When any administrative body opts to deprive an individual of liberty based on the belief that it serves the greater social good, an extraordinary amount of modesty and restraint are warranted. We are told that the U.S. justice system allows defendants due process, equal justice under the law, and presumption of innocence until proven guilty. In practice, we know that many people get caught in “the system” for radically arbitrary reasons, corrupted by unjust and unequal processes. The mechanistic grinding of the system subjects millions to incarceration or supervision. Deep-seated legacies of discrimination go unaddressed. Countless are sentenced for crimes they didn’t commit, or are detained for extended periods because of slow trials and lack of cash for court fees, bail, and attorneys. It’s therefore completely understandable that advocates want to completely abolish or greatly reduce incarceration.

The AIA New York Chapter released a statement last September that discouraged architects from designing spaces of incarceration because of the unjust, harmful, and cruel practices within the current justice system. “We instead urge our members to shift their efforts towards sup-porting the creation of new systems, processes, and typologies based on prison reform, alternatives to imprisonment, and restorative justice,” they wrote.

Brian Lee, of the architecture and design-justice advocacy office Colloqate, states the position powerfully. “I don’t think there are moral or ethical ways in which architects can support the justice system that is foundationally concerned with the oppression of Black and brown people,” he says. “There isn’t a way we can convince ourselves that is a moral stance to take. It means we have to fundamentally rethink the justice system’s purpose and the typology altogether. Because abolition is not just demolition or dismantling an existing system. It is visualizing a new system that serves those who have been harmed by the rigors, the forces of our society that outcast people, put people in harm’s way, and put people in dire straits so much that they are willing to hurt people to survive.”

Meanwhile, long-time practitioners who have been pushing for reforms from the inside agreed with the spirit of the statement, but took issue with the idea of nonparticipation. “A lot of what’s being asked for today is a smarter and more calibrated use of the power and capabilities of law enforcement and police particularly, but also of courts, prisons, and jails,” says Frank Greene, FAIA, of STV and Greene Justice Architecture, a 30-year veteran of courthouse, jail, and juvenile detention center design and a former principal of RicciGreene Architects. “It’s absolutely the right thing to use those levers of power lightly, sparingly, and as a kind of scarce resource or last resort, rather than indiscriminately and one size fits all.”

Greene argues that it would be more harmful if architects were not engaging with the system, using the power of design to change environments to benefit people being detained. “I entered this work wanting to push back against the era of mass incarceration, because a lot of what was happening in that period, the ’80s and ’90s—because the numbers were growing so rapidly—is that facilities were being designed basically to warehouse bodies,” he says. “There was very little consideration of what to do with people when they were in the care and custody of jails and prisons—just basically house them humanely and release them to return again. No attempts had been made to address their risk and need when they were inside the system. We were pushing back mostly in courthouse, jail, and juvenile projects.”

In New York City’s jails, if not on the state or federal level, that system is definitively changing. After the 2013 acquittal of Trayvon Martin’s killer in Florida, followed by the 2014 killing of Eric Garner on Staten Island, and the 2015 suicide of Kalief Browder on Rikers Island, the demands of police and justice reform activists intensified. By February 2016, New York City Council Speaker Melissa Mark-Viverito was calling for formation of an independent commission on New York City Criminal Justice and Incarceration Reform, which would examine the sources of failure and recommend changes. The commission was led by former New York State Chief Judge Jonathan Lippman, seated and staffed by reform advocates, and aided by focus groups with formerly incarcerated people, justice-impacted families, service providers, psychologists, reform advocates, correctional officers, architects, real estate developers, and planners. Its April 2017 report, A More Just NYC, detailed policies that could vastly reduce the number of people being detained, urging that the jail complex on Rikers Island be closed and replaced by four smaller borough-based facilities.

The commission’s recommendations included reforms such as setting bail at levels more appropriate to the income levels of the detained and more closely tied to the serious-ness of offenses, less arbitrarily connected to the risk of failure to appear; changing detention guidelines for those arrested on misdemeanors and nonviolent felonies; and re-directing those with special needs such as healthcare, mental health issues, or homelessness into other programs. Three-quarters of the New York City jail system was occupied by people who had not been convicted of a crime but were indicted and awaiting trial. Nineteen percent were considered to have serious mental health issues.

