On May 13, 2022, New York Times architecture critic Michael Kimmelman delivered the keynote address at NYC’s Housing Crisis, a day-long conference organized by the Center for Architecture with support from the IDC Foundation. Supported additionally by academic partner NYU Schack Institute of Real Estate and media partner Architectural Record, the conference was held at the Stavros Niarchos Foundation Library, the newly renovated Midtown branch of New York Public Library. The text of the keynote follows.

I am so glad we are gathered here because, like you, I am extremely worried. I am worried because, with all the problems we face, and there are many, there is no bigger or more urgent crisis with greater ripple effects in New York today than the affordable housing shortage. And I also worry about the state of our participatory democracy. I worry we are losing the melody of our cosmopolis—forgetting what it takes to accomplish really big things together. It begins with getting different interested parties and public authorities together and having a robust, honest, constructive conversation.

New York has historically seized on crises and trans-formed them into opportunities. That has been our secret sauce—the source of our reputation as a great, forward-thinking metropolis of modernity and hope. We screw up—slum clearance, Hudson Yards—or we are screwed—9/11, COVID—and somehow we eventually stumble to a better place. It used to take months for a restaurant to get a permit from the city to do outdoor dining, and removing even a single parking space from the streets would trigger the Battle of the Somme from car owners. But city officials granted 10,000 permits and removed even more parking spaces overnight when COVID threatened to bankrupt the restaurant industry. Streateries have transformed neighborhoods, rich and poor, all across the city, reminding New Yorkers that our streets have not always looked the way they do; that they are not, in fact, the property of car owners but are public spaces; and that they can be reimagined and remade with remarkable speed when we have the will and imagination. That isn’t only true for outdoor dining.

In the 18th century, we poisoned the Collect Pond in Lower Manhattan, which was the main freshwater source for colonial and early American New Yorkers, leading to deadly outbreaks of cholera. And, in response, we established what is today the city’s largest bank to underwrite vast new sewer and water systems. These allowed for the creation of Central Park, the New York Public Library at 42nd Street, and much else whose architecture derived from the network of aqueducts and reservoirs we created to make up for our insane idea of putting tanneries next to our water supply. During the 20th century, with the collapse of the shipping business and the city’s industrial waterfront—New York’s lifeblood since Henry Hudson first set his eyes on the island of Mannahatta—we diversified our economy, cleaned up our air and water, and reimagined our coastlines. The housing crisis, it seems to me, is a similar, slow-evolving disaster.

When I moved back to New York from Europe a decade ago to start my job as the Times architecture critic, affordable housing was at the top of my list of issues to address because it clearly seemed the biggest problem in the city. The first thing I wrote about was an affordable housing project in the South Bronx, Via Verde. In highlighting that building, I wanted to make the point that design and architecture were part of the city’s housing crisis—but also part of any solution. I tried to weigh the building’s premium on high-end architecture against the number of additional apartments that might hypothetically have been built with that same money. How do we judge value versus cost? What is the value of dignity, pride, durability, and equity in the things we build? These are things architecture can bring to the affordable housing equation.

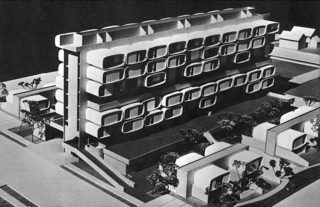

But architecture is not where this conversation needs to begin. And it is not where we are starting today. Architects can challenge us to think in new ways; they model a culture of collaboration, and they love cooking up fantasies of, say, turning New York’s inventory of small, odd, leftover lots of public land into affordable housing projects, whether or not the economics pencil out. Renderings can be inspiring. But the reality is that millions of rent-burdened New Yorkers today are spending a third to a half or more of their incomes on rent—and some