In 2024, architectural practices—and the practice of architecture—are being tweaked in a variety of directions, reinventing the profession in a number of ways. The proof is visible in a variety of subtle shifts and trends: The AIA has begun to admit non-architects to membership; many firms are combining architecture with other design work; unionization drives have altered compensation and culture within practices; and unexpected collaborations have transformed the work that is executed. Firms have also become far more active in taking on or seeking out projects that align with their values, as gender equity, decolonization, and decarbonization have become pressing challenges. Evelyn Lee, FAIA, NOMA, the 2025 AIA president-elect, is dramatic proof that an architect can help solve challenges outside of form-making and built work: She is the global head of workplace strategy and innovation at Slack Technologies, and has been a consistent advocate for rethinking traditional models in business and in architectural practice. Colleagues see Lee’s appointment as a nod toward the profession’s need to accelerate its thinking around technology and demonstrate how many aspects of life can be improved by architectural thinking. As chair of the AIA’s Young Architects Forum, Lee also launched a Practice Innovation Lab in 2018, seeking to spark new ideas in firm organization.

Newer, smaller firms inevitably are at the forefront of nimble, future-oriented models for architectural practice, but may lack certain institutional knowledge and resources. According to the 2020 AIA Firm Survey report, 60% of its 19,000 member firms have five or fewer employees. Some chapters are intrinsically attentive to firms of this scale; others may not be. Matt Bremer, the 2023 president of AIA New York, launched the Small Firms, Big City initiative during his tenure in an effort to redress an absence of services to small firms. “Every large firm in the country has a significant office in New York, and therefore in AIANY, and while there is a lot of small firm representation, I found there really wasn’t enough,” he says.

“Medium-sized and large-sized firms are much more apt to harbor a lot of their intellectual and trade secrets,” Bremer explains, “whereas smaller firms are always trying to figure these things out.” His aim was simply to open up channels of communication for these smaller firms, creating an “open-sourced network hub for small firms to share ideas.” Much of this information is extremely practical, touching on staffing, human resources, or payroll needs. Bremer, the founder of Architecture in Formation, notes he shares a bookkeeper with an interior design firm. There are also vital collaborative, creative possibilities in linking smaller offices.

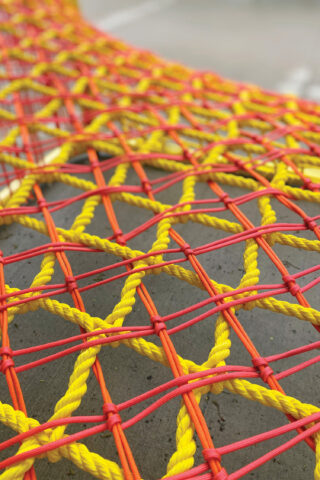

WIP: Work in Progress | Women in Practice is one such example: a collaborative effort that enables participants to pursue larger projects that interest them when they have time on hand. Elsa Ponce, who heads her own design and architecture studio, helped launch WIP in 2020 with an inaugural streetscape project, Restorative Ground, in Hudson Square. Ponce, along with several other female design professionals, founded WIP with the goal of avoiding firm hierarchy, as an effort, she says, to “move away from the typically male, single-author, or single-genius creator model.” WIP, she explains, is “horizontal—we are not a hierarchy, which is different from many architectural practices today.” Involvement of the principals varies project by project, with two leads for each, and shifts depending on available time or interest.

Projects undertaken are also rooted in genuine interest, more than a need to keep a ledger balanced. “We are very inspired by the grassroots non-profit ethos of mutual action we observe while working with our clients,” says Ponce. “They are more than clients; they are partners.”

Verda Alexander, co-founder of the design company Studio O+A, and Maya Bird-Murphy, founder and executive director of Mobile Makers Chicago, founded the initiative Alternative Practice as an effort to document and disseminate models of different modes of practice. Their stated goal is the “collection of portraits that aims to detail how design professionals are reimagining practice itself to better address the inherent failures of our social, political, and environmental systems. Only by providing alternative paths to practice can these systems be redesigned.” (They feature WIP in their list.)

The question of how firms might operate in a manner that isn’t purely reactive—choosing only from clients that come along—has attracted increasing attention from an assortment of quarters. The podcast “I Would Prefer Not To,” conceived and produced by MIT’s Critical Broadcasting Lab and presented in collaboration with The Architectural League, shines a spotlight on architects’ power to turn down work.

