by Nikil Saval, with introduction by Sarah M. Whiting; produced by Ken Stewart, Paige K. Johnston, and Kat Chavez

Co-published by the Harvard University Graduate School of Design and Sternberg Press, 2024, 112pp.

A Rage in Harlem puts us on stage with Nikil Saval—former n+1 editor, writer, progressive activist, and then-candidate for Pennsylvania State Senate—and Sara Whiting, dean of the Harvard Graduate School of Design (GSD). We are transported to deep COVID time, distanced and on Zoom. George Floyd’s murder is fresh, masks and anxiety are everywhere, and the 2020 election is weeks away. Saval’s talk on October 29, 2020—part of a virtual event series at the GSD—and the ensuing book tell the story of Black feminist writer June Jordan and her unlikely collaboration with R. Buckminster Fuller on a project called Skyrise for Harlem, a futuristic vision born from the aftermath of the 1964 Harlem riot.

While I at first found the book overly didactic in setting the stage and starting with a transcript of the 2020 talk, this introduction is fitting for what comes next: Saval’s take on June Jordan’s response to the killing of James Powell, an unarmed Black 15-year-old, who was shot by off-duty police officer Thomas Gilligan in front of Powell’s friends and several other witnesses. Hundreds of students from Powell’s school, and eventually an estimated 4,000 others, participated in violent demonstrations from July 16 to 22 of that year. As Mark Twain famously said, “History never repeats itself, but it does often rhyme.”

I’d never thought of the concept of nested time capsules before, but about halfway through the book, I couldn’t get the visual out of my head. Rage is academic, reflective, and rhetorical, more a retelling of a lecture, which describes a moment in design and planning that came about because of a story of violence. Saval is the ideal narrator for this disquisition.

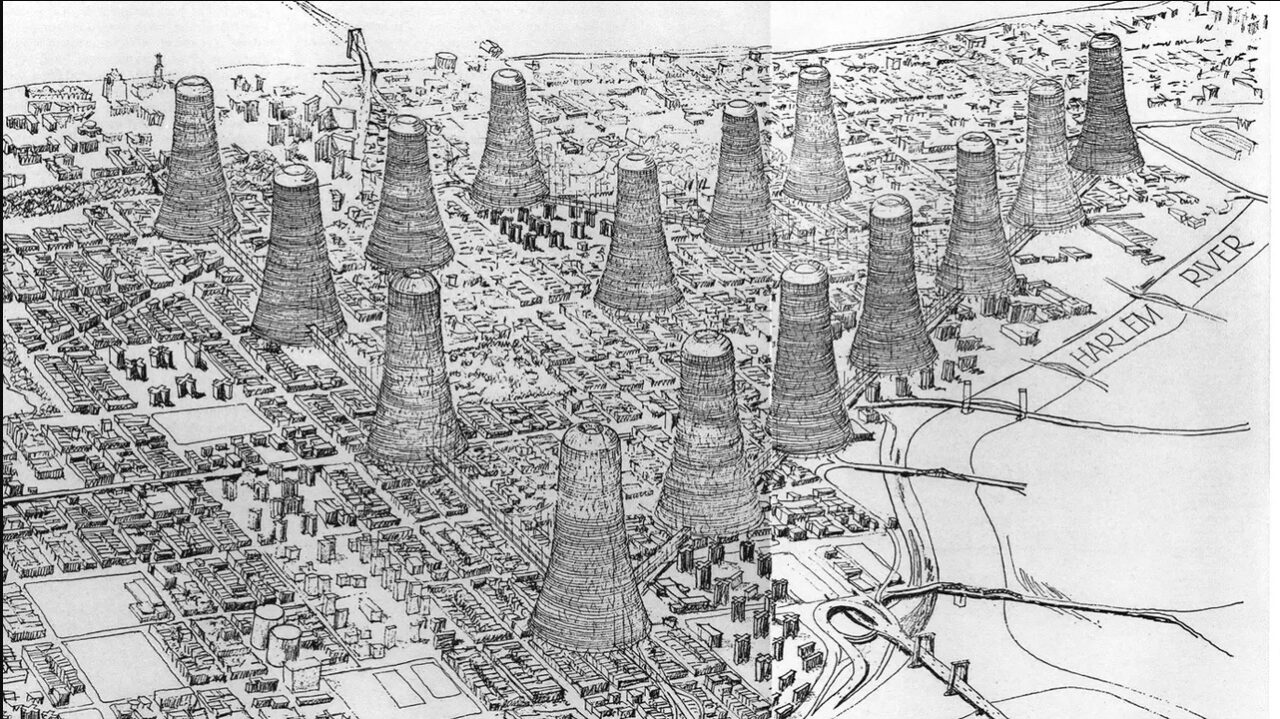

The title, A Rage in Harlem, is itself a time capsule. Though not referred to, a 1957 Chester Himes book of the same name, made into a major motion picture, portrays an earlier Harlem of millionaires, schemers, and dreamers. The streets have the same numbers, but a very different focus. Saval’s retelling of June Jordan’s journey to a partnership with Fuller comes not from fictional capers, but from real pain. Jordan and Fuller’s solution to the harm, poor conditions, and unrest is what we’d presently call a modernist, retro future: bombastic, tone-deaf, megalomaniacal. While today we’d convene design charrettes, engage the community, and conduct stakeholder mapping, Jordan and Fuller’s plan runs highways through most of Black and Spanish Harlem, obliterates the grid, and puts everyone in what would appear to be nuclear cooling towers. This is the fix. The information is disseminated not at any of Harlem’s many churches or public housing complexes, but in the pages of Esquire magazine. Neither Jordan nor Fuller grew up, lived, or worked in Harlem.

