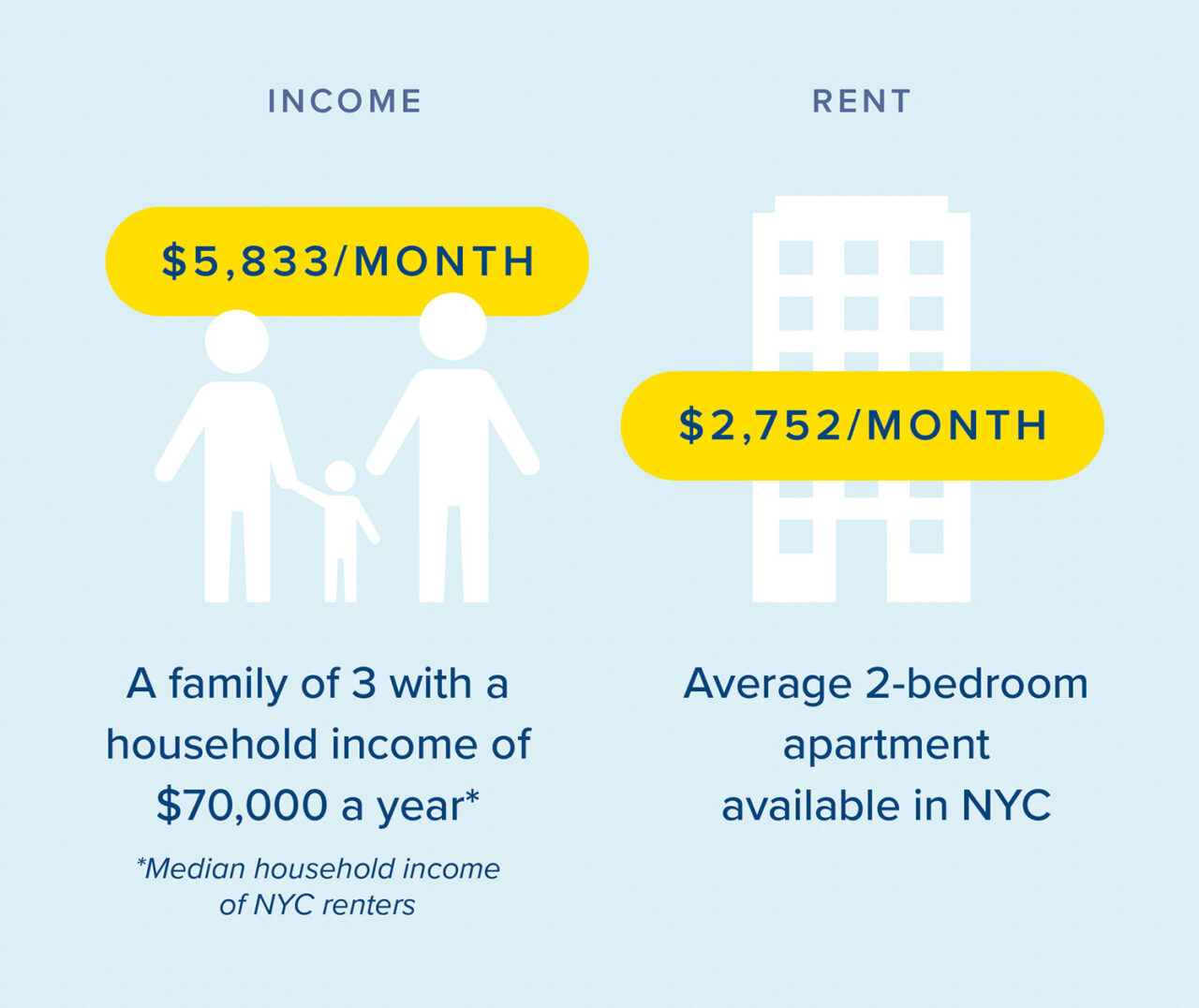

With more than half of its residents currently rent-burdened, a net vacancy rate of 1.4% (below 1% for rent-stabilized units), and the power balance between tenants and landlords grievously askew, New York City needs a sharp increase in its housing stock. Every mayoral administration for decades has recognized the problem. None, to date, has solved it.

In September 2023, Mayor Eric Adams unveiled City of Yes for Housing Opportunity, a proposed amendment to the city’s 1961 zoning code that strives to create “a little more housing in every neighborhood” by strategically adjusting regulations that have impeded construction. In late September, the City Planning Commission voted to approve the proposal. The City Council Subcommittee on Zoning and Franchises will hold a two-day hearing on October 21 and 22, followed by a final City Council vote before the end of the year. The plan will shape citywide housing policy in ways that extend beyond the current administration. It’s an outcome that proponents are not taking for granted.

