AI tools are simultaneously prompting age-old questions of authorship in architecture, while setting up possibilities for more collective and interdisciplinary models of labor and production. These are fundamental challenges to the authority of the current state of architecture education. I worry that the academy will be too slow in responding to these questions in efforts to maintain a status quo—a status quo that, incidentally, is increasingly becoming irrelevant because of AI. These tools are moving quicker than many realize, and I hope that educators, students, and administrators will start to think weirder and more wildly about what an AI-infused design education can look like.

In 2022, I stepped away from teaching architecture to attend grad school in the same year that ChatGPT was launched. As I eye my return to teaching later this year, I’ve realized that the education landscape has (necessarily) changed dramatically in ways I think will amplify existing cultural differences between Gen X/Boomer faculty and their Gen Z students. AI has invitedstudents to adopt completely different habits of producing and consuming media that, without thoughtful guidelines on AI tool usage and citation norms, could lead to work that is academically tired at best, or indifferent to harmful at worst.

I have been co-teaching (with machine-learning engineer Renaud Danhaive) a class on “Creative Machine Learning for Design” since 2019, which mostly predated modern generative AI models available in readily consumable formats. Our approach then, which I still believe is the most relevant to technically adventurous creative designers, was to teach a modular framework, in which the ingredients of AI—dataset curation, models of design representation, generative modeling and latent spaces, instantaneous simulation prediction, and composable multimodal goals (semantic prompts, image inputs, and physics-based objectives)—can be explored and remixed creatively to curate new human-driven processes for design.

Critique of AI is tightly wound to specific technologies, which change incredibly quickly. So I have learned not to hang critiques on whether or not certain models or tools “work.” My critical thinking in this area is more aligned with how we can best use these techniques to joyfully and effectively amplify our creative potential, to promote diverse and contextualized outcomes, and to connect with our grand challenges around carbon emissions and materials scarcity. Most of these questions are about pushing AI to more meaningfully engage with our three-dimensional, human-populated, materialized world.

I am concerned with demystifying these technologies and promoting interpretable and explainable AI models, so we can use them with a greater, shared human-computer understanding. As in fully human collaborations, I find that empathy and insights into the thinking of creative partners are critical to productive and innovative design outcomes. The current popular generative AI models conceal their training data and are therefore in many ways impenetrable as interlocutors. I am interested in promoting curiosity-driven approaches that wonder why AI models generate what they do, rather than treating them solely as solution machines.

