During June’s heatwave, we were suffering in a sweltering New York City. We walked the hard streets, drenched in our own sweat, trying to visit the green roofs on the city’s public schools. Up there, gentle breezes passed by, while trees, pavilions, and canopies absorbed heat from the radiating sun. Heat waves, so stifling from below, are not as oppressive on a green roof. This palpable difference demonstrates what everyone knows on paper: that green roofs unquestionably improve the livability of cities. And yet, looking out from my office at the desaturated paint and tar of surrounding roofs, green is largely absent. It is a failure of New York’s infrastructure policy that, despite widespread desire and support, there are still so few green roofs. We can’t help but wonder: Where are they?

In the early 2000s, green roofs gained traction as a type of sustainable infra- structure for cities. The traditional design of an infrastructural green roof is a wide, flat, planted roof area, constructed with a waterproofed membrane, a root barrier, drainage, soil, and plants on top. Further complicating implementation, many rooftops don’t adhere to a standardized format, making standardized designs impossible. And even though cities like New York understand the benefits of green roofs, and the city government strongly supports their installation with funding and regulations, there are still only 736 green roofs among the city’s one million buildings, which amounts to only 0.07% application overall.

To understand the underlying cause of this critical absence, my firm, Studio Link-Arc, is studying green roofs on New York City public and private schools. My colleagues and I have visited a quarter of them, and have already noticed unexpected patterns, leading us to believe that the practical application of green roofs is not well understood.

For schools that have managed to implement a green roof, the projects have been wildly successful. Each school’s spaces deviate from the traditional infrastructural style, incorporating educational spaces, rooftop classrooms, agricultural spaces, climate observation stations, performance spaces, laboratory gardens, and countless other areas. Their designs vary wildly, reflecting both the social identity of the schools and the broader architectural trends in New York City.

