by: Molly Heintz, editor-in-chief, Oculus

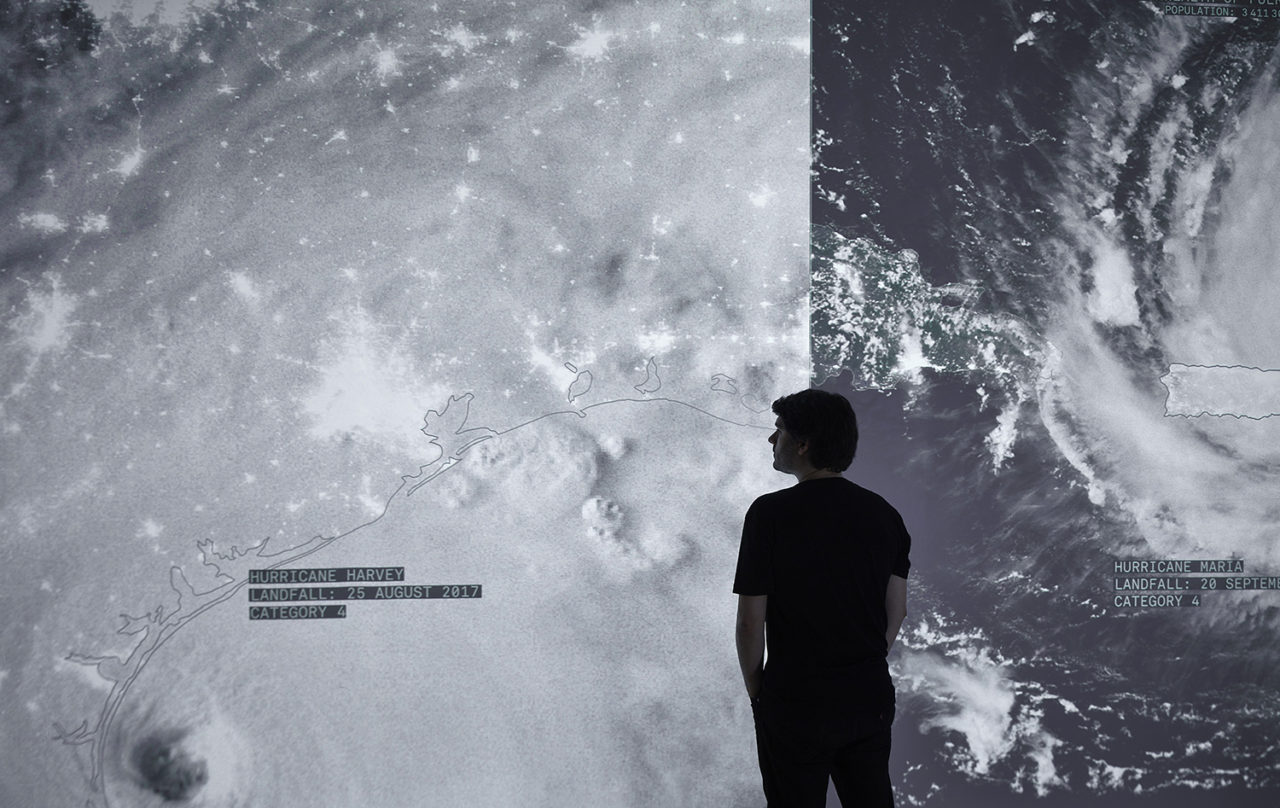

Encountering the Black Marble is a memorable moment at the 2018 Venice Architecture Biennale, which opened on May 26. Located at the heart of the U.S. Pavilion, the Black Marble is the 2012 view of the Earth at night, the dark analogue to the famous daylit Blue Marble, photographed by Apollo 17 astronauts in 1972. The Black Marble, on the other hand, reveals human activity through points of light; any recognizable geography recedes into the shadows. The image is a key element of In Plain Sight, the contribution of Diller Scofidio + Renfro, Laura Kurgan, and Robert Gerard Pietrusko, with the Columbia Center for Spatial Research, which aims to show “places in the world with many people and no lights, and those with bright lights and no people, and are suspended between day and night and light and darkness—exposed to the political and social realities of being invisible in plain sight.”

