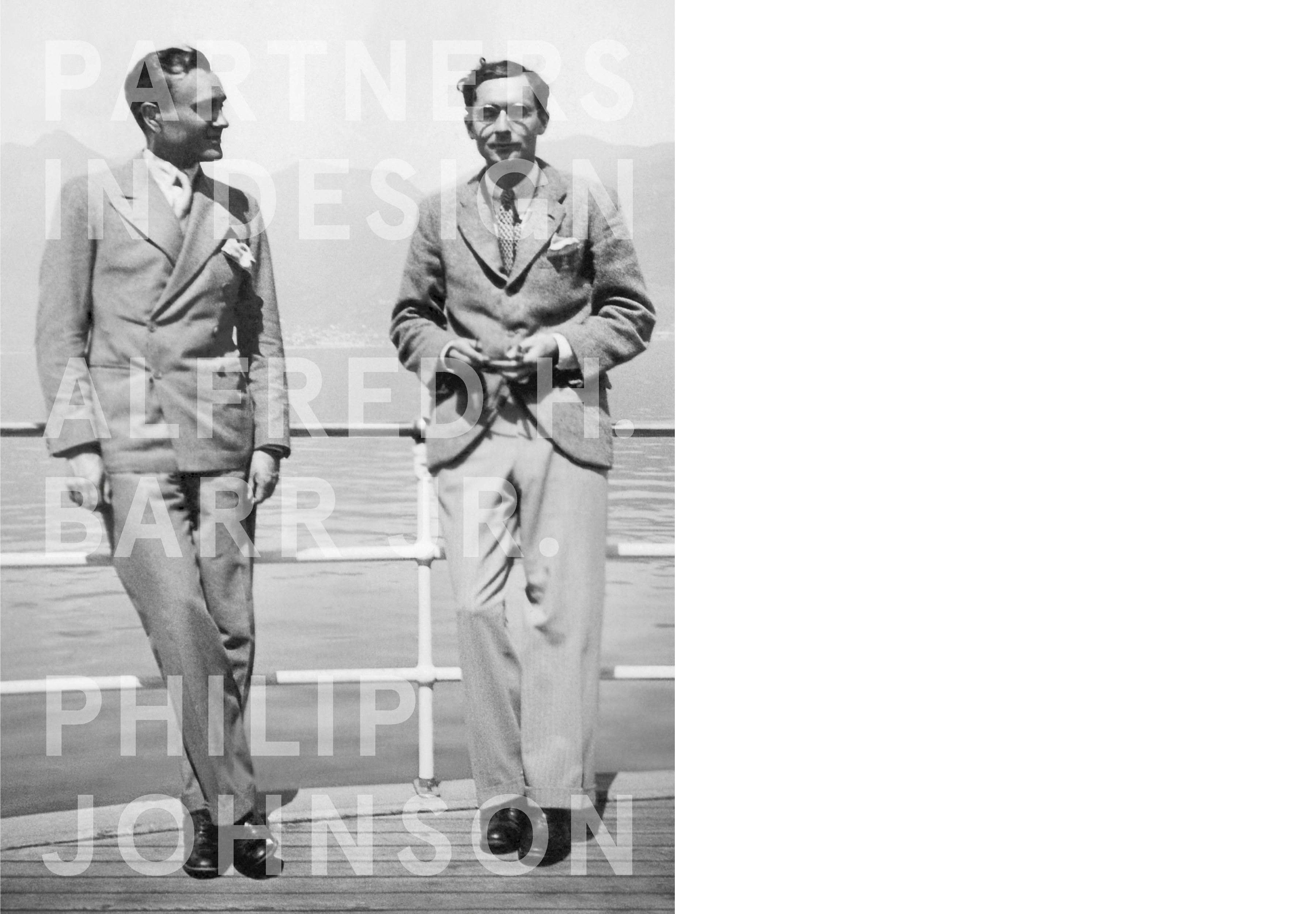

Although the new book chronicling the deep and important friendship between Alfred Barr and Philip Johnson is entitled Partners in Design: Alfred Barr and Philipp Johnson, a more apt title would be The Biography of an Aesthetic. This text expertly walks the reader through the genesis of the Modernist movement in America, from Johnson and Barr’s self-education in the movement, to how they educated the American public on the new style. Edited by David Hanks, this volume of eight essays is insightful in scholarship – a potent combination of clear visual research, endlessly beautiful photographs of Modernist interiors and artifacts, and just enough “Johnsonesque” gossip to keep many a reader intrigued.

Hank’s essays follow the arch of the creation of the American Modernist aesthetic. His piece on the Johnson and Barr Apartments describes how their passion for Modernism and the Bauhaus was expertly crafted into a philosophy within their domestic environments – one, Barr’s self-curated abode, the other designed and orchestrated by the first Philip Johnson/Mies van der Rohe collaboration. The two apartments highlight their economic differences (Johnson had money to burn and Barr created a rich environment with very little) and their shared depth of passion. One particular story noted that Barr urged Johnson to rip out the traditional door bucks and moldings to better highlight the Mies van der Rohe furniture. Johnson did not follow his advice, foreshadowing a career of compromises.

One point that comes up again and again is Johnson’s tremendous sensitivity to materials, and his prowess in manipulating them to the most dramatic end. His apartment, under Lily Reich’s direction, featured blue raw silk curtains, rosewood cabinetry, and vellum upholstery. For the 1934 Machine Art exhibition, Johnson set a collection of laboratory glass on deep, black velvet and urged the organizers to re-plate and enhance chrome finishes for the exhibition. Ultimately, the MoMA aesthetic was a rich, authentic experience rather than a visual conceit.

Essays by Phyllis Lambert, Barry Bergdoll, Juliet Kinchin and Donald Albecht round out the time period the book captures. Bergdoll’s essay on the history of the International exhibition underscores the complexity of bringing Modernism to America – just where to place Frank Lloyd Wright will always be an issue. Albecht’s dishy road map of New York’s 1930s Modernist bohemia is charming and intriguing. Kinchin’s in-depth narrative of the Machine Age exhibition expertly frames Johnson and Barr’s preoccupations, and places this exhibition as the pinnacle of the MoMA aesthetic. Included is a lovely photo album of Barr and Johnson’s European travels, illustrating the impact this had on MoMA. The final essay by Hanks, about the development of the Useful Object exhibition, describes MoMA’s traveling exhibition program in 1940s and how it “spread the gospel” of the Modernist movement.

All told, this is a highly successful tome. The writing is eloquent and brainy and new! As an artifact, the book is slightly cumbersome, but since its heritage is the MoMA catalog line, the light grey sans serif type (a bit hard to read) and awkward size will be excused because the historic photo reproduction is so darn good. For all of those who worship at the church of Modernism, treat yourself – Partners in Design should be on your bookshelf.