The School Construction Authority (SCA) maintains 1,400 public school buildings serving more than one million students in the five boroughs of New York City. It analyzes the flow of students into multitudes of neighborhood and borough-wide schools, and it repairs, expands, and builds new structures—quickly—as demand changes. Currently, the SCA anticipates needing more than 6,200 new seats in Queens high schools alone by 2026. Its budget, fortunately, is appropriately enormous: $2.13 billion for 29 extensions and new buildings in Queens, adding more than 18,000 seats, and $19.4 billion to manage the herculean task of building and maintaining schools citywide from 2020 to 2024.

Thus, on a busy section of Northern Boulevard at the crossroads of Woodside, Astoria, Sunnyside Gardens, and Jackson Heights, between the Home Depot and a row of car dealerships, a new $178.85 million high school designed and built by SCA’s in-house staff of 170 architects and engineers is expected to serve more than 3,079 teenagers. It’s the biggest project in the SCA’s history, and its bylaws dictate that 40% of the scoping, design, and construction support work be done in-house, with the rest contracted to consultants. “They go to the in-house staff because they know we can handle challenging projects that are tight in construction schedule,” says Jahae Koo, director of the SCA’s architecture and engineering department.

At the moment, the Northern Boulevard structure is raw. So far, its fire-retardant-coated six-story steel shell has pre-cast concrete panels on a few sides, which will mitigate the sound from the busy four-lane road and Amtrak trains running behind and achieve an extremely high level of energy performance. Flatbed trucks roll up with more of the panels embedded with four-inch rigid insulation, which crews lift on cranes and attach to the structure. This school must open by September 2025, but it doesn’t yet have a principal, teachers, staff—or walls. “Understand, this has been going on for months!” shouts a construction manager behind a closed door, as we meet in the construction office trailers parked on the building site.