Along those lines, Alessandro Orsini, co-founder of Architensions, a hybrid building and research practice, and assistant professor at Columbia University’s Graduate School of Architecture, Planning & Preservation, organized a conference at the university in November 2023 called Rethinking Practice: Climate, Equity, Labor, seeking to “prompt models that allow architects to reclaim agency over the design processes, ethics, and the condition of labor under which architecture operates.”

Orsini’s prime concerns surround the “financial and political entanglement of the profession” from networks of material sourcing, systems of finance, labor and equity issues, and climate. He cited collaborative housing projects as a means to avoid typical channels of financing and a variety of smaller undertakings that “form new connections among workers, architects, clients, and the built environment.” These are obviously harder to finance than projects for which a client turns up with a budget and may require a certain lean scale. Orsini noted that conference attendees concluded that an office might do best to remain small if it was to remain fixated on values. “Everybody acknowledged the fact that after a certain number of people, you’re just feeding the office—you feel responsible for workers,” he says.

One obvious tweak in practice has been nascent unionization efforts. There are now two unionized firms in the U.S., both located in New York City: Bernheimer, which began contract negotiations in 2022, and Sage and Coombe, which did so in 2023. A few other unionization votes have failed in recent years.

Chris Beck, AIA, who helped organize the union at Bernheimer, notes that “the biggest change in the office is not what we care about, but how we go about addressing and implementing the things we care about. In this sense, the office has become much more democratic. Everyone at our office would say we have increased transparency around decision making, and people feel they have more buy-in.”

Andrew Bernheimer, FAIA, his firm’s founder, believes most elements of practice have not altered. He did explain some inaugural difficulty: There was no architectural union text to copy (“we couldn’t use the firefighters’ contract!” he says). Bernheimer’s contract negotiations involved automatic cost-of-living salary increases and more time off. These have not been, to his mind, a notable burden. “What I found was that these costs might lead to a defensible and acceptable change to our project fees,” he says. “We’re good at our job, so the client shouldn’t mind if we charge a little more if we’re still within the market rate.”

Bernheimer suggests there is a larger issue at play within most firms. “The problem to a real extent is that architects don’t charge enough to create a healthy workforce,” he says. “You do a project that should take seven weeks in five weeks, therefore you have labor working unhealthy hours all the time.” Noting that plenty of projects have union labor requirements for construction employees, he asks, “Why not architects?”

In other corners, the rigid definitions of what a practice should and should not do are loosening and broadening. Brooklyn’s SITU Studio is an unusual example of a fabrication studio that grew into an architectural firm. Michael Brotherton, a partner there, says that “about five years ago, we reached a point where we realized we’re a design practice,” which is how the firm now styles itself. The team members are happy to embrace a diverse identity spanning building fabrication and research, and are pleased with cross-fertilization between these elements.

Another high-profile practitioner who trespasses traditional boundaries, Jamaican-born architect Sekou Cooke has become known for his Hip-Hop Architecture efforts, including a book and a children’s camp, which seeks to act “as a catalyst to introduce underrepresented youth to architecture, urban planning, and design.” Projects by Cooke’s eponymous Syracuse-based studio freely span building, exhibitions, writing, and more. He is also a founding member of the Black Reconstruction Collective, which is committed through funding, design, and educational support to “dismantling systemic white supremacy and hegemonic whiteness within art, design, and academia.” The group most recently awarded its $10,000 annual prize to writer and activist Zoé Samudzi and to the interdisciplinary art practice Black Quantum Futurism, with support from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation.

With increasing cross-disciplinary collaboration happening at every level of architectural practice, the AIA has already opened its gates beyond accredited architects in offering Allied Memberships. “These professionals, such as engineers, builders, and city planners, are vital in our collective effort to solve problems through design,” said Kevin Watkins, AIA’s chief membership officer. They “help promote a more holistic and inclusive vision for the future of our industry.”

Conversely, the applicability of architectural education to a variety of other fields has become more valued. SITU’s research arm has been active in a wide variety of forensic research. Forensics Architecture at Goldsmiths, University of London, is a prominent research agency that has been turning architectural expertise to a variety of conflict, crisis, and disaster circumstances since 2010. And, in early 2024, The New York Times hired a graphics/multimedia editor with 3D-modeling experience.

