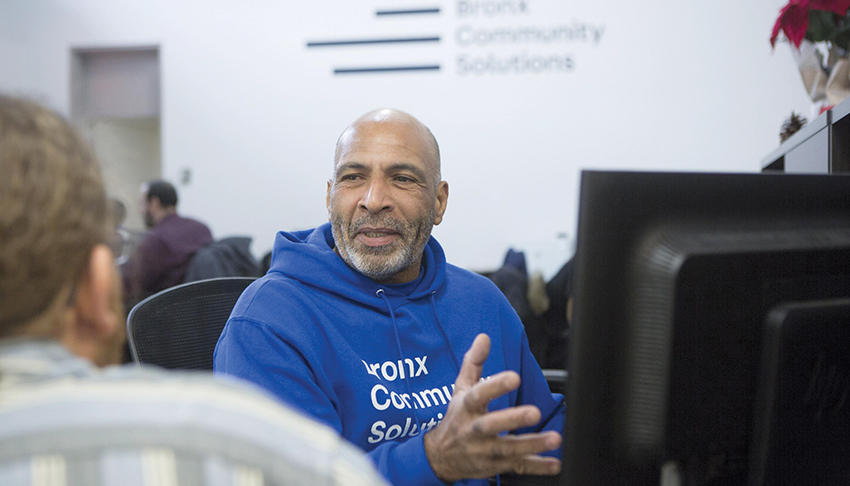

Social worker Maria Almonte of Bronx Community Solutions has an office that is 12 feet from the courtrooms within the Bronx Criminal Courthouse. The nine-story, 1930s limestone-and-granite courthouse was designed by architects Joseph Freedlander and Max L. Hausel with modern massing and a neoclassical entry pavilion, and is adorned with foliate details, copper panels, a frieze by Charles Keck, and WPA-commissioned sculptures around its base. Almonte and her 14-person staff have become the first ones to greet individuals who have just faced a judge and been directed to a diversion program to avoid incarceration.

“For many years now, we have been trying to provide different types of diversions for people who may be coming through the criminal justice system, from pre-arraignment—meaning at the arrest level—and at post-arraignment—individuals who are in front of the judge and might be looking at either a jail sentence or collateral charge as a plea,” Almonte says.

A 15-year-old program of the Center for Court Innovation, it’s an essential part of the Mayor’s Office of Criminal Justice Reform’s expansion of Alternative to Incarceration and Supervised Release, which aims to limit excessive use of detention by judges. Bronx Community Solutions offers court-mandated, supportive, community-based solutions for those charged with misdemeanors. Rather than using jail as an immediate implement, judges can refer defendants for anger and behavioral health management, community service, driver accountability programs, human trafficking survivor services, counseling, restorative justice programming, employment services, and substance-use support.

Almonte’s staff increased almost tenfold four years ago when her office helped start the Supervised Release program in the Bronx. Instead of releasing people on their own recognizance, setting bail—often beyond the means of the people accused of nonviolent or civil offenses, resulting in jail time for minor offenses—or sending the accused to jail to await trial, Supervised Release provides community-based supervision and support through non-profit agencies for those with pending cases, ensuring they return to court and avoid arrest. It’s one of five agencies citywide that provide pretrial supervision, currently managing 350 cases. “Because I’ve been work-ing in the criminal justice system and trying to bridge the gap between courts and community, I’ve come to understand and appreciate that community members value public safety, but they also value the fact that Black and brown individuals com-ing through the system are their community,” Almonte says.

In 2016, as one of the social service providers within the court system, Bronx Community Solutions convened formerly incarcerated people who advised the Independent Commission on Criminal Justice Reform to close down the Rikers Island jail complex. Almonte is encouraged by the city’s program to relocate jails to new borough-based facilities closer to the courthouses. “It’s really important for individuals who have to be placed in detention to be closer to where they’re going to be provided support systems,” she says. “That’s important when we’re trying to provide opportunities for people to be reintegrated into their communities. It needs to feel like it’s part of the community. As a social worker, I understand how valuable it is to create concrete services that are obtainable for someone to be successful. It’s one thing we have seen from our data and successful outcomes; the arrest may be the crisis situation, but you look at the underlying symptoms and help someone ad-dress those so you can stop that revolving door.”

Almonte talks about the importance of creating a sense of warmth in her office space, setting a tone that allows people to ask questions, have agency over decisions, and discuss such concerns as what kinds of employment and child-care issues might prevent them from being able to comply with court mandates. “That’s one reason why at our offices, we try to create this different feel, this different tone, the moment someone comes into our office space, which is only 12 feet away from the arraignment court they were just released from,” she says. “So it’s very intentional for us. The way we begin our interview process is to first find out if they even understood what just happened and give them the opportunity and space to ask questions. That sets the tone for us to not only allow that individual’s voice to be heard, but to find out their choices of what they are able to complete and how we can support them. Give that person a choice, and it actually increases the compliance rate for that obligation.”

Almonte agrees with the justice reforms up to now, and with the AIA New York Chapter pushing for more reform as a condition of architects working within the system. She notes the unequal treatment in policing, procedural justice issues in the courts, and external public health factors that contribute to violence. “We know it is still a system that is not equitable and has not been for a long time,” she says. “That’s a pretty bold statement for them; good for them. I hope there will continue to be more reform and legislation, especially in New York, but also in the whole country.”

Stephen Zacks (“Reform from the Inside: Bronx Community Solutions” and “Beyond a Broken System”) is an architecture critic, urbanist, and curator based in New York City. He is founder and creative director of Flint Public Art Project, co-founder of Chance Ecologies and Nuit Blanche New York, and president of the non-profit Amplifier Inc., which develops art and design programs in underserved cities. He previously served as an editor at Metropolis magazine.