Situated in the “Global” section of Dimensions of Citizenship—the U.S. Pavilion’s telescoping take on what it means to be a citizen today curated by Niall Atkinson, Ann Lui, and Mimi Zeiger, with Iker Gil一the Black Marble is also one of the more expansive interpretations of the Biennale’s overarching theme, “Freespace.” Biennale curatorial team, Dublin-based architects Yvonne Farrell and Shelley McNamara, called for work that “exemplifies essential qualities of architecture which include the modulation, richness and materiality of surface; the orchestration and sequencing of movement, revealing the embodied power and beauty of architecture.”

While the umbrella theme of Freespace was arguably too loose to create significant common threads or emergent sub-themes, this freedom also offered the latitude for experimentation and surprise. TED design curator and Oculus Committee member Chee Pearlman noted, “I was impressed with how far the theme resonated, as curators and architects used the lens to assert relevance and seek meaningful civic engagement. Often the outcomes were powerful, if not refreshingly challenging of the professional status quo.”

Architects and thinkers from around the world are invited to participate in the Biennale, and this year a number of New York offices made stand-out contributions, from installations to events. Here are some familiar firms and faces that kicked-off Freespace last week:

In addition to DS+R, New York-based SCAPE Landscape Architecture led by Kate Orff joined the U.S. Pavilion with Ecological Citizens, an installation that considers citizenship at a regional scale, positing that regions are “not fixed political boundaries but rather assemblages of ecosystems, interspecies entanglements, infrastructural imperatives, and climatic forces.” Marsh-building units including sediment fences, fascines, biodegradable coir logs, and Econocrete micro-tide pool units take center stage and will be deployed after the exhibition on the Venetian island of La Certosa.

Andrew Berman Architect designed one of ten chapels that comprised the Vatican Pavilion on the wooded island of San Giorgio for first-time Biennale participant the Holy See. Berman’s simple shed-like structure features a broad porch that beckons passersby and connects the contemplative interior to surrounding nature. Chapels were also designed by Eduardo Souto de Moura, Norman Foster, and Teronobu Fujimori, among others.

At the Israel Pavilion, Michael Arad of Handel Architects is in good company (Louis Kahn, Isamu Noguchi, Superstudio, Moshe Safdie and others) as part of a display of proposals through the decades for the public space around the Wailing Wall in Jerusalem (Arad’s 2014 contribution is the most recent). Israel’s deftly curated In Statu Quo exhibition reveals the dynamics behind the delicate equilibrium of shared space in a city considered holy but multiple religions.

Closeby in the Danish Pavilion, Copenhagen and New York-based BIG – Bjarke Ingels Group, a design partner for the superspeed Hyperloop One transport system, presented the 10-foot sled and motor used in a critical electromagnetic propulsion test in May 2016 in Nevada. In the main Freespace exhibition, BIG took over an entire gallery with its model of “Humanhattan 2050,” aka “BIG U,” the latest iteration of a plan to make the southern tip of Manhattan island more resilient in the face of catastrophic storms and, in the meantime, more liveable and green. Farther afield at the Bauer Hotel one evening, Bjarke Ingels spoke with curator-at-large Hans Ulrich Obrist about recent work, including a museum and resort hotel for Swiss watchmaker Audemars Piguet.

Beyond the Giardini, the historic site of most national pavilions, Freespace exhibits filled the cavernous brick Arsenale, including Weiss/Manfredi’s Lines of Movement, an elegant installation considering “the potential of hybrid sites to create enduring public realms” in the face of climate change and limited natural resources. Models of iconic hybrids of landscape and infrastructure, such as the Sydney Opera House, sat on a nautilus-shaped wall whose curving interior created a mini gallery for video projections.

At the European Cultural Centre housed in Venice’s historic Palazzo Mora, the exhibition Time Space Existence features the work of multiple firms, including Skidmore, Owings & Merrill, whose two-room installation Scale + Form spotlights “the intersection of urbanism, architecture, and structural design” and spills into the three-level grand staircase with a video display.

During the Biennale preview days, ODA founder Eran Chen held an intimate event to introduce his firm’s new book, Unboxing New York (Actar, 2018), which argues: “Code, market, and zoning are words as common in the architect’s vocabulary as context, proportion and light. Consequently, the architect’s power has been pushed away from the fundamental qualities of living, towards more decoration. In Unboxing New York, ODA investigates these architecture topics to recover the power to design with quality of life as the number one objective.”