Let’s start with some numbers: 2.3 million people are incarcerated in the United States today. And though the U.S. represents less than 5% of the world’s population, 22% of the world’s prisoners are held here. A quarter of these people (631,000) are in local jails, where 70% (470,000) have not been convicted of a crime, but simply cannot afford bail. African Americans are disproportionately represented in our prison system, making up almost 40% of the inmates, though less than 13% of the total U.S. population. This means Black men are six times more likely to go to jail than white men, and a low-income Black man in America has a 52% chance of being jailed in his lifetime.

All this begs the question, why is the U.S. so addicted to incarceration? And why is the system so racially imbalanced? Is incarceration even effective at making communities safer—in rehabilitating “perpetrators” of crimes and ultimately “solving” crimes? As New York City weighs its plans for replacing Rikers Island, one of the world’s largest (and most notorious) jails, with four smaller borough-based jails, we should be asking ourselves, what can we learn from the experiment of Rikers and of the larger system of incarceration? Does this model of justice work? What should our real goal or intent be? What should future facilities for justice in our city look like to fulfill that goal?

These are the questions we set out to tackle in our second-year undergraduate design studio at the School of Visual Arts’s Interior Design/Built Environments (SVA ID/BE) program this past spring. In March 2020, just as the coronavirus pandemic was taking hold in NYC and compelling us to move our studios to Zoom, we launched a six-week design research group project on this topic. Our brief called for exploring opportunities for the built environment to promote equity, reduce rates of incarceration, and begin the process of healing in communities disproportionately affected by the carceral system. This first phase of research brought us to two overarching conclusions. The first is an approach to the programming, which we summarize as being captured by five “touch-points”—advocacy, prevention, intervention, mitigation, and reentry. The second is the spatialization of these programs which, we propose, need to be woven into the urban/neighborhood fabric.

We looked beyond the current form of the carceral system and turned to restorative justice principles to guide our efforts. Restorative justice is a community-based approach to justice that seeks to repair the harm caused by wrongdoing and to promote healing. To challenge the way the criminal justice system currently functions, this alternative shifts away from the traditional method of retribution to rehabilitation and reconciliation. By changing the understanding of offender accountability to mean making reparations instead of taking punishment, it can make way for positive transformations within the community.

In a restorative justice approach, everyone is acknowledged and given a voice. All affected parties meet to discuss experiences, address their needs, and participate in finding a resolution. These interactions benefit not only the victim and “offender,” but the community as well. Victims feel resolution by voicing their concerns and getting answers in a safe setting. Offenders are given a second chance to take responsibility, make amends, and move on without being further traumatized by incarceration. The resulting interactions create positive transformations within the community, reducing repeat offenses and keeping communities intact by avoiding prison sentences.

With its growing record of success, the movement has been gaining traction, with spaces that facilitate this approach to justice being built. In New York, the Center for Court Innovation has been creating a network of community courts/justice centers in neighborhoods around the city since its first in Midtown in 1993. And last year, Restore Oakland, designed by Deanna Van Buren and her firm Designing Justice + Designing Spaces, opened to the public, creating a hub for restorative justice in Alameda County, California.

We were inspired by these projects, but they also suggested to us that a larger, more holistic approach to the problem is necessary. We realized that, to end mass incarceration and inequities in the criminal justice system, we would need to start by addressing the root causes of incarceration and its effects on communities. Our students set out to describe the vision, programming, and design principles for a new network of spaces across the boroughs to support and promote a more holistic restorative approach to justice. Students broke into five groups, with each group focusing on one of five touchpoints:

Advocacy

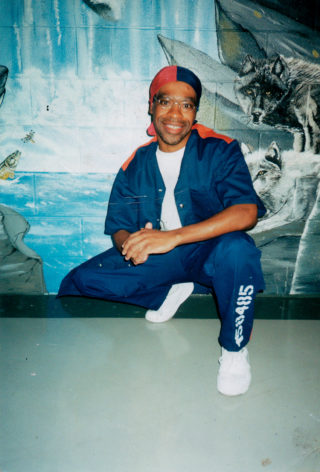

Humanizing the incarcerated and communities disproportionately affected by the current carceral system (most often low-income people of color). Proposed interventions include community forums, art exchanges, and community-generated journalism/storytelling.

Prevention

Addressing poverty and trauma, two leading pre-cursors to crime and subsequent incarceration, in neighborhoods where a disproportionate number of our city’s incarcerated people come from. Proposals include mobile solutions for educational programs, mental/emotional wellness, career services, and community-built cooperative housing.

Intervention

Repairing wounds in communities caused by wrong-doing, using alternatives to the current criminal justice system (while keeping those accused out of jail). These projects facilitate the traditional activities of restorative justice, like peacemaking circles and alternative courts.

Mitigation

Engaging with policymakers and lessening the severity for people caught up in the existing incarceration system. This includes creating spaces for advocates doing bail and parole work, as well as interventions within prisons; for research, learning, and therapy; and for reenvisioned visiting experiences.

Reentry

Welcoming returning citizens. This means assisting people recently released from prison, helping them develop the tools they need to rejoin society, and working to reduce recidivism. Projects include housing solutions, job training, space for rebuilding social bonds, and enrichment programs via the arts.

The teams defined objectives for each of these touch-points within a community and set about developing programs and conceptual designs for components within the larger network. This resulted in the foundational framework for this ongoing research project, which will be expanded on by subsequent studios in the coming years. Our goal is to end mass incarceration and inequities in the criminal justice system by addressing the root causes of incarceration and its effects on communities.

The SVA ID/BE student effort to develop and prove the concept of an infrastructure for restorative justice continues as we begin a new academic year. With collaborative support from NYC agencies and non-profit advocacy groups, including the Department of Design and Construction’s Town+Gown program and the Mayor’s Office on Criminal Justice, we hope to facilitate opportunities to engage directly with communities, to apply local expertise, and to build working prototypes that support new ideas through evidence-based research and community co-creation and feedback.

When these students enter the workforce, move on to graduate programs, or become community leaders them-selves, we see huge opportunities for a motivated generation of designers, thinkers, and doers to apply themselves to the long-neglected problem of racial disparity in our criminal justice system. We challenge the architecture and design community to collaborate with us in this effort and use the tools of our discipline to be agents of change.

Darrick Borowski, AIA, and Rik Ekstrom, Assoc. AIA, are adjunct professors of design at the School of Visual Arts Interior Design/Built Environments Program and founders of ARExA, an architectural and design research firm based in New York.