DEANNA VAN BUREN

by Patrick Sisson

When people first step inside a peacemaking space de-signed by Deanna Van Buren, architect and founder of Oakland-based non-profit Designing Justice + Designing Spaces, their common first reaction is to step back. Designed to calm, slow down breathing, and lower heart rates, these communal spaces, made for two or more people to dialogue in pursuit of a less punitive form of justice, often feel too nice, says Van Buren. The victims, perpetrators, community members, and others invited inside some-times feel this is foreign to preconceptions of courtrooms, prisons, and punishment. Only later do they settle in, relax, and begin a journey towards restorative justice.

That occasional unconscious recoil at a space meant for peace perhaps illustrates the need for Van Buren’s work, which is nothing less than a crusade for reconciliation and the creation of spaces for restorative justice. This concept and centerpiece of her practice—gathering the victim and perpetrator of a crime together to mutually decide the path towards repair and restoration—offers agency and empathy that is radically at odds with the American carceral system. “People point to more humane prison designs in Europe and Scandinavian countries and ask, ‘Why can’t we just design prisons like that here?’ I say we can’t because our system is rooted in enslavement and its historical legacies,” Van Buren explains. “They basically built their values. Until we shift our cultural approach to justice and heal from our violent and oppressive past, design won’t matter.”

Van Buren’s mission, simply put, is to design space that will serve as an alternative system of reconciliation and justice. After founding her firm in 2011, she built some of the first spaces in the nation dedicated to the restorative justice concept, including a high school and community center in her current home of Oakland, California. Her approach continues to gain momentum at a moment when the Black Lives Matter movement and national protests over the murder of George Floyd have radically shifted our national dialogue on crime and punishment. (Her 2018 TED Talk espousing her vision has been viewed more than a million times.) And she’s about to scale up, simultaneously working with community groups in Atlanta to figure out how to repurpose a city jail into a larger hub for justice and community development, and embarking on the process of buying land in Detroit to develop a four-block community project she’s calling “The Love Campus.”

I am constantly learning how to wake up and be inclusive and do this in the right way,” she says. She believes the concept is catching on because the government is willing to learn and, more importantly, to listen to the grassroots community groups demanding this different path. “Folks in government need to listen to the organizers deeply connected to the community, who have been going door-to-door for years,” she says.

Growing up in a Black family living in a segregated community in rural Virginia, Van Buren felt the sting of racism, but also the draw of design and call to justice. She started building what she’d call “healing huts” in the woods behind her home, after she was sent home for punching another student who called her a racial slur. Her mother, a public school teacher who herself grew up in poverty and worked in extremely disinvested neighborhoods in Washington, D.C., ex-posed her to the realities of economic and social injustice. When Van Buren was 12, a classmate said he wanted to be an architect, giving her a name for her ambitions. Van Buren studied architecture at Columbia University and then worked for English architect Eric R. Kuhne, designing shopping centers around the globe and engrossing herself in how to translate culture into public space. Two formative experiences focused her career on justice: In 2007 in Oakland, she heard Fania Davis, sister of Black scholar and activist Angela Davis, speak about the concept of restorative justice, which struck a chord. A few years later, she visited a prison while working with a colleague teaching inmates, and observed the stark environment of incarceration for the first time. Both incidents made her question how she could make a difference. “An architect is a person who builds something, makes something, imagines something,” she says. “So I’m an architect who will imagine a system for restorative justice.”

Van Buren soon began refining her ideas with a series of increasingly larger projects. She convinced Fania Davis to help get a grant to build a restorative justice center at Castlemont High School in Oakland. Van Buren’s first such project, a pro bono effort in 2010 that consisted of some paint, donated carpet, and inexpensive lighting, proved so successful that she quit her job and launched her own firm.

As her practice has expanded—including designing Restore Oakland, a former nightclub turned community advocacy and training center that opened in the Fruitvale neighborhood last year—Van Buren has continually refined the design of peacemaking space, taking inspiration from voluminous research, experience, and indigenous practices. Compared to the imposing infrastructure of concrete, bars, and wires of the prison system, such spaces may seem insignificant at first. But the message they send, and their power to change lives, is much larger than their dimensions.

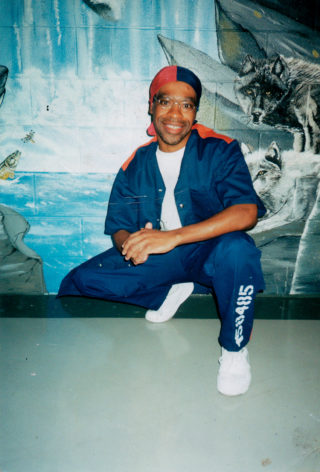

“When I visited prison, I remembered that we were meeting prisoners in the place where they’d meet their families—the best place in the entire prison,” she says. “And it was just grim. Prison is hard, and those men, mostly Black men, were no different than you or me. It was a profound experience that changed my life and committed me even more to this life.”

Patrick Sisson (“Reconceiving Justice” and “Roads, Not Walls”) is a journalist and Chicago expat living in Los Angeles. He is interested in cities, transportation, architecture, and consumer trends—and the way these forces shape culture and urban life. His writing, which also explores music, art, and technology, has been published by the Verge, Vox, Pitchfork, Curbed, and Wax Poetics. He is the author of This is Chicago, a book about the history of design and designers in Chicago, published in 2015.