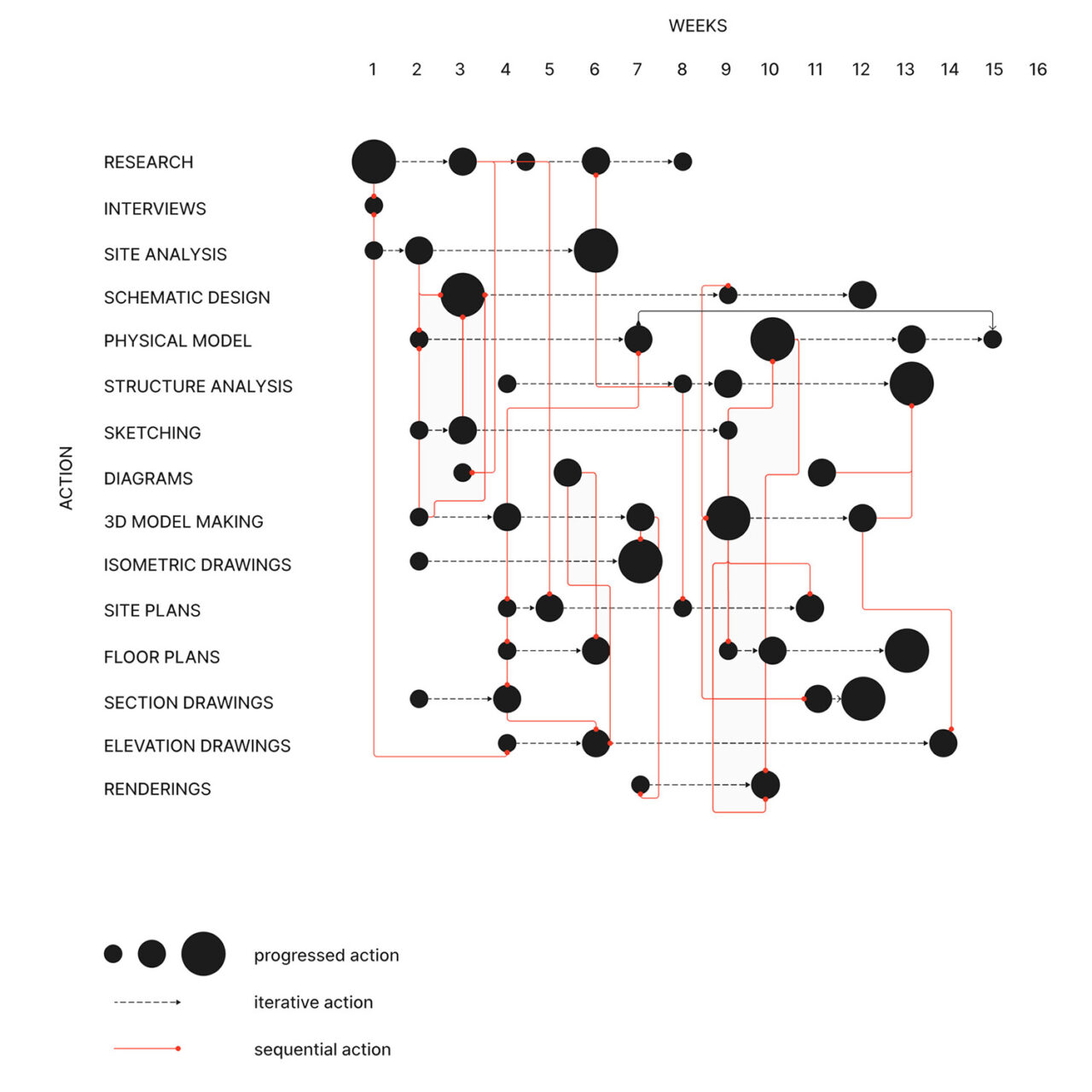

By design, the basics of using black-box generative AI are as straightforward as using Google search, so I expect this will be a skill anyone can readily master. However, integrating these tools with human expertise in fields like architectural design remains a more open question. I believe those who can develop hybrid workflows that integrate AI tools into more flexible and personalized creative processes (e.g., operating between sketching, physical modeling, CAD, AI, etc.) will have the most impact in practice.

Simply introducing AI isn’t enough. The key is to create a layered learning process with varying levels of engagement. My specific approach focuses on examining the creative cycle that occurs when human and AI-generated designs interact. Critique plays a central role in this process, allowing students to refine both the conceptual and visual aspects of their work. In addition, the academy can play a key role in promoting ethical considerations in the use of AI. We discuss potential biases in AI algorithms and the importance of selecting training data that reflects diversity and avoids perpetuating stereotypes.

To address the tendency of students to view AIgenerated visuals as the final product, neglecting the design process, I incorporate exercises that emphasize critical analysis and iteration. Students learn to filter through a vast number of AI outputs, selecting and refining the most promising ones. We also focus on developing strong editorial skills to curate a cohesive design narrative. Another challenge is the potential for information overload from the sheer volume of AI-generated images. To mitigate this, we explore strategies for setting specific design goals before engaging with AI tools. This ensures the AI outputs remain relevant and focused on the project at hand.

It will be critical for the next generation of professionals to hone their skills in two key areas related to AI. First, they should develop the ability to creatively integrate AI tools into the design workflow. This could include using AI for tasks such as generating initial design ideas, optimizing building systems, or creating high-quality visualizations. Second, they should develop a strong critical eye for evaluating and editing AI output. Mastering these filtering and editing skills will ensure that AI functions as a design collaborator, enhancing the creative process rather than replacing human ingenuity. Ultimately, architects and designers who can harness the power of AI while maintaining strong design judgment and critical thinking skills will be most valuable in this evolving landscape.