The housing component is one of three City of Yes initiatives that Adams first made public in June 2022, alongside initiatives promoting carbon neutrality and economic opportunity. Details have been under public review since April 2024, but a website, created by FXCollaborative, illustrates the different measures affecting low-density districts, medium- and high-density districts, and the city at large. (FXCollaborative also provided zoning and strategy recommendations, as well as graphic and digital design for the proposal.)

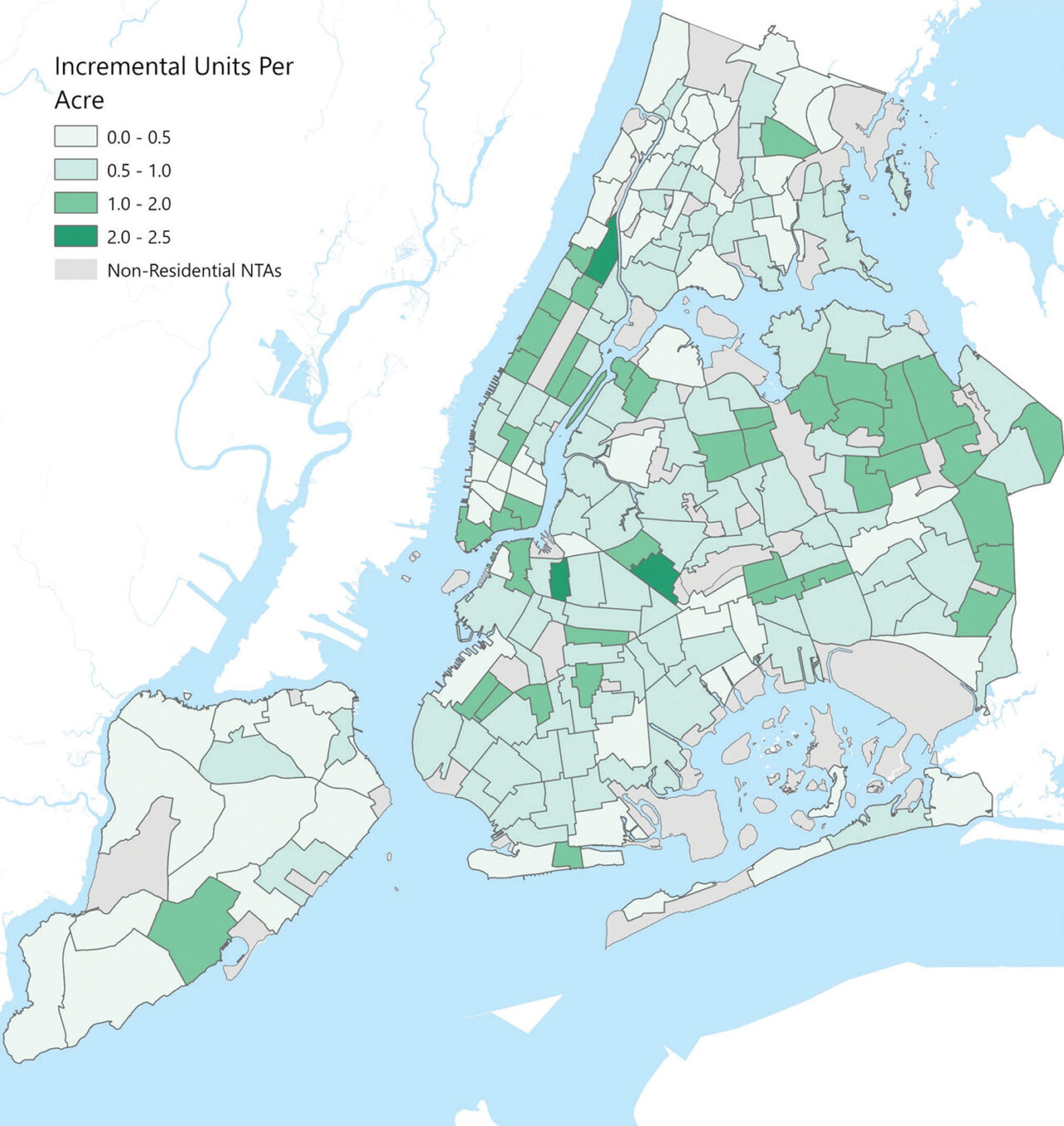

“We have an unequal geography of housing production,” says planner Veronica Brown of the Housing Division at the Department of City Planning (DCP). “Only a few areas are producing a lot of housing, while some produce none.” Brown believes the plan of action proposed in City of Yes will introduce incremental growth in housing options for New Yorkers who need it most.