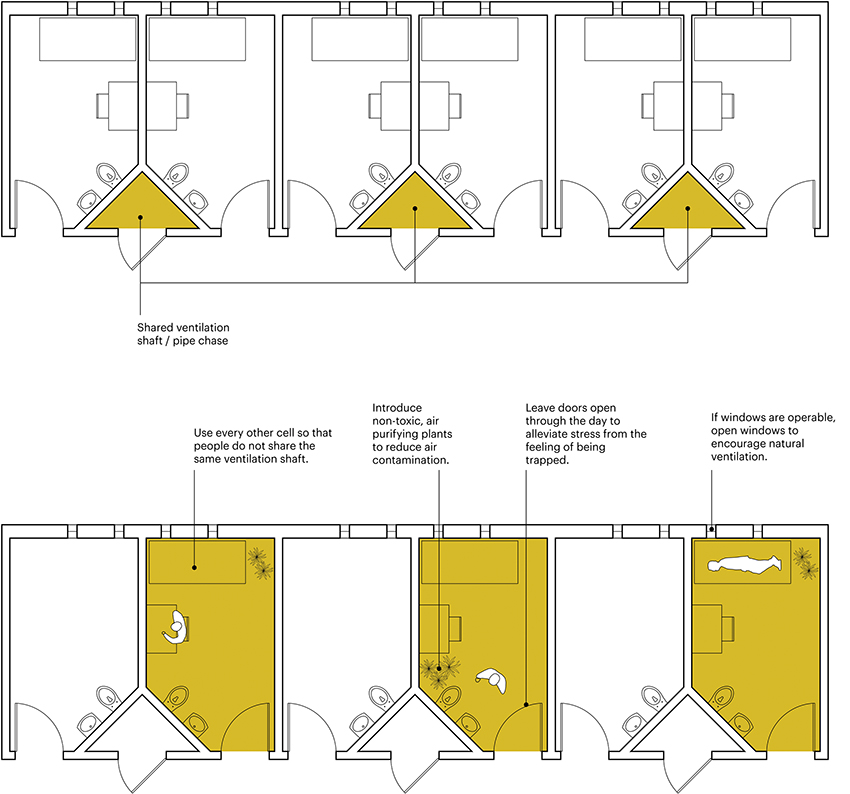

In June 2016, the city council reforms passed the Criminal Justice Reform Act, replacing criminal charges with civil penalties for many low-level, nonviolent offenses, such as open containers of alcohol, public urination, littering, and jumping subway turnstiles. Ninety percent of criminal court summons-es were eliminated in the following year. Diversion programs to assessment and community service offered alternatives to incarceration for young people and those with mental health and other issues. The city worked to clear hundreds of thou-sands of outstanding warrants for minor criminal offenses, more than 800,000 of them issued more than 10 years earlier and only 3% of them for felonies, the rest for administrative code violations, infractions, and misdemeanors. These types of judicial and procedural reforms have reduced New York City’s jail population by more than half since Mayor Bill de Blasio took office, from 10,912 in 2014 to below 4,000 as of April 2020. The reduction was accelerated by the rise of COVID-19 infections during the pandemic, supporting the argument of a report issued in May by MASS Design Group’s Restorative Justice Lab in favor of widespread decarceration. “One of the main reasons COVID is so pervasive in prisons is because of an indifference to human needs and human dignity,” says MASS Design Director Jeff Mansfield. “Prisons are designed from principles of economy, efficiency, and security, and are not designed to promote healing, restoration, or basic human comfort. As a result, prisons are stressful, crowded spaces that strip normalcy, deny personal agency, and dehumanize the people within.” At least within the city’s own jails, the institutional reforms that AIANY has called for in the justice system have already advanced significantly.