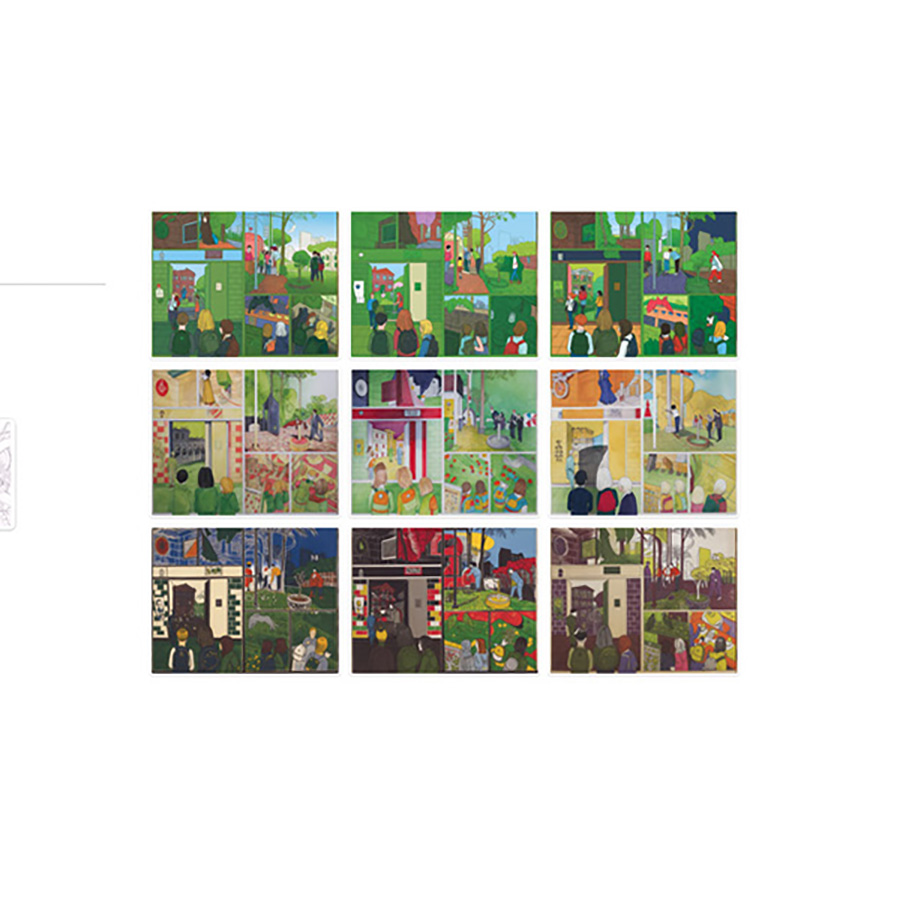

In design studios, I first started asking students to use Midjourney to generate images in 2022, when the program was released. In early 2023, I started a Discord server called “Midjourney Landscapes,” on which students and my colleagues compared their prompts—prompt engineering. Initially, I asked students to include their prompts and generate iterations of images if they decided to use any AI tools. My goal was to cultivate AI literacy. Now that everyone has a pretty good understanding of these generative AIs, I no longer require prompts to be included. And I started to encourage students to push what AI can do to help their design process. In speculative studio projects, AI blends naturally into the pedagogy. It is about embracing and exploiting the proliferation of images to visualize process-based landscapes. We recently had a workshop with Landau Design, which developed Land Kit to incorporate generative pre-trained transformers (GPT) for generating planting design based on a few lines of prompts.

AI literacy is needed. Higher education needs to have AI 101 as an introductory survey course for all students. We assume everyone needs to know math, and now the same can be said about AI and basic computational thinking, since computation is part of contemporary culture. We all need to engage with this culture.

My hope is that specialized design technologists will be able to integrate AI into the design profession to revolutionize our current unsustainable, exploitative, and toxic business model. AI should not be used as an excuse to exploit design employees for more profit. Firms need to think about how not to perpetuate the current culture of exploitation with the help of AI but, rather, how to harness the AI revolution to change the culture.

I have observed that when it comes to these kinds of disruptive technologies, it’s very rarely the academy that generates the innovations—it’s usually industry. The degree of understanding, implementation, and curricular energy is directly proportional to resources. The stuff we’re able to do within the school of architecture to change the frame of reference is a function of what we understand and how well we can leverage existing platforms.

This year we’re teaching two courses: a design course, “The Black Box: Architecture in an Age of Opacity,” taught by senior critic Brennan Buck, and “Architecture and Machine Intelligence in Theory & Practice,” which I am teaching with Sam Omans, a lecturer at Yale and the industry strategy manager for architecture at Autodesk. We are working on a course for next year that aims to make people literate in the platforms they are working on, understand where the landscape of tools is going, address questions about ethics and risks, understand the historical development of the technology and the relationship between AI and other means of architectural representation, and look at specific use cases—all under the larger umbrella of where architects have agency and how artificial intelligence affects their agency.

