As a Sri-Lankan American who is both teaching and practicing in the field of architecture, I have been abundantly exposed to how the profession neglects global issues that we have the capacity to help solve. Our social and economic infrastructure and educational system in the U.S. provide us the ability to help facilitate solutions for those who don’t have access to the same tools we have. I am grateful for the opportunity to have made it far enough to actually enter the field: In 2020, approximately 22% of architects in the United States identified as a racial or ethnic minority, according to data from NCARB’s Record holders. Practicing architecture is a privilege that most minorities don’t enjoy because of the constant uphill battle, but I always wonder how we can do more.

Take Sri Lanka as an example: There, climate change is a daily reality, and its effects are felt deeply and devastatingly. In recent years, the island nation has witnessed an alarming increase in the frequency and severity of floods and droughts. These natural disasters have left a trail of destruction, affecting millions. Communities are uprooted, agricultural lands are inundated, and critical infrastructures like roads and schools are devastated. This repetitive cycle of flooding creates a perpetual state of instability, undermining the country’s efforts to address hunger and economic challenges. Known for its rich cultural heritage and natural beauty, Sri Lanka now faces a crisis that poses not only environmental challenges, but also exacerbates hunger, economic instability, and political turmoil.

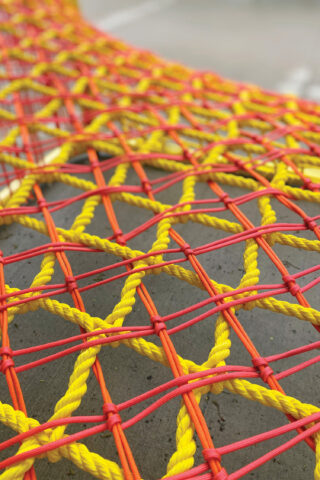

In the face of this escalating crisis, architecture and urban planning emerge as powerful tools. The right architectural strategies can significantly mitigate the impacts of flooding. Concepts like building on stilts, using flood-resistant materials, and designing flexible public spaces that can withstand water surges not only ensure safety, but also preserve the continuity of daily life during and after floods.

Though challenges abound, there are glimmers of hope. For instance, some Sri Lankan communities have started adopting elevated houses and community centers, which remain functional even during severe floods. These practical solutions, rooted in traditional knowledge and enhanced by modern technology, demonstrate the potential for architecture to offer tangible relief in crisis situations.

Implementing these solutions on a wider scale in Sri Lanka requires overcoming significant hurdles, including limited funding, bureaucratic complexities, and the need for community buy-in. Yet, these challenges also open doors for innovative thinking, international collaboration, and the empowerment of local communities to take charge of their built environment. This situation calls for a collective response from architects, urban planners, policymakers, and, crucially, the communities themselves. There is a pressing need for designs that are not only environmentally resilient, but also culturally sensitive and economically feasible. The architectural community, especially those with ties to these countries in peril, must rise to this challenge, bringing diverse perspectives and innovative solutions to the table.

The crisis in Sri Lanka serves as a stark reminder of the broader implications of climate change and the vital role architecture can play in addressing them. As the world grapples with these unprecedented challenges, the need for resilient, sustainable, and inclusive architectural solutions has never been more urgent. It’s time for the global architectural community to come together and turn these challenges into opportunities for building a more resilient future.

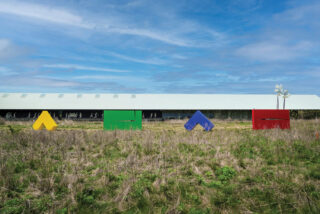

Often, the strategies we are able to experiment with, and create prototypes of, in the United States can easily be deployed in countries that are facing urgent situations. I can only hope that our focus can shift from how advanced technology can generate “eye-candy” geometries, as architectural spectacle, to how it can contribute to designs that are adaptable and deployable in various countries dealing with issues of climate change.

The architecture, engineering, and construction industries are responsible for over 40% of global energy-related carbon dioxide emissions. As architects and designers, we speak of how we are acting as climate warriors, yet we continue to build with massive amounts of concrete and steel. The profession agrees that we are meant to be problem-solvers and catalysts of change, so we must put our energy into being aware of the world’s most vulnerable communities and working to help them. Effective solutions require collaborative and interdisciplinary approaches. We cannot achieve meaningful progress alone.

Randy Fernando, Assoc. AIA, is an adjunct instructor in the department of architecture at the University at Buffalo School of Architecture & Planning, a lecturer at Buffalo State University, and creative director of MOV.E, a design research practice focused on collaborative community initiatives. Fernando co-teaches UB’s study abroad program in Costa Rica, a nine-week program that concentrates on tangible community service and climate resilience research.