“While we are talking about these new facilities, it is a fundamental shrinking of the system of incarceration,” says Dana Kaplan, deputy director of the Mayor’s Office for Criminal Justice Reform. “It isn’t just about the different philosophy and structure of these buildings, but it’s also the importance of achieving and focusing on that at the same time we are build-ing up the infrastructure at the community level and changing the culture—not just at corrections, but also at the courts and justice system across the board, to use detention really as a last resort. When it is the last resort, we have a responsibility to ensure that people are held in the most respectful and supportive environment possible.”

The next step will be much harder: to completely reimagine and reconstruct the jail infrastructure of New York City. In many ways, the current plans to replace Rikers reflect aspirational ideas that seemed like starry-eyed idealism only a few years ago. As the Spatial Information Design Lab’s Million Dollar Blocks project argued in 2006, if we reinvested the resources spent on jails and prisons on healthcare, mental health treatment, education, and supportive housing, we could radically reduce or eliminate the need for detention facilities. At Rikers Island alone, it costs a quarter million dollars per year to house a single person.

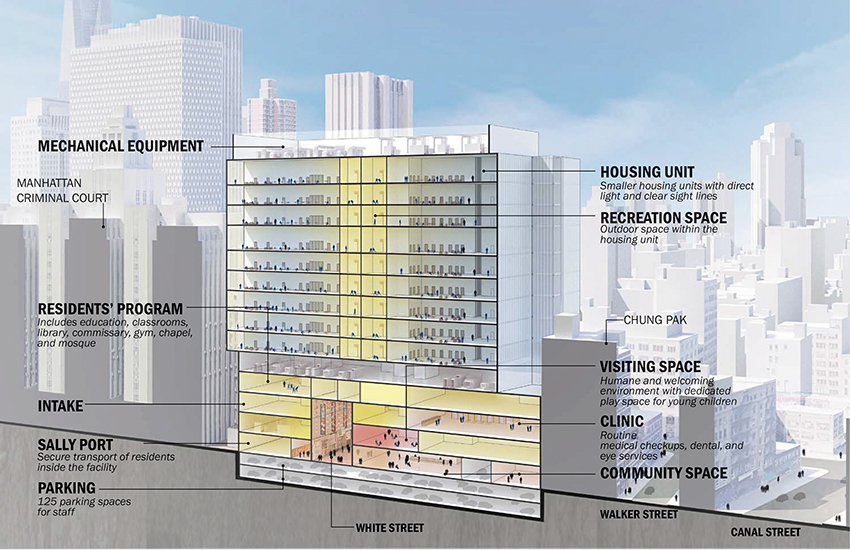

Implementing these plans will require the ideas and expertise of talented architects committed to ending the legacy of abuse that Rikers came to embody. In 2017, Van Alen Institute worked with the Boston-based firm NADAAA and a group of experts and focus groups to begin envisioning how a new jail system could incorporate the best practices for detention facilities, based on the premise that planning for release begins as soon as one enters the system. “How do we create a place where the minute you step in, you prepare for leaving, and that exit happens as quickly as possible?” asks Daniel Gallagher of DGG Architect, who worked on the project as a former principal of NADAAA. “The first step is understanding what educational, mental health, and physical health elements we could provide. What is the quickest way to get through the court system so the release can happen as soon as possible? How can we prepare folks for post-release in ways that don’t happen now—where you’re shoved out the door with a MetroCard and some minimal amount of money? How can we make places that give folks a better chance of moving beyond this experience of their life?”

Commission and design team members visited the Arlington County Jail in Virginia, Westchester County Jail in New York, the Denver County Jail in Colorado, and the Pretrial Services Agency in Washington, D.C., as examples of national models. They also learned from prisons in Europe, including the Halden Prison in Norway, considered one of the most advanced in its approach to rehabilitation. Here, detainees have easy exposure to the outdoors within a forested perimeter, and the design emphasizes sociability and personal autonomy. Noise is reduced through specially engineered security doors that don’t bang and clang, reinforcing the presumption of innocence for pretrial detainees, and, for those who have been convicted, the rehabilitative notion of “corrections” that is rarely achieved in the U.S.