You can spend a lot of time teaching people the ins and outs of how to use Stable Diffusion, but by the end of the semester, the company will have released two more versions of the software, or it may be bankrupt. The problem here is putting a boat into a fast-moving river. We feel as if, pedagogically, we need to expose these folks to enough of the questions so they know what questions to keep asking when they get out into practice. Another important point: all our students have a computer we give them with all sorts of software. There are printers that print plastic, clay, and wood. There are laser cutters, CNC machines, and robots. There’s a huge downshift when they get into an office—we have exposed them to technologies to make them more interesting, qualified, and thoughtful architects. Spending a lot of time obsessing about generative technologies and images is a waste of time and a diversion. We are teaching so that students will have an understanding of the technological direction that’s happening in our industry. And we believe that’s what we have to do with AI.

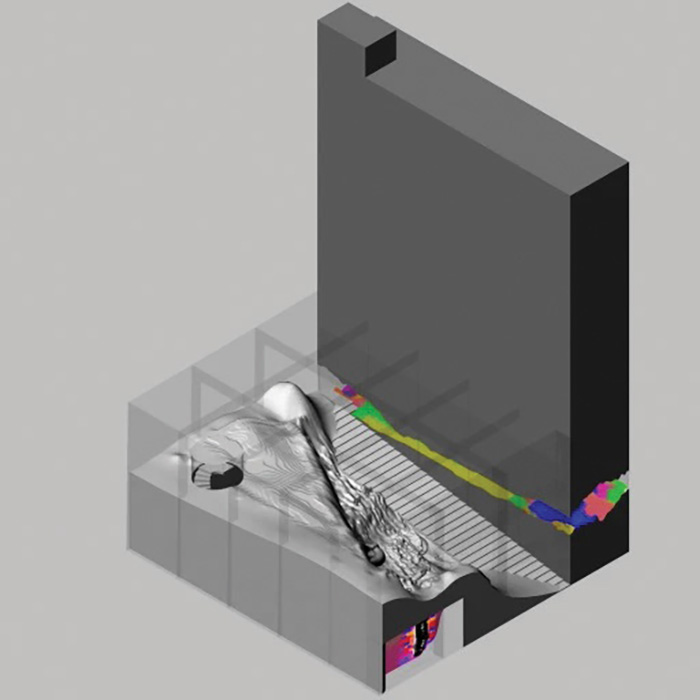

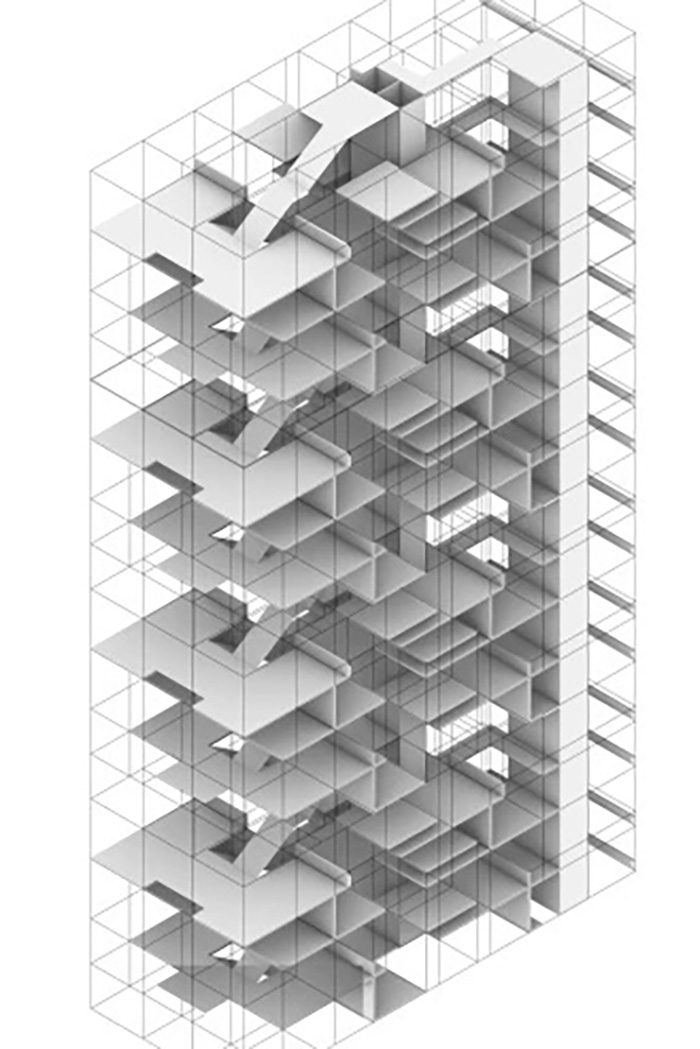

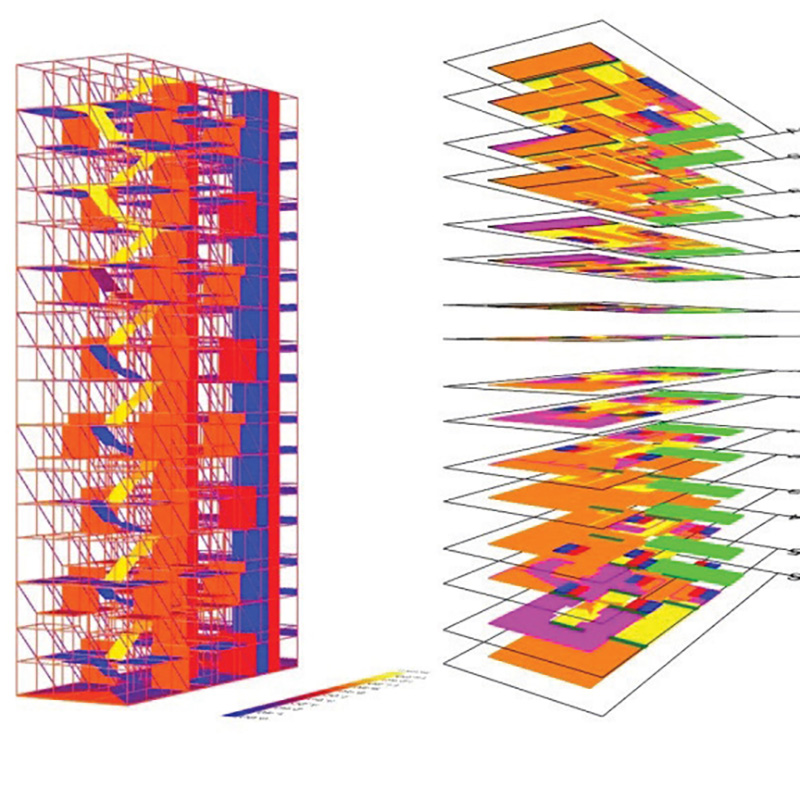

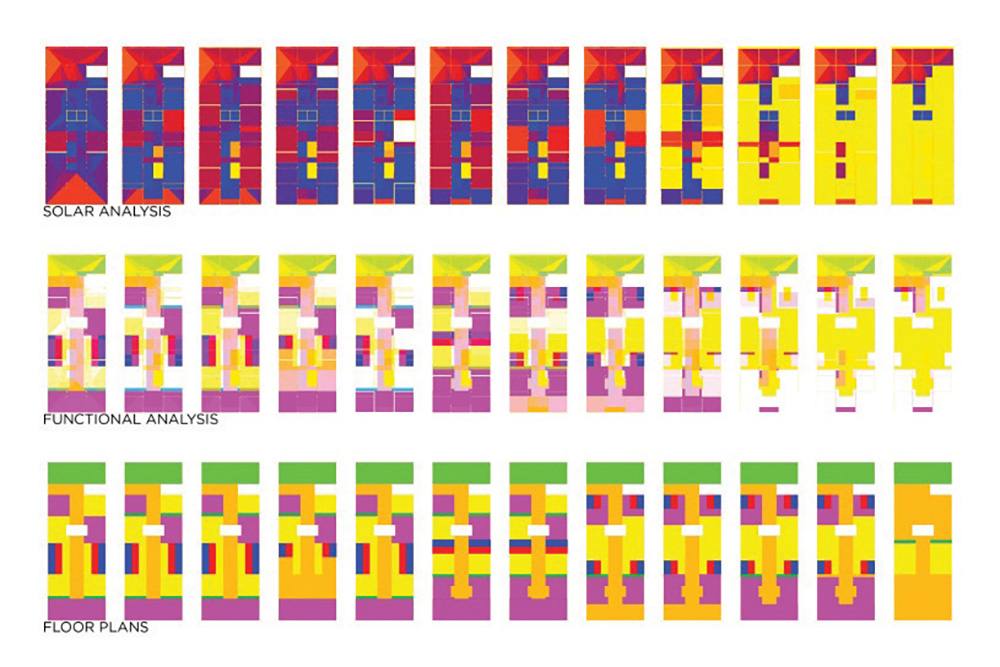

Our design studio, co-taught with professor Ajmal Aqtash from the Center of Experimental Structures (CES), is a joint effort between CES and Interdisciplinary Technology Lab (ITL) within the Pratt Institute School of Architecture and NVIDIA – OmniVerse, with a team led by Sebastian Misiurek, a design technologist and educator based in New York City. The premise of this studio is to explore “Collaborative Automation for the Construction of Higher Density Housing” for a NYC Housing Authority site. Specifically, we aim to identify potential benefits within the production process that can be unlocked to make higher quality housing more accessible and affordable. Our approach will involve using OmniVerse to develop a series of design options. Over the past three semesters, we have been deeply immersed in a comprehensive exploration of the multifaceted role of simulation in various scales, ranging from the intricate details of fabrication to the complex processes of assembly. Our interest lies particularly in comprehending the nuances of assembly theory.