Q&A: EMMANUEL ONI

by Emily R. Pellerin

Emmanuel Oni is an artist, architect, and community designer at the NYC Mayor’s Office of Criminal Justice. He comes to the practice of architecture from an atypical vantage point that centers on space-keeping framed by spatial justice. For him, architecture is not necessarily about buildings. It is about amplifying voices typically overlooked when decisions are made about the built environment, and about shifting narratives around public spaces that may harbor trauma or stigma. His approach to restorative justice focuses on how architecture contributes to the spatial divides impacting marginalized communities, and how the architectural community can repair that relationship. Here, Emily R. Pellerin talks with Oni about his recent call to action for the architecture industry, speculative and inclusive visions for Rikers Island, and the future of design work. This interview has been edited and condensed.

Last fall, you published an article in the design magazine FRAME that has been described as an “unsolicited letter” to architecture, design, and academia, all of which you’re involved in as a practitioner or an educator. You explain why you focus on community-oriented work in your own practice, and you call for architectural industries, specifically megafirms, to expand their models for hire and contribute their capital and labor to their performances of allyship. Can you expand on that?

I don’t think I’ve ever told the story of how that article came about. During the summer, there was a lot of buzz in the design world to make a Black Lives Matter statement, but also to follow through on statements of inclusion. I started reaching out to several architecture firms, noting that there are community projects to get involved with, like those at the mayor’s office. Someone reached out to me and said, “Yeah, this is great, but we feel like architects should be paid.” That’s what sparked something in me to write down why, at this juncture, especially if you’re in a corporate position where you could afford to offer some low-scale design work, you should consider community-oriented pro bono work. The letter wasn’t to that person—it was to the architectural profession as a whole. I totally agree that architects should get paid for their work. But if you’re a 500-person firm and are trying to get compensated for community work, especially when that work seems so crucial right now, something about that rubbed me the wrong way. That letter was a manifesto to the work I’m doing—not just speaking to the architectural profession, but also my call to action.

You believe the architectural manifestation of restorative justice should be driven by communities directly impacted by policing and criminalization. What are the roots of that perspective, and what could that manifestation look like?

I did my undergrad thesis on alternatives to incarceration, and it’s led me to other forms of thinking when it comes to design interests. I became really interested in the idea of death and the architecture related to death. When the pandemic happened, you could see the level of disparity that occurred, mostly in under-resourced, marginalized communities. I wanted to investigate that more. Through those investigations, I realized it wasn’t really about death, but about trauma—trauma after experiencing loss. Right now I’m focusing my work on how to respond to gun violence. At my job, I was connected with a mobile trauma unit—think of them as first responders to violent incidents. I don’t think anyone else is looking at this spatially. For instance, some people don’t want to go to a store, alleyway, or street corner because that’s where a violent incident occurred. So, in that sense, there’s a level of trauma there. How do we address that? That’s what I’m currently doing. I’ve been researching a lot about how remembrance and memorials can lead to advocacy through healing space. That’s my path for architecture.

How can we incorporate trauma and healing in new approaches to restorative justice architecture?

I don’t know if these are “new” models. Deanna Van Buren has laid out a really good pathway but, at the same time, it’s always good to have different points of view. Restorative justice is such a huge concept, so people are probably going to interpret it spatially to be quite grand. A lot of times, from an architectural standpoint, you think of restorative justice as meaning that we have to create this huge center, where all these things are happening, when, in reality, it starts off on a very small scale. Start-ing small and learning how to grow and evolve with whatever community you’re working in is really key. Sometimes it may not even involve a building. It’s thinking about how to build community without a building, or something that’s not always permanent, given that our society is prone to flux and change. That’s also something I‘ve been thinking about when it comes to healing and trauma—that sometimes it’s not always going to be a permanent memorial, but more of a ritual or practice.

Let’s say we close Rikers Island tomorrow. How can a space that harbors trauma—that is stigmatized—be transformed?

My vision entails more about the process than the final result, like when it comes to getting community input and equipping communities with the tools to help envision an alternative Rikers Island. This is where I’ve gone in my own architectural career, in terms of projecting onto a site and trying to shift that build-focused approach to a more process-driven approach. My vision is, we’ll have 20 community sessions and do the research of how to reclaim the space. We’ll take people who may have been affected by the justice system on a trip because they haven’t been able to get out of New York, and have them see how another community, like Comuna 13 in Colombia, has responded to violence. That’s my vision. The narratives of the people who are affected have to be not just part of the conversation of what’s happened there, but they also have to manifest themselves spatially. There are ways to reconstruct a space or highlight positive experiences, though they don’t have to necessarily be permanent. So, instead of showing the stories that happened on the island, it’s showing the stories of people who may have been affected by the justice system, bringing to light their lives when they weren’t inside.

Can you share more about your art practice, and how it informs your architecture and design visions?

I feel like even though I practice architecture, I’ve always been an artist. That’s one reason why my approach is wildly different from most of my colleagues’. I would highlight the word “radical.” My practice in radicalness has become a bit more subtle. I’m thinking about radicalism in a very simple sense, of going against the grain, always questioning things. I’d say that on an urban scale, what would be radical is not this huge restorative justice center on Rikers Island, but—and this is not necessarily my vision for the island—it would be making Rikers a garden. Doing something so minimal is also a form of radicalism.

Emily R. Pellerin (“Reconceiving Justice” and “Self v. System”) is a Brooklyn-based writer and communications strategist with a focus on art, design, and creative communities. Rooted in design research and journalistic principles, her strategy work concentrates on brand storytelling, content development, editorial direction, and cultural programming. Emily’s recent graduate thesis is a critical discourse on the prison uniform as an article of material culture, the design of both built and systemic carceral environments, and racial and criminal justice.