“There’s widespread acceptance of this among wardens, police chiefs, legislators, chief judges, and district attorneys,” Greene says. “All aspects of the system embrace the notion that the era of mass incarceration was harmful, expensive, and counterproductive, and that we definitely need to look for and implement more enlightened approaches that are more humane; less destructive to individuals, families, and communities; and health-giving and restorative to those folks.”

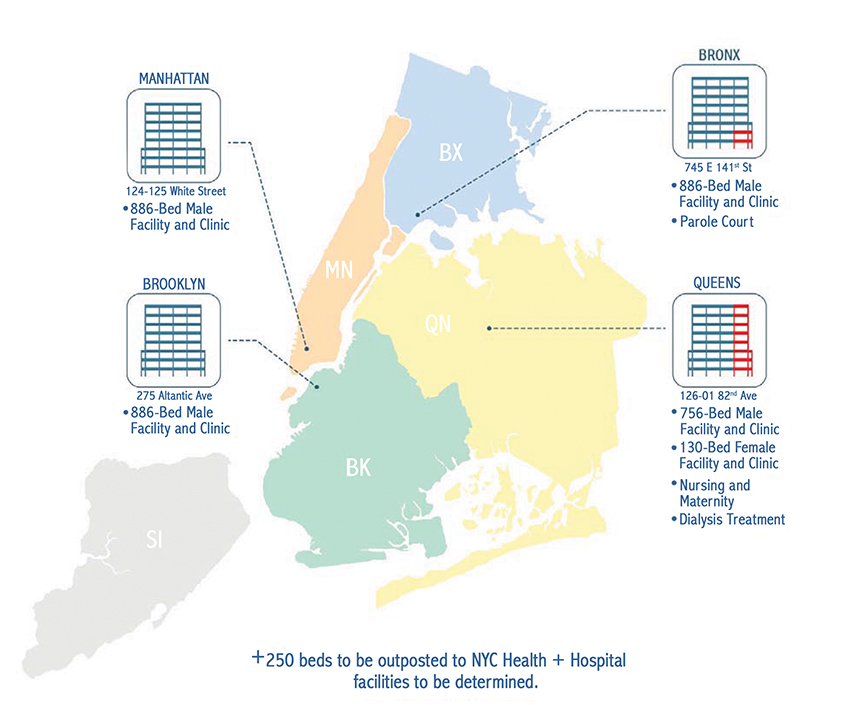

With the help of formerly incarcerated and justice-impacted people, correctional experts, and former corrections officers, the commission and design team developed a concept for the new system, sketched out drawings of the programs, and issued the report, Justice in Design, published in July 2017. Four borough-based “justice hubs” would be located closer to families, with easier access to social and educational services and greater proximity to attorneys and courts. The hubs would provide detainees with rooms offering outside views, grouped in a smaller number of units, with individual bathrooms, physical access to the outdoors, dedicated program spaces, natural lighting, and more normal environments. The new system would also reduce the extreme isolation and torturous wait times that exacerbate suffering and conflict in the outmoded Rikers complex. The Mayor’s Office for Criminal Justice and the Department of Design and Construction took on the mission of converting the recommendations into a new reality.

“I think it’s important to frame the city’s efforts to close Rikers and for this plan as going beyond the mayor’s office,” says Kaplan. “This was really a demand that came out of the movement for change, and it was something that formerly incarcerated people called for the city to do. A lot of the plan itself was shaped and impacted by those voices, perspectives, and experiences. Beyond the philosophy of these facilities, the corner-stone of this effort over the past several years has been a commitment to seek guidance from those with experience in the criminal justice system regarding what could bring the most transformation.” The city hired Perkins Eastman to do the initial scoping work, with Beverly Prior FAIA, LEED AP of AECOM in charge of drafting the remaining documents. A shortlist of three design-build firms were selected earlier this year for the Manhattan facility: Gilbane Building Company working with HOK, DeMatteis Construction Corp with Morris Adjmi, and Plaza Construction with DLR Group. RFQs are expected in the coming year for the Brooklyn, Queens, and Bronx facilities, with a dead-line set for completion of all facilities by 2027.