The advent of AI has ignited an unprecedented wave of enthusiasm among technophiles, breathing life into a subset of architecture students that was on the brink of extinction. It’s also opening doors for those who excel in verbal and written articulation. Students are leveraging these tools to shape their narratives around architecture. They’re constructing workflows that generate scripts, voice-overs, images, videos, and soundscapes, with fully developed three-dimensional worlds on the horizon. We’re venturing into a more cinematic territory—hence more accessible to a broader audience.

In past technological revolutions, academia led the way. However, due to economic pressures and opportunities, firms, contractors, and manufacturers have surged ahead. My concern is they’ve achieved an escape velocity that makes it challenging for academia and our students to keep pace. I propose a collaborative model, reminiscent of the mutually beneficial one seen at Pratt in the 1950s, that is now grounded by a comprehensive internet protocol and technology transfer policy.

I have been integrating generative AI into elective courses and design studios, enabling students to explore it from various perspectives. In theory classes, we discuss its cultural impact on the field. In technology classes and design studios, we examine different models and their applications. We also evaluate existing generative AI products to determine their usefulness. Importantly, we create our own datasets and modify code to adapt the programs to these new datasets. For instance, students generated around 200 split-level floor plans because no existing dataset includes this information. Without this data, a generative AI model would not be able to produce split-level designs. Our students successfully developed a model that folded 3D data into 2D images to address this issue. Another student group developed its own 3D-generative AI models, creating actual 3D geometry from images. This represents a crucial advancement in seamlessly integrating generative AI technology into the design process. It marks an important transition from merely producing visualizations to generating geometry that can be incorporated into standard simulation and fabrication pipelines using conventional 3D modeling software.

Firms are seeking candidates who can leverage generative AI to enhance both efficiency and creativity in the design process. For instance, using AI to rapidly explore multiple design iterations allows for more informed decision-making early in the design phase. New hires will act as a bridge to these technologies, helping to evaluate and optimize existing tools for productivity. Moreover, firms expect new hires to be not only proficient in using these tools, but also innovative in applying them to solve complex design challenges. The ability to create custom datasets and adapt AI models to specific design requirements is particularly valued.