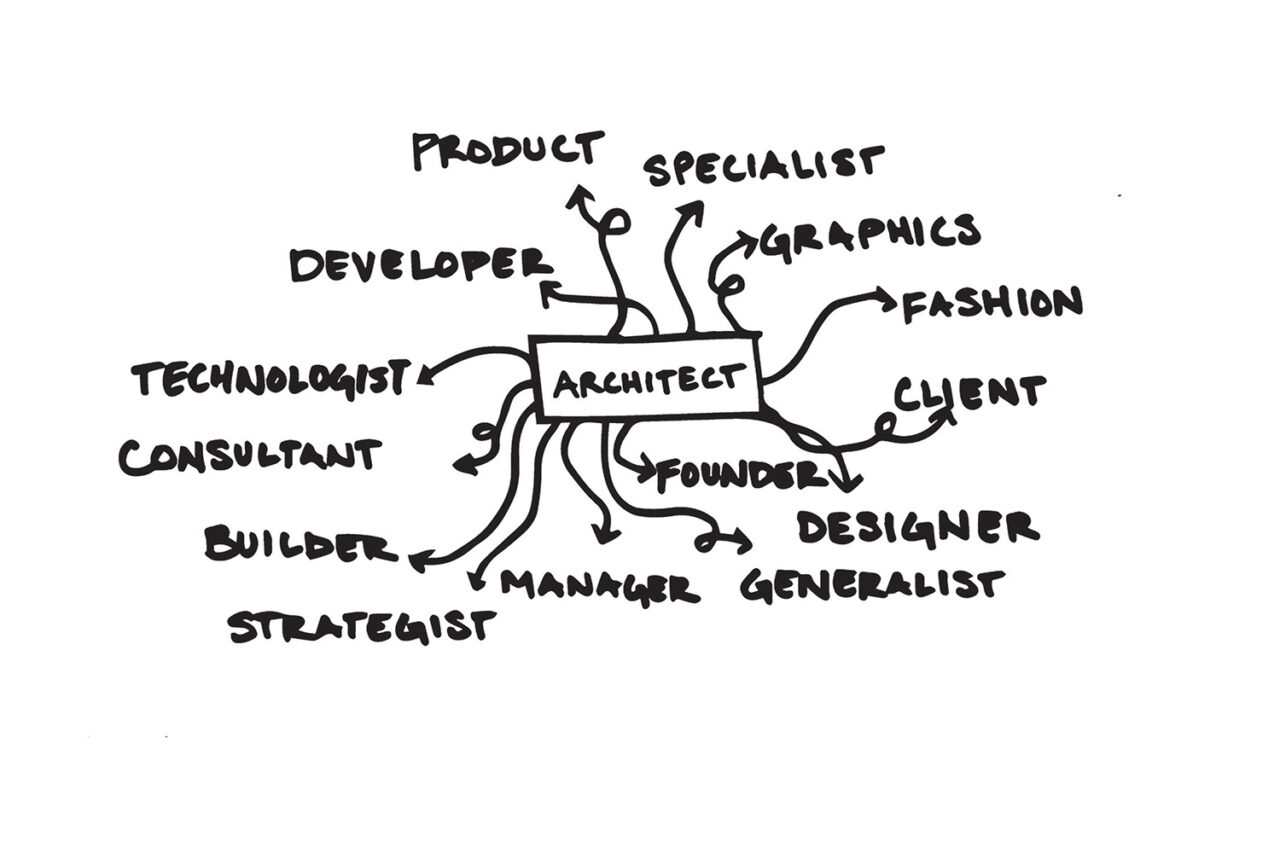

There is also a growing sense that the practice of architecture need not entail work in a licensed firm. Harvard-educated designers Erin Pellegrino and Jake Rudin founded the career consulting firm Out of Architecture in 2018 in an effort to help guide others who have left the field or want to find meaningful careers in adjacent fields. “I think there’s a huge identity crisis that is attached to becoming an architect,” says Pellegrino. “The mindset is that the pathway of architecture is singular and linear, a traditional firm practice. We’re not told that with your degree you can do all these other things.” Rudin adds: “These alternative careers are multifarious, including tech startups in the architectural space, industrial design, furniture design, narrative design, video game design, workplace design, retail design, 3D modeling, and much more. Architects are incredible expert generalists—they can do almost anything.”

ANTHONY PALETTA (“Models for Improvement”) is a contributor to The Wall Street Journal, Metropolis, The Architect’s Newspaper, Architectural Record, Financial Times, and other publications. He lives in Brooklyn.