The book made me reflect during a lazy afternoon party at a friend’s apartment in Lenox Terrace. From his balcony, my friend gave a mini tour and history lesson on his corner of Harlem, pointing out sites that were historic, tragic, joyful, and chaotic. He noted a mix of drug corners, venerable YMCAs, regal churches, and ballrooms, where songs, debates, and gunfire had rung out before and after the events that Skyrise sought to solve. The vista from this one vantage point alone put on vivid display the complexity that is and has been Harlem.

In reading Rage and contemplating even a speculative project, I was struck by the lack of context at the time of Jordan and Fuller’s collaboration—and also in Saval’s text. Amid this development, where would residents deliver speeches on liberation? Protest injustice? Celebrate births and other milestones? Certainly not along the new expressways, separated from the housing, or in the private car parks, private elevators, and private balconies. Add to this the doubling of the average house size, and what would seem to come into view is a Metabolist version of a suburban subdivision, with the intention of pacify-ing a restless populace while also fulfilling a Robert Moses-like dream of getting commuters between Long and Island and New Jersey without friction.

Saval understands this disconnect and reminds us of Jordan’s bona fides, including her writing about Freedom National Bank, an African American-owned bank that served Harlem’s Black community, and the 1963 film The Cool World, about a youth gang in Harlem. That said, looking back from today’s current polarization, looming election cycle, racial animus, and Black Lives Matter backlash, it seems an oversight not to ponder what Jordan and Fuller’s speculation might have wrought—particularly with the return, during the pandemic, of the doom-loop narratives. The plan put forth by Jordan and Fuller would make even the most hardened anti-urbanist or white supremacist blush. It is surprising, then, that Jordan and Fuller get a pass from Saval on their wholesale destruction of neighborhoods with-out consent. Interestingly, Saval, Whiting, and the audience that night cast their aspersions not toward Moses, Fuller, or Corbusier, but—you guessed it—toward Jane Jacobs.

With this turn, coming toward the end of the question-and-answer portion and also transcribed, is another untested layer: the academy’s continuing worship of modernism and its current mood, which sorts out heroes and villains. What is interesting is what is unspoken or, as this is a transcript, unwritten: the fact that current practice in planning—and Saval’s own ethos—leans toward the vogue for community land trusts, and empowerment and agency for the underrepresented. The contrasts with the process and results of Jordan’s collaboration could not be further from best practices, but seem to be lauded and unquestioned nevertheless.

The book left me wondering about its intent. Is the point that Jordan’s works get put in the canon with those of the big boys, despite the outcome being anathema to democratic, humane city-making? Or is it that a wider range of people, even poets, gave up on cities and felt that destruction was the only salvation? A benefit of Saval’s work is that, in the end, Skyrise for Harlem seems like a frame around which the personalities, politics, and policies of the era can expand our understanding of how cities are dreamt of, made, and reshaped. What is clear is that bad planning didn’t get in the way of good storytelling.

Note to the authors: Jordan lived in Queens, not Brooklyn. Also, the book implies that Esquire editors decided not to credit Jordan for the design, but this conflicts with a 2020 New Yorker article stating that Jordan herself omitted her own role in the process in the Esquire piece, and emphasized Fuller’s.

Editor’s Note: A Rage in Harlem: June Jordan and Architecture is the 10th title in The Incidents, a book series based on events at the Harvard Graduate School of Design. Designed by ELLA.

References: Curbed article on Jordan: https://ny.curbed.com/2018/1/10/16868494/harlem-history-buckminster-fuller-development-rezoning

New Yorker article on Skyrise for Harlem: https://www.newyorker.com/culture/culture-desk/when-june-jordan-and-buckminster-fuller-tried-to-redesign-harlem

Thinking about Utopias and Wakanda with references: https://www.architecturaldigest.com/video/watch/the-blueprint-show-expert-breaks-down-wakandas-architecture-in-black-panther

MARC NORMAN (“Lit Review: A Rage in Harlem: June Jordan and Architecture”) is the Larry & Klara Silverstein Chair in Real Estate Development & Investment and associate dean of the Schack Institute of Real Estate at NYU. He founded the consulting firm Ideas and Action, and has over 25 years of experience in community development and finance. Currently, Norman consults with organizations throughout the U.S. and the world on issues related to the built environment.