The landscape architecture studio MNLA has been responsible for several prominent landscape interventions around the city: Its work at Pier 42 transformed a former parking lot and industrial pier into a new park for the Lower East Side, and the firm’s collaboration with Heatherwick Studio on Little Island created a new destination on Manhattan’s West Side. The studio has also led the design of plenty of less visible but equally thoughtful efforts, such as the Hudson Street reconstruction and Bogardus Plaza in Tribeca. One of its most recent efforts, Plaza 33, is also making a significant difference for pedestrians in navigating a knot of congestion and crowds near Madison Square Garden.

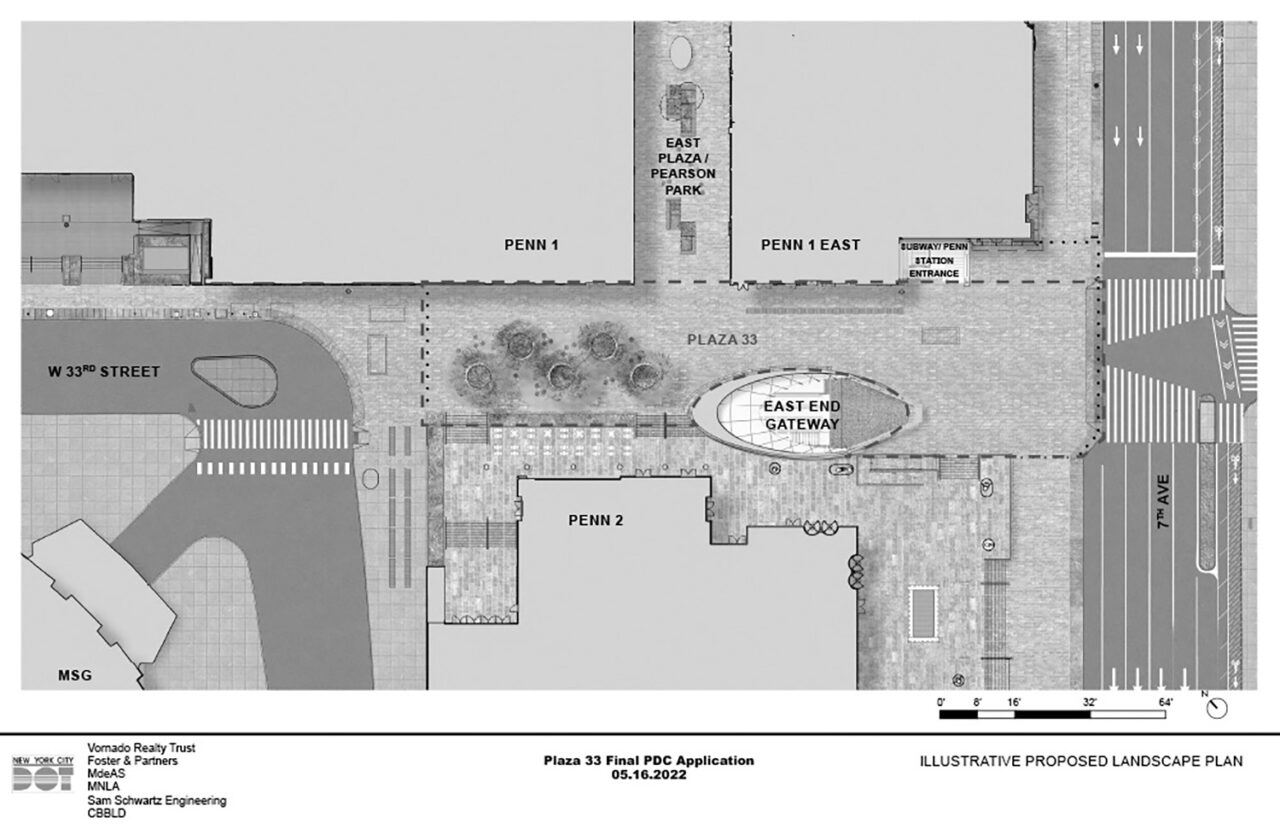

The space, a half block of 33rd Street just west of Seventh Avenue, was first transformed into a temporary pedestrian area in the summer of 2015, with a W Architecture plan that brought terraced seating to the site. MNLA began additional work there in 2017, as a process of improving privately owned public spaces (POPS) around Penn Station, in real estate investment trust Vornado’s “Penn District.”The effort accompanied a variety of improvements, most noticeably MDeAS’s recladding-plus-cantilever-plinth addition of 2 Penn Plaza. Some elements of these projected redevelopments remain up in the air, but Plaza 33 is very much a fact on the ground, bustling today.