Prior, who specializes in jail facilities planning, praises the extensive participation of justice-impacted communities on the Rikers replacement project and emphasizes its importance. “At a forum a few months ago, Judge Lippman—the presiding judge over this idea of closing Rikers—said that Rikers is a stain on the soul of New York City,” Prior says. “Anything that gets in the way of relieving all the terrible things that Rikers represents in terms of separation from families and inhumane facilities is counterproductive. Rikers is a culture, also, and I think it’s really important for New York to shift its culture. That’s a big part of the boroughs-based jails program: to shift the culture and orientation around justice.” Behind the scenes, however, there have been rumblings of disagreement about the design-build model being introduced in the city’s contracting process for the first time on a major facility. Critics say it has eliminated the public review process that any other facility would normally undergo, limiting the oversight to special committees and focus groups. That, along-side the onerous bonding requirements of a huge construction project and the risks of going out on a limb for a process that critics say lacks transparency, may be preventing more innovative firms from getting involved. It’s not too late to revisit this process and ask whether public review should not be mandated for a project of such monumental social importance.

“Fundamentally, architects can serve a role by listening to communities that have expressed generation after generation of trauma and harm caused by the entirety of the carceral and police state,” Lee says. “They must recognize what the acute conditions are for individuals who interface with those two entities consistently, and then respond to the power system in a way that shuffles that power and allows for communities that interface with those entities to be healed through that interaction, to be put back on the course of a valuable citizen within our society.”

Greene, who consulted with the Independent Commission and NADAAA on best practices for their reports, argues for the overwhelming value of the reforms being instituted, de-spite whatever legitimate concerns there are. “This is a great initiative that I deeply believe is worthy of support, not just by the Chapter, but by architects and New Yorkers generally,” he says. “With the Close Rikers Jails program, they’re looking to make an enormous investment of political capital as well as money in building these buildings back in the community where they belong—building them smaller to reflect a much-downsized system, and focusing on risk, need, community connections, and health.”

Nadine Maleh, executive director of capital projects at the Mayor’s Office of Criminal Justice, agrees. “We have a justice system where we want to prevent people from committing crimes to begin with. We want as few people in jails as possible, and our office has been working to limit the number of people going into jail,” Maleh says. “But when there is no other option based on our system, that place where we’re holding people should have access to support services, legal services, education, and all that. Opting out makes it difficult to get innovative architects to be part of that dialogue and part of creating something that is truly indicative of the reform movement.”

In the end, there may be less daylight than appearances suggest between those working for reform within the justice system and those working outside it. Both want to reduce incarceration to an absolute minimum, and both are demanding greater accountability of the system to those who have been detained. “The only way to reshuffle power is to create new frameworks that allow a call like ‘defund the police’ to become a call for mental health workers to engage with people who are often jailed for no reason,” Lee says. “It is a call for those who are firmly for abolition of prisons to be heard as saying, not only do we want to close a useless infrastructure that holds people captive, but we want to create spaces that safely allow them to grow into active members of society in a robust and healed manner.”

If the de Blasio Administration achieves only one significant victory during its tenure—for all its shortcomings and inattention to detail—the program to reform the justice system would be a change worthy of great acclaim. Certain members of the public worry that the jails may become too good. If jails were too comfortable, wouldn’t more people want to go there? The complaint reveals how much farther we have to go in planning the non-carceral world. Perhaps after Rikers, we can think about making everyday life more humane for people outside prison as well.

Stephen Zacks (“Reform from the Inside: Bronx Community Solutions” and “Beyond a Broken System”) is an architecture critic, urbanist, and curator based in New York City. He is founder and creative director of Flint Public Art Project, co-founder of Chance Ecologies and Nuit Blanche New York, and president of the non-profit Amplifier Inc., which develops art and design programs in underserved cities. He previously served as an editor at Metropolis magazine.