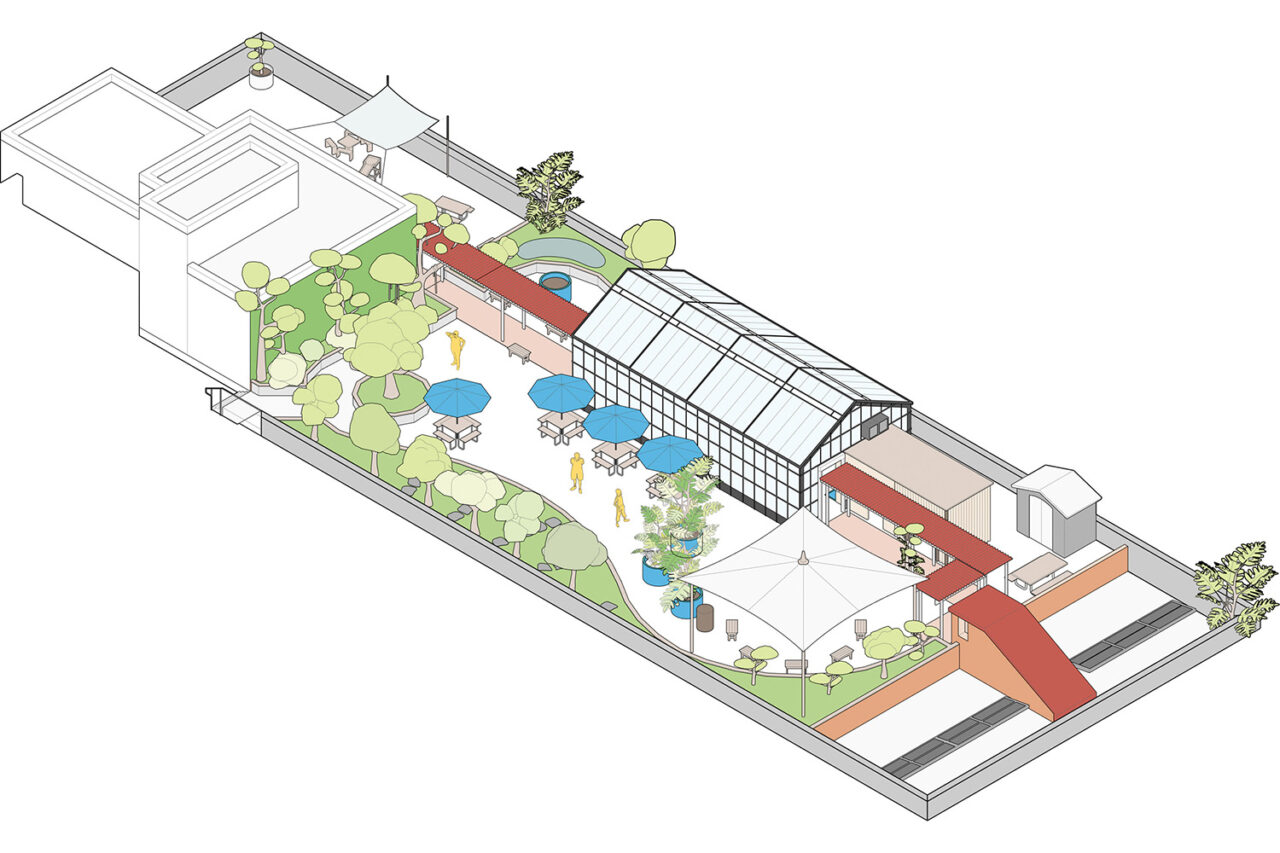

A few milestone examples from our study show the wide range of practical applications. For instance, Ballet Tech in the Flatiron District features a 15,000-square-foot, drought-resistant green roof installed as part of a renovation. Although it is non-occupiable for students, it hosts beehives managed by a local beekeeper, and the honey produced is sold around the city. In Upper Manhattan, P.S. 6 Lillian Blake School provides another model; its roof includes a greenhouse classroom, a small orchard, and a green wall habitat. The planted spaces are in sculpted raised beds as op- posed to being spread evenly across the total roof surface. By spatially prioritizing these design components over infrastructural ones, the design supports hands-on environmental and urban agricultural education. Meanwhile, P.S. 41 in the West Village combines infrastructural, educational, and environmental elements, creating a space where students can engage in scientific studies and complex ecological interactions.

School green roofs are unpredictable and idiosyncratic, the natural product of an imperfect system. Although New York’s school green roofs generally fulfill their promises, their deployment is uneven, often concentrated in affluent areas where municipal infrastructure faces fewer stressors.

School green roofs illustrate broader policy issues affecting sustainable development in New York. The city has supported the application of green roofs largely through funding and grants, but building codes, practical concerns, and public policy all play a role. Throughout the city, the government has defined priority community districts (PCDs), zones that suffer from high heat and storm surges, making them high-impact zones for green roofs. But, in practice, sustainable infrastructure continues to be applied not in PCDs, but in affluent and stable ones. The reasons for this are myriad, but the most critical are improper allocation of funds, practicality limitations, and limited legislation.

First, financial opportunities are avail- able but remain largely untapped, and targeted funding has not led to increased build-outs in PCDs. The city’s tax abatement program allows building owners to be reimbursed for some or all of the costs when replacing a traditional roof with a green one. While this program has significant potential to make strategic applications more equitable, it does not address all the ways that money limits ac- cess. An engineering study to determine the mere feasibility of establishing a green roof can cost around $50,000. For public schools, which face budget cuts citywide, this study often takes a backseat to more pressing needs like upgrading ventilation systems, repairing deteriorating façades, and updating classrooms.

Second, practical issues also contribute to the limited number of green roofs. For anything beyond a basic sedum roof, maintenance becomes costly and challenging, often deterring administrations from moving forward with such projects. Water management remains a significant concern for the viability of these roofs. Among the few schools we visited so far, at least four have experienced serious water management problems. Of these, three schools have closed their green roofs, and one is in the process of completely replacing theirs.

Finally, new legislation could support green roof installation, but early adoption has been underwhelming. Local Law 97 mandates either solar panels or a green roof on new construction. However, most new projects are opting for solar panels due to their relative simplicity. Additionally, Local Law 97 does not address sustainable infrastructure for existing buildings, which constitute the vast majority of New York’s built environment. Representative Nydia M. Velázquez (D-NY) has repeatedly championed the Public School Green Rooftop Program Act, which would use federal funds to prioritize green roof applications on primary and secondary schools. This is not the first time this measure has been proposed, but it looks more promising.

Our research underscores the need for a more integrated approach to green roof installation. We would like to see city departments leading by example, using publicly owned buildings to promote green roofs. Addressing policy gaps and ensuring equitable application across different types of schools will be essential for increasing the number of green roofs in New York City. As we move forward, it is crucial to balance new regulations with the needs of existing structures and address the disparities to improve city life through green roof design.