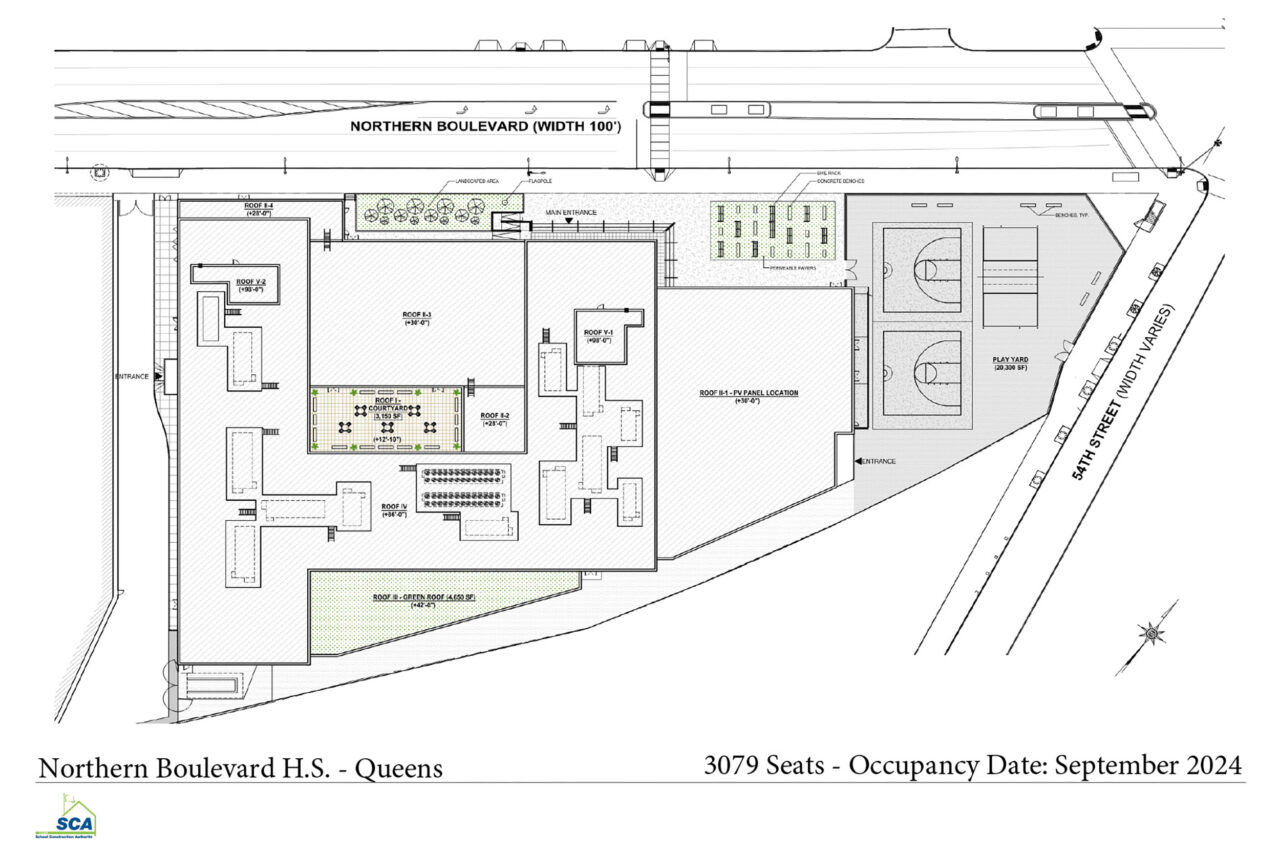

Because of the accelerated schedule, the project had to be conceived, designed, and built based on the SCA’s tried-and-true ideas of spatial organization and understanding of how to incorporate flexibility for the school’s future administrators. The structure will accommodate 96 classrooms, including six art rooms, three music rooms, and six science labs, along with three exercise rooms, a two-story competition-size gym, changing rooms and showers, two cafeterias, a 550-seat auditorium, bike storage, and outdoor handball and basketball courts. Fifteen special education classrooms will be contained in their own school within the same building—there will be multiple principals running several distinct schools with their own administrative offices within groups of floors in the two wings of the structure. The special education classrooms will have bathrooms and a dedicated second-floor courtyard open to the sky, offering students a place to play and find calm within the commotion of a high school the combined size of three city schools.

“That’s one of the challenges: How do you design a high school community for such a large number and still have an impact?” asks Koo. “It’s important that our building façade design embraces and opens to the community.” The scalloped entry plaza sits back from the street to create open space for play areas and socializing. Two six-story wings on either side of the entrance can be subdivided and administered by multiple principals to manage the huge population. The large number of science labs at upper levels anticipates the educational interests of young people who were still in elementary school when architects developed the program.

In terms of sourcing of materials, energy efficiency, building envelope, water conservation, and storage of stormwater, the Northern Boulevard building meets the latest updated codes. Its R40 roof and R25 walls, energy use index of 28, 270 rooftop solar panels, plumbing that uses 35% less water than normal fixtures, and regional sourcing of steel and pre-cast panels meet the SCA equivalent of LEED standards. All city school buildings now undergo a blower test for air tightness. Rainwater is collected in detention tanks below the plaza area.

Nevertheless, time is of the essence on school projects, and with construction costs doubling in recent years, efficiency applies to building methods as much as to systems and materials, says Peter Bafitis of RKTB, a longstanding design consultant for NYC public school projects. “It’s sort of like Broadway—the show must go on,” says Bafitis. “It’s like that with public schools. The buildings need to open in September. So time is money, and reducing the construction time is really important.”

Pre-cast concrete panels like the ones used in the Northern Boulevard High School are one way to speed up construction. By cutting out masonry and inserting insulation within the concrete, the panels eliminate at least two trades, shortening time on-site and reducing costs.

Rain screen systems are also being tested on a few new RKTB projects. These include PS 116 in Jamaica, Queens, whose permits have just been filed, and PS 730K, a $63 million school for 325 students in grades three to five in Sunset Park, Brooklyn, set to open in September. The rain screens have a waterproof membrane facing the interior, with a panel system outside that allows water to drain within the wall system, which is then clad on the exterior with stone, terra cotta, or fiber cement, saving time and money and also cutting out multiple installation trades.

RKTB’s recent projects for the SCA predominantly fall within a typology that is far more common than the newly constructed Northern Boulevard project: additions to existing school buildings. Two years ago, RKTB added 200 K–8 seats to PS 19, a 1924 school building in the Bronx’s Woodlawn Heights, shifting the entrance to a more open space and inserting an enclosed gymnasium, a modern administrative suite, and a “cafetorium”—a combined cafeteria and auditorium. “In a way, it’s more challenging to do a school addition, because you have constraints involved,” Bafitis says. “You have structural, logistical constraints, but also aesthetic considerations: how to blend in, how to be contextual, how to connect to a building with an older vocabulary. So we’re always balancing that with our work.”

For a $50 million addition to nearby PS 87, a K–5 elementary school in the Wakefield section of the Bronx, RKTB carved a courtyard into the school’s playground, extending its brick façade to accommodate 400 students by this fall. Eight new first- to fifth-grade classrooms, classrooms for students with disabilities, art and music rooms, and suites for administration, guidance, and medical services are topped by a gym—twice the size of the existing building—that doubles as an auditorium. “The gym is never just a gym in New York City,” Bafitis says. “Space is at a premium. Gyms are often combined with other functions.”

Besides providing classrooms and social spaces that shape formative early memories of childhood, the schools themselves perform an invaluable civic function for communities. All NYC schools include public art commissioned to nourish a sense of place, such as PS 19’s inspirational graphics contain-ing quotes from Miles Davis, Duke Ellington, and other jazz stars interred at nearby Woodlawn Cemetery. Voting, community meetings, basketball tournaments, fundraising drives, performances, and other local initiatives often take place within their combination gym/auditoriums. Their play areas often become multiuse gathering spots and sports venues after school is out. Ultimately, the design of a school is a community-building project par excellence: Its design, environmental quality, and public spaces reflect the values of a place, just as the school’s pedagogy is instrumental in creating citizens with shared knowledge, references, and skills to advance their needs and interests.

“One thing you realize about school design in New York—and almost any city—is just how much it means to a neighborhood,” Bafitis says. “A school is a very important civic building, a pivotal place, in the life of any neighborhood. School design is community-building at its core.”

STEPHEN ZACKS is an advocacy journalist, architecture critic, urbanist, and project organizer based in New York City. A graduate of Michigan State University and New School for Social Research with a bachelor’s degree in interdisciplinary humanities and a master’s in liberal studies, he serves as president of Amplifier Inc., a nongovernmental organization imagining the future of planetary governance.