MNLA dealt with more practical challenges on this site than on most. Founding Principal Signe Nielsen explains, “This plaza is unlike any other plaza in New York City in that it is a primary access point to the busiest train station in the United States.” This wasn’t the only complication of the design brief, however. A new entrance to the Long Island Railroad was added to the eastern end of the block in 2020. Thirty-Third Street remains open to vehicle traffic on the western half of the block, providing trucks access to Madison Square Garden’s loading docks. A lane of the plan also had to remain open for emergency vehicle use—and to accommodate droves of commuters on foot. An average of 8,000 people per hour use the block’s new LIRR entrance. All of this was literally built on top of the train station, requiring the designers to work within a maximum of three feet and a minimum of five inches clearance before hitting Penn Station’s subterranean roof.

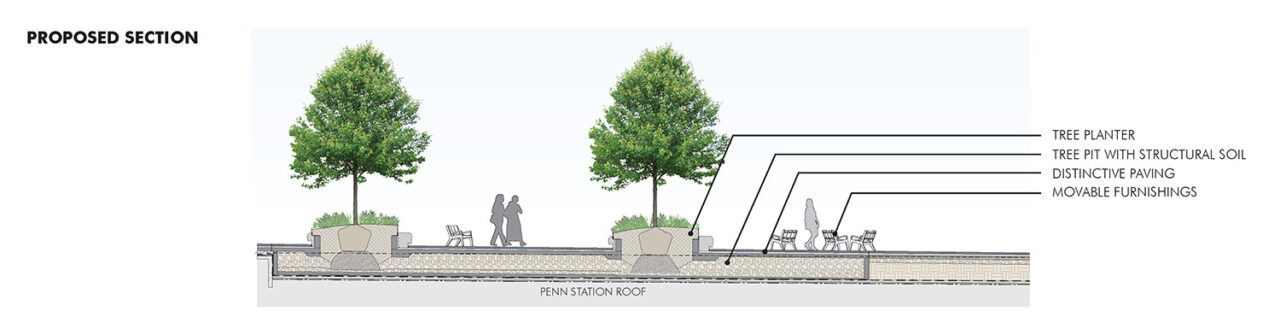

Working deftly within these constraints, MNLA managed to place five red maple trees along the south side of the site, each surrounded by irregularly curved marble fixtures that are half-bench, half-planter. These are topped by stainless-steel rings, providing an adequate cradle of soil—akin to olives atop a submerged sandwich. Melissa How, senior associate at MNLA, says the structural soil for the trees rests on a concrete subbase layer, a setting bed of the pavers, and then the pavers themselves.

Nielsen elaborates on the choice of rounded planters. “We’d talked about a lot of different ideas during the course of the project,” she says, “but the main ideas are about maintaining circulation space, not unnecessarily cluttering the plaza, and making it a welcome space for people to pause during their daily commute. We eventually settled on the rounds because that seemed the friendliest and most democratic way of using the space.”

The soil stretches for 1,000 cubic feet for four of the trees. In spite of their space-maximizing plans, the landscape architects chose October Glory maples, with small root balls, to fit into these tight spaces.

The designers also employed paving as another way to animate the site. For durability and character, Vornado selected six-inch-square cobble pavers made of Belgian petit granit, used widely in European public spaces. The aggregate includes traces of fossilized aquatic life, and the paving is laid in concentric “cloud” patterns. “It is also very evocative of the historic bluestone you see in other neighborhoods in New York,” says How.

The planter-benches are carved out of Georgia Pearl gray marble, chosen for its veining and smooth texture well-suited for seating. Their irregular form has both aesthetic and practical inspirations. “The asymmetry feels very nice; it lends a little bit of dynamism to the plaza,” says How. “The round shape works very well with all the orthogonal buildings around.”The designers also planned for shade to be accessible to those who weren’t seated on the benches by using movable chairs on the plaza. “We want people to have the same experience of being under the trees even if they’re unable to sit on the bench,” she says. “So by not ringing the entire thing with seating, we allow people to pull up chairs underneath the trees.”

The maples were chosen for their varying seasonal shades of red. “We wanted the red to offset the very gray and stainless-steel look of the buildings around it,” says How. The trees will retain a relative formality, Nielsen explains, suiting the dignity of an urban plaza, and are expected to reach a height of 40 feet or so. “What I am most pleased to see,” she says, “is that even though it’s just five trees, their placement is such that it creates a special environment. It’s not a lot of random, scattered trees—they come together to create a total.”

What’s also notable is what isn’t there—namely, streetlights. The site is largely lit by spotlights on nearby buildings. This “moonlighting” strategy was designed to keep the plaza free of light poles that would obstruct pedestrian and emergency vehicular circulation. The elimination of light poles also allows for fewer constraints on the locations of movable furnishings for temporary events and activations. As the plaza already has a lot of ambient light from the adjacent buildings and the illuminated signage of the district, lighting within the plaza is intentionally designed to provide subtle downward illumination that will not blind visitors or contribute to light pollution. The moonlighting is accented by tree up-lighting and additional lighting at the base of the tree planters.

A testament to the project’s success has been its very considerable use. “People create the vibrancy—they are the vibrancy,” How explains. In a location defined by people rushing by, some are now able to sit down for a while.