Many design decisions that architects make are constrained by zoning laws, environmental regulations, and project financing. In recent years, however, there has been a growing interest in breaking through the boundaries and exploring how architecture can be used to improve the overall human condition.

The profession has engaged in much soulsearching about its potential influence on issues such as climate change and the widening gap between rich and poor. One example is the 2016 Venice Architecture Biennale, where curator Alejandro Aravena devoted much of his show to exploring ways to house the growing number of the world’s population living in slums. Landmark shows at New York City’s Museum of Modern Art have examined the foreclosure crisis and the impacts of rising sea levels.

Another example of how the profession is responding to social issues is a new Civic Leadership Program at the AIA New York Chapter. The program educates architects on how to navigate New York City’s complex network of municipal agencies and land review processes. “Not everyone can be a congressperson or a mayor,” said Justin Pascone, policy coordinator at AIA New York, “but there is a spectrum of ways to get involved. We have had architects who have worked for community development agencies, community organizations and city council members.”

Architects who have held public office say the profession has not had the impact it potentially could have. “As a profession, we have been too confined to the ivory tower,” says Jack Matthews, an architect who served on the city council of San Mateo, California, and has been mayor of the city for two terms. “We don’t have time to engage in our community, but the community needs architects in the public sphere to participate and engage with others to make decisions about the environment.”

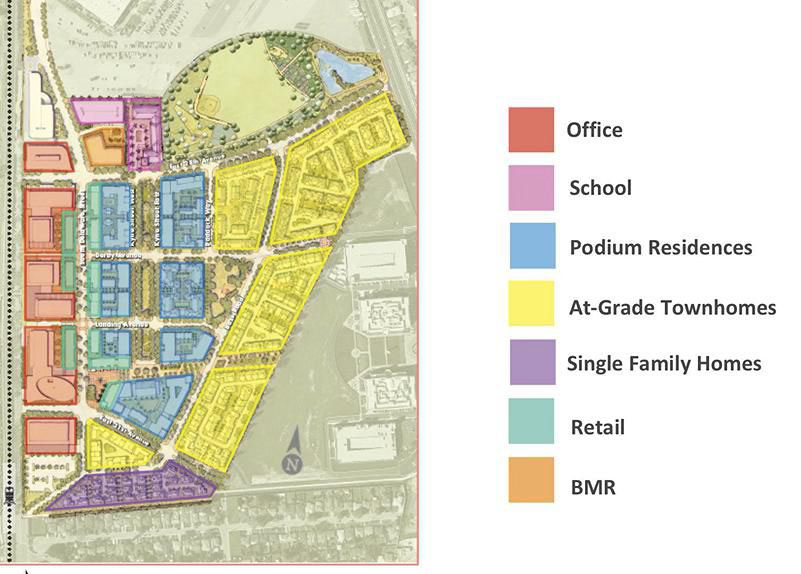

Matthews said his background as an architect enabled him to be more effective in negotiating urban guidelines for a large project in San Mateo called Bay Meadows, to make it more pedestrian-friendly. “I had some real specific influence on how the streets were laid out to provide long views and a pedestrian mall,” he said. “As an architect, you have a sense of the scale of things.”

Interestingly, the architectural profession was more political in the past. “In the 19th century, there was a big battle over whether architecture should be dealing with the social and political aspects of our nation, or be looked upon as a piece of sculpture,” said Richard Swett, an architect, former congressman, and author of Leadership by Design, a book about the civic leadership potential of the profession. According to Swett, “That battle was waged and lost on the social architecture side at the 1919 AIA convention in Nashville, Tennessee. There was a vote, and the profession decided it wasn’t important to be involved in the leadership of our society.”

In his book, Swett looks at Frederick Law Olmsted and Daniel Burnham, who rebuilt Chicago after the great fire there. “These were people who were involved with bigger issues,” he said. “Those were the examples of what I was looking at, and today the country is in dire need of being rebuilt because now all our infrastructure is more than a century old.”

However, the AIA currently does not have much influence in Washington, according to Swett. “The AIA does not have a very impressive political action committee or agenda in regard to national issues,” he said. “When I started out it was almost non-existent, and it didn’t mean a hill of beans to the AIA. They were not even taking a serious look to understand what benefits they could have from having one of our profession in Congress.”

Swett, who said he is the only architect who has been a member of Congress in the 20th century, served on a committee that dealt with public transportation and infrastructure. He said his education as an architect enabled him to be particularly effective. “Anything that had a technical background with it, I was more proficient than the rest of my colleagues in Congress,” he said, “and had a sense of how these things needed to be balanced.”

According to Swett, the profession cannot afford to sit on the sidelines anymore, and the uproar over AIA CEO Robert Ivy’s letter offering to help President Donald Trump with his infrastructure bill was a colossal mistake. “The backlash came from people who were being very shallow,” he said. “They acted as though we were offering Trump help, rather than helping the president of the United States solve a very big problem—the repairing of our infrastructure. Anyone who responds based on that kind of reaction is part of the problem, not part of the solution.”

On a local level in New York City, there are examples of architects tackling other critical social issues, such as prison reform. At a forum titled And Justice for All: Reconstructing Just Potentials, held at the AIA New York Chapter last November, sponsored by the Civic Leadership Program, NADAAA Principal Daniel Gallagher presented a plan that showed how New York City could build a more humane jail system. The exercise was inspired by the planned closing of the notorious Rikers Island Jail complex, a place rife with violence where 80% of prisoners have not even been convicted of a crime, and the average annual cost of housing a prisoner is $250,000.

Gallagher’s plan showed a system of cheerful-looking borough-based jails called “Justice Hubs,” which would enable people to visit incarcerated relatives and friends much more easily than is the case at Rikers, where visiting a prisoner can be an all-day affair. Gallagher, who developed his plan under the auspices of the Justice in Design competition, hosted by the Van Alen Institute, said his mandate was “to create a set of programs and design principles for future jails in New York, to understand how design could be an active part of the process.”

Gallagher’s firm engaged in a broad series of conversations with different stakeholders to establish how the Justice Hubs could be integrated into local communities. The system would allow for faster due process and incorporate post-release services to help formerly incarcerated individuals reintegrate into the city. The designs NADAAA developed also emphasized qualities lacking at the ten-jail Rikers system, such as light, air, and access to outdoors.

“We needed to understand how this could be part of the civic experience,” Gallagher said of the Justice Hub exercise. Summing up a sentiment that is gaining wide currency, he added, “Let’s get beyond the architecture and understand how we can connect a lot of the components in our society.”

Alex Ulam writes about architecture, planning, and culture for The Nation, Maclean’s, the Wall Street Journal, and other publications.