Perhaps by signaling that its measures will be a decisive victory for YIMBYs over NIMBYs, City of Yes has attracted energetic support, with favorable statements by the Regional Plan Association, the New York Housing Conference, and (more provisionally) the Citizens Housing Planning Council and the Municipal Arts Society. It has also inspired vehement opposition. Though four borough presidents (all but Staten Island’s) have recommended the measure, over half the city’s 59 community boards have voted against it, and of the 17 favorable votes to date, only two were unconditional. (The counts may change after press time: City Limits, the non-profit news organization, maintains an interactive map tracking the boards’ positions, with links to their recommendation letters.) Commentators in assorted media outlets have assailed City of Yes as a disrupter of low-density neighborhoods and a boon to developers, with no guarantees that the public will benefit from it. On the other hand, some supporters, like Peter Bafitis, AIA, managing principal at RKTB Architects and former co-chair of AIA New York’s Housing Committee, applaud the proposal’s goals and strategies and believe “it should have gone farther.”

Rosanne Haggerty, founder of Common Ground and Community Solutions, comments that “City of Yes is impressively pragmatic. It has a smart focus on housing forms and density levels that reinforce the existing, diverse physical and household character of NYC neighborhoods. And the proposals are well communicated, with sensitivity to the questions likely to be encountered in the public process.”

AIANY’s Housing Committee, citing the zoning amendment’s embrace of ideas that the Chapter has long promoted, expressed its support in a letter to City Planning Commission Chair Dan Garodnick in October 2023. Members of the committee acknowledge that City of Yes does not satisfy all parties on all issues, but welcome adjustments to details. David West, FAIA, a founding partner at Hill West Architects, Housing Committee member, and zoning specialist who has studied the details of City of Yes for the zoning and design committee of the Real Estate Board of New York, finds “a lot of good stuff in here, particularly in the medium-density zones. There’s almost nothing not to like.”

The treatment of high-density (R10) zones, West says, has caused concern for developers and some members of the AIA and the Citizens Housing Planning Council. Projects in those zones have relied on off-site inclusionary-housing certificates, which City of Yes replaces with “one-to-one ratio of affordable to market-rate housing, whereas the current voluntary inclusionary-housing program gives you three-and-a-half market to one affordable,” West explains. “At one-to-one, it’s not going to be economical to produce those certificates.”The sunsetting of existing certificates not only affects the real estate industry’s interests, but “also is a problem for the not-for-profits that have generated a lot of these certificates.” Still, he says, the proposed mechanisms encouraging transit-oriented development and conversions, allowing ADUs, and removing costly parking mandates add up to a favorable package. (Fears expressed in some low-density, transit-desert areas that City of Yes would ban parking construction are misplaced, West says. Where local market demand supports parking, “you’ll still be allowed to put as much parking in the building as you can today. However, it’s just not required.”)