While mindful of the various concerns, Harvard’s urban design faculty recognizes the inevitability of AI in our future. In our core urban design studio, we introduce students to tools like Midjourney so they can learn to structure effective prompts that produce more controlled visual outputs. Regarding process, AI images become additive rather than substituting for other more foundational design principles and activities. To address some ethical and practical concerns, the urban design faculty highlight the importance of student creativity alongside AI utilization and emphasize an opportunities-based approach. A key opportunity for students involves their ability to integrate a greater volume of contextual complexity (community reports, newspaper articles, official studies, and other relevant content) within a very compressed design studio timeframe. Additionally, we emphasize the importance of critical thinking, engage students in discussions about the ethical implications of AI in design processes, and encourage them to consider the broader societal impacts of their work.

Graduates who have a basic familiarity with these tools will soon possess sought-after skills, especially as AI becomes more integrated into design workflows. For instance, in public design projects involving community engagement, pesidents typically share their desires and concerns, but they often do not participate in translating their inputs into design concepts. Here, AI tools could play a transformative role by generating images in real time based on community inputs, facilitating immediate feedback and collaboration between designers and the public. In this way, generative AI has the potential to be a power equalizer, bridging the gap between community engagement and design, a gap that has often left the public feeling disconnected. As such, part of my responsibility as Harvard’s urban design program director is to anticipate the skills and knowledge needed to thrive in a rapidly evolving field and to prepare our students to be leaders in these industry innovations.

BETH BROOME (“The New Frontier”) is the former managing editor of Architectural Record and a writer based in Brooklyn.