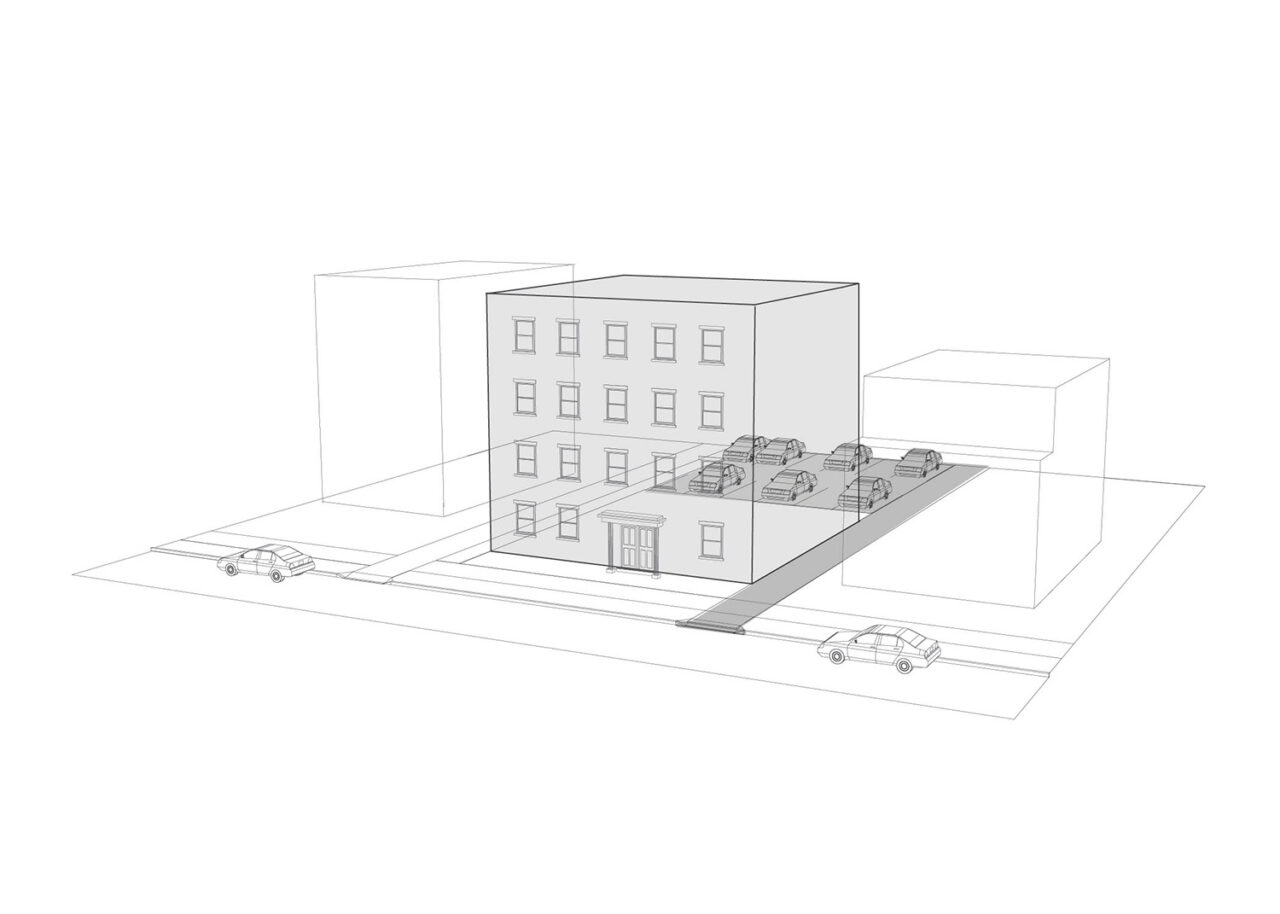

The zoning amendment’s so-called campus-infill provisions, West continues, improve on the 1961 code’s height-factor zoning, which encourages tower-in-a-park models and makes it difficult to free up leftover air rights, or floor area ratio (FAR), from uses such as parking lots “spread around in between buildings in ways that don’t really benefit the public.” As the New York City Housing Authority has unsuccessfully tried to do on some of its sites, West and colleagues once managed to add residential space at Columbus Square on the Park West Village superblock in the Upper West ’90s. “We channeled the floor area onto a parking lot that was no longer required to be left as a low-rise place,” he recalls, “and by hook and by crook, we manipulated the height-factor calculations to squeak out one big building there. But there are large areas of that site left unbuilt, and we’ve studied it for decades. How do we add something there that was almost impossible under the current zoning, mainly because of the height-factor rules? Under City of Yes, we would be able to add a couple of good-sized buildings on that site. We’ve looked at several of these sites and, invariably, the City of Yes infill provisions work 100 times better than the current zoning.” West summarizes, “I don’t know of a single site where we have people saying, ‘I wish City of Yes wouldn’t pass and we would be able to build under the old rules.’”

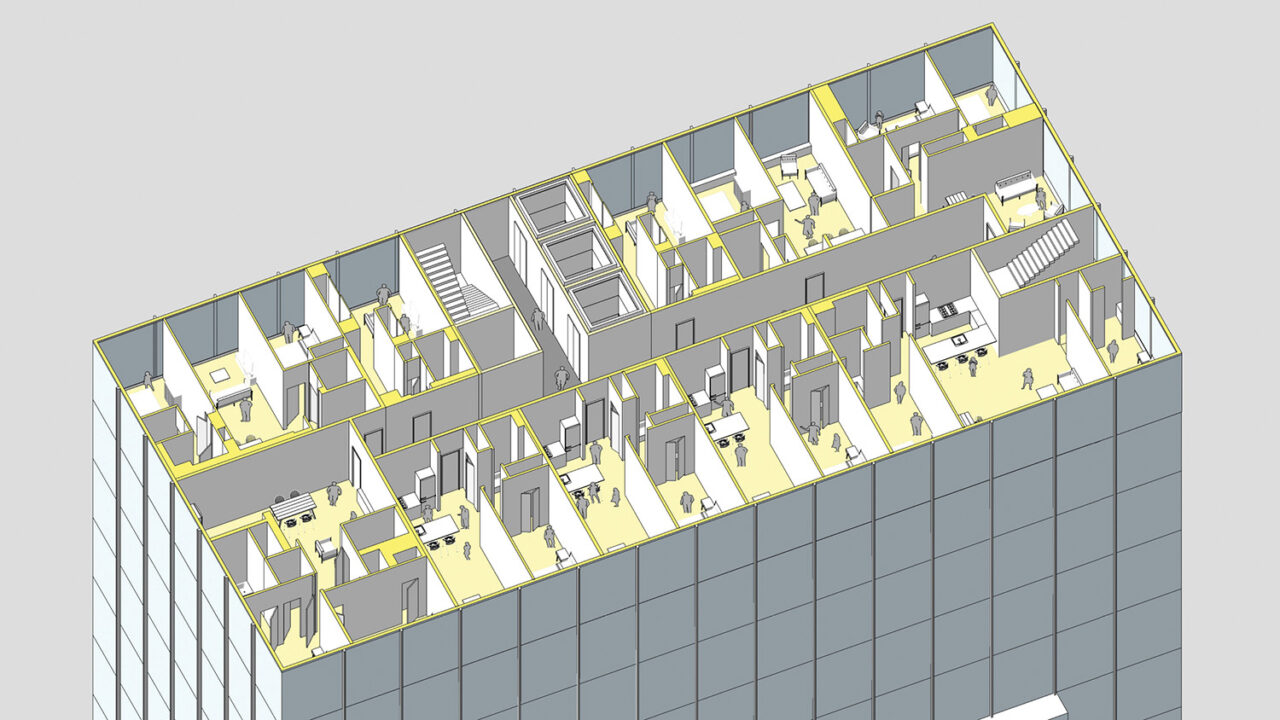

Bafitis points out several ways City of Yes corrects anachronisms in the 1961 zoning code, adopted “at a time when the car was king, and zoning was centered around car-oriented development.” Comparing the 1961 zoning to “death by a thousand cuts”and calling for its overhaul, he sees City of Yes as providing a long-needed “thousand Band-Aids.” It promotes transit-oriented development, expands the city’s Department of Housing Preservation and Development’s Affordable Independent Residences for Seniors increment (allowing affordable senior housing to be about 20% larger than other types) to any affordable housing, and allows conversions of office space, garages, and other underused structures that would be more beneficial as residences. Commercial conversion, he finds, is a promising enough trend that “the zoning should have gone farther to create some real bonus incentives” for that as well.

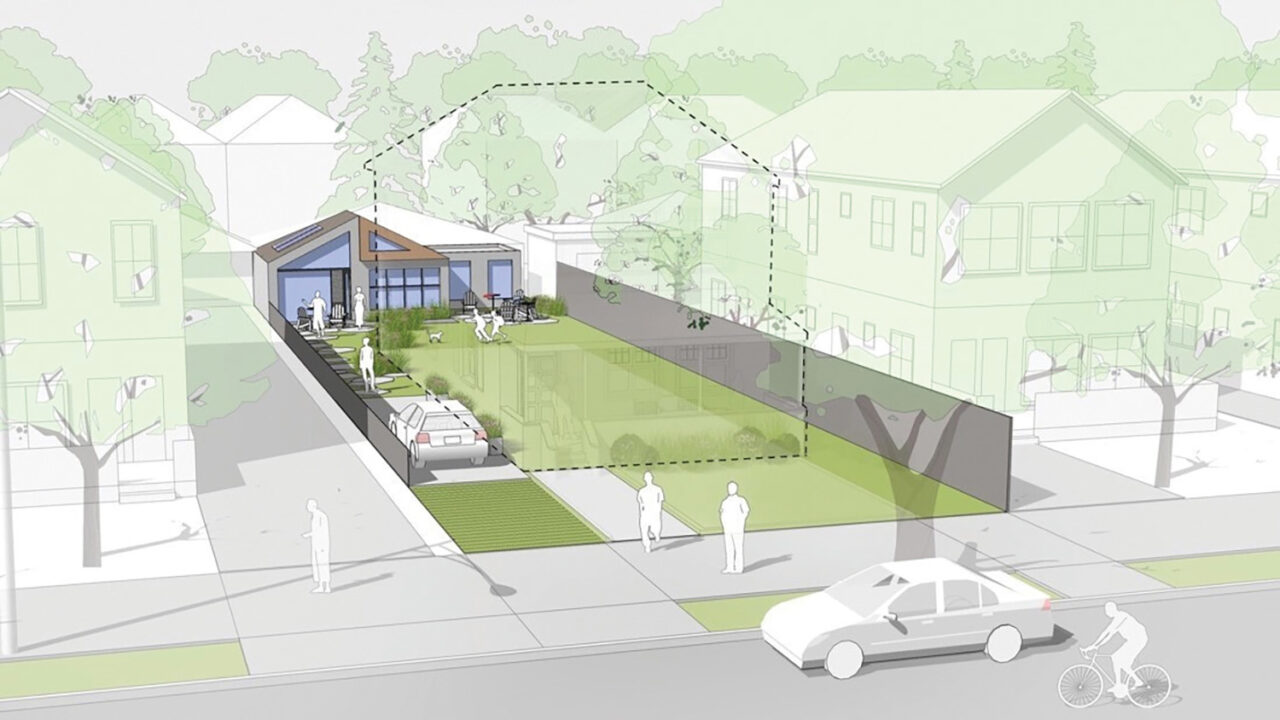

Another Housing Committee member, Darrick Borowski, AIA, principal at ARExA and professor at the School of Visual Arts, worked on an AIANY subcommittee exploring certain City of Yes provisions, “taking it out for a test drive on empty, city-owned lots within districts of council members who might be interested in understanding the plan, be open to it, be facing resistance, or be resistant themselves.” ARExA tackled ADUs; Magnusson Architects studied the plan’s Universal Affordability Preference (UAP), transit-oriented development, and Town Center components (see graphic above). From this exercise and the feedback from the electeds, Borowski says, “the new proposals we have tested out in specific sites and neighborhoods have not been terribly disruptive of the fabric of those neighborhoods.” Concerns from community boards over spatial effects, such as towers within a landmarked district, were not borne out; if anything, Borowski says, the changes were “underwhelming,” and the chief concern was how the program might reach its targets.

Local benefits, however, could be significant. At one test site in Jamaica, Queens, Borowski found that a change in mini- mum lot width in low-density zones under City of Yes made it possible to replace a house that had been torn down after the 1961 zoning (enacted after much of the neighborhood was built, and banning construction on lots below 40 feet wide). With this change, a small increase in FAR, and the option of an 800-square-foot ADU on the site, the lot could not only accommodate a rebuilt house, but could also include an income- generating component. “Having a rental in my house is why I can afford to live in New York,” he says. “For the middle class, that is an extremely powerful tool for staying in the city.”

While supporting City of Yes elements, Borowski finds that process-related critiques have some merit. “Communities feel like this is being dropped in their laps from on high,”he notes.“To an extent, I understand why they feel that way, because this has been happening in closed rooms.” Infrastructure to support densification in outlying regions of the city strikes him as a legitimate concern, but is “a planning conversation. I don’t know that it can be covered within a zoning proposal.” The proposal’s success, he notes, will also depend on concurrent work on related challenges: transit-oriented development and construction freed from parking requirements, for example, are both premised on reliable transit infrastructure, so that the potential benefits from both are inseparable from the problems of transit funding and congestion pricing.

Misperceptions of City of Yes goals have been widespread. For starters, it is not a radical rezoning. It does not rezone any district, but merely revises provisions applying to existing zones. Brown rejects claims that “this proposal is one-size-fits-all, is top-down, or is taking only one approach to every kind of neighborhood.” Different housing opportunities, she says, suit each zoning district, neighborhood, or density level, and “no single neighborhood is being asked to take it on alone.” Borowski has heard “a narrative going around that ‘we’re fundamentally changing the feel and character of my neighborhood.’” But, he says, “we’ve tested a bunch of sites, and we just don’t see it. The impacts are like 12 extra units here, five extra units here. In medium-density areas, the bump you get from UAP is a little bit higher. The changes we’ve seen are incremental and don’t feel like the end of small, low-density living in New York’s outer boroughs.” Bafitis points out that in the past, “new housing and development has been concentrated in places people don’t want it, in a lot of low-income communities, and none has been in wealthier communities.” City of Yes strives to distribute new housing evenly.“I like the egalitarian nature of this—the idea that we’re going to do it everywhere, even in rich neighborhoods.”

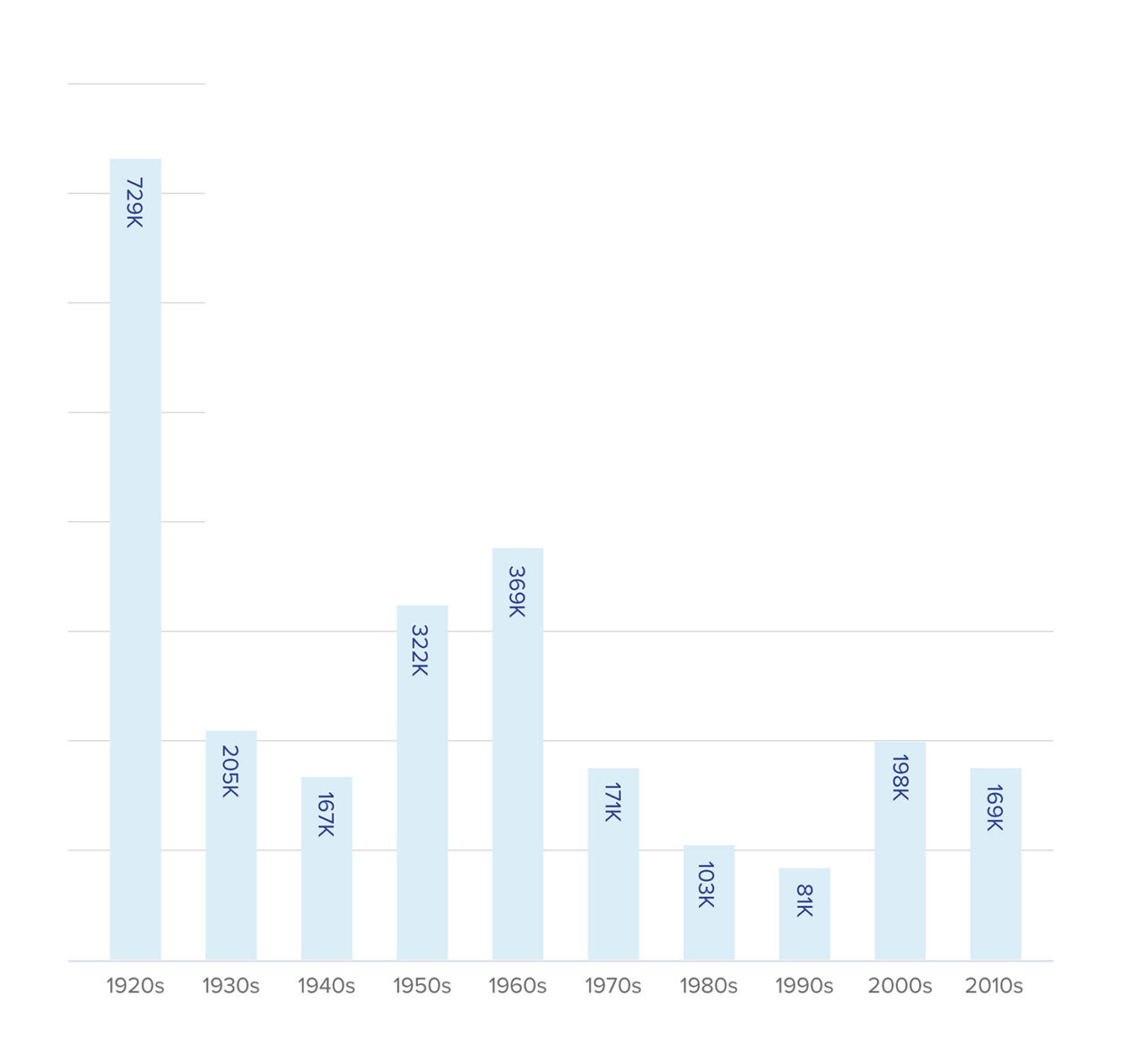

That the proposal encourages new affordable housing without mandating it strikes some observers as a positive feature, and some as a flaw. The Department of City Planning considered an affordability mandate in low-density areas, but decided the low development potential would most likely prevent any housing from being built at all. “We’re relying on private development and the market to produce affordable housing,” West notes. “That’s the tool we have at our disposal. We don’t have huge investments of federal dollars coming in, or even state dollars, as they had in the postwar era, when so much subsidized housing got built, and a lot of that was middle-income housing.” He sees some critics “look- ing for the zoning to solve larger societal problems. I don’t think that’s a realistic expectation.The zoning is just creating the box within which all these things can occur. But it’s got to be a good box. It’s got to be big enough. It’s got to make sense.”

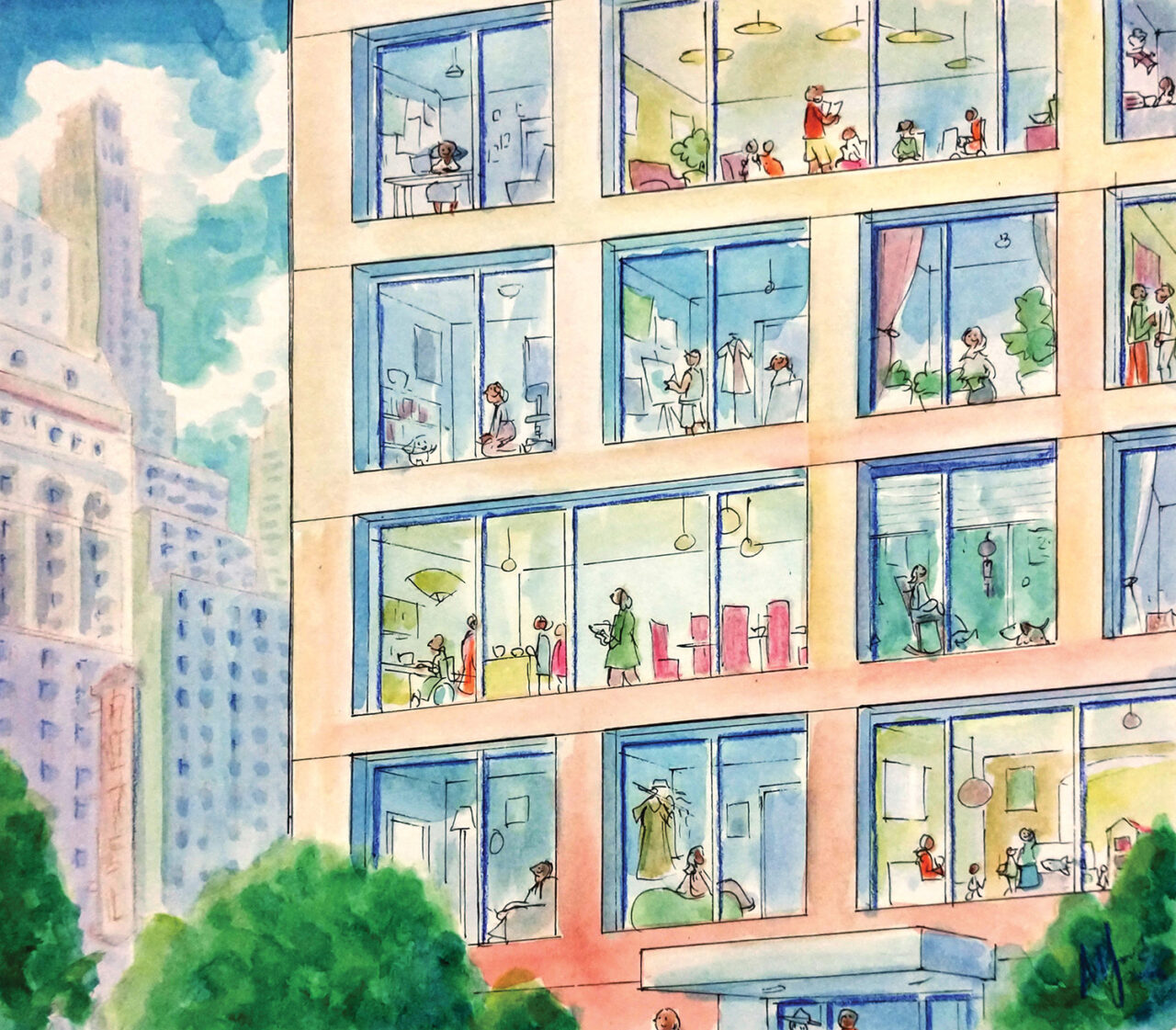

RKTB President Carmi Bee, FAIA, turns to 20th-century history for examples that made sense and strengthened communities. He recalls the Sunnyside Gardens plan by Clarence Stein and Henry Wright, with “Mom-and-pop apartments and duplexes, which became a model throughout Queens. You had a lower apartment, and the parents lived on top.”

By legalizing ADUs, City of Yes allows multigenerational spaces. “To me, the whole idea of keeping a family unit together is very important,” he continues. “This happens in multistory districts.” Citing an infill prototype that RKTB developed in 2004, a four-story walkup “meant to fill in vacant lots in medium-density districts,” Bee envisions its possible reintroduction under City of Yes as one of many options that could retain the middle class, “the backbone of a city. I remember when there were all these public programs to produce middle-income housing, and it was very simple: you needed a middle-income population to make a city whole.” If private development can’t accomplish this, Bafitis adds, “I think the state should be more proactive in providing housing, especially given the dimensions of the crisis we’re in now. What other entity can marshal the forces at a scale that’s necessary, except the state?”

City of Yes implies that New York has too long been a City of No, red-taped to the point that residential construction can’t come close to meeting the populace’s needs. By “re-legalizing housing types that have been banned by our current zoning,” Brown notes, including mixed-use buildings in low-density districts, and buildings with multiple exposures and a courtyard, a new regulatory atmosphere may foster progress against the city’s housing gap. The key question is, how much? Mayor Adams has conjectured that City of Yes would yield 100,000 new homes over the next 15 years, a step toward the “moonshot” goal of 500,000 homes in a decade. For context, a May 2024 McKinsey and Company report for the Regional Planning Association found a current region-wide shortage of 540,000 housing units, possibly rising to 920,000 units by 2035. Recognizing that zoning is one of many tools available, Brown notes that the city will continue pursuing the Department of Housing Preservation and Development affordability programs, state tax incentives, and other tenant protections.

“Zoning does not dictate exactly what will happen just because we have allowed things,” Brown says. “Zoning is a long game. Zoning alone isn’t going to be enough to solve the housing crisis.” City of Yes for Housing Opportunity may be a meliorist, roundabout approach to a problem that some believe re- quires fundamental changes—but it is a start.

BILL MILLARD (“City of Yes”) contributes regularly to Oculus, The Architect’s Newspaper, Metals in Construction, Annals of Emergency Medicine, and other publications.

His book The Vertical and Horizontal Americas, assisted by a Graham Foundation grant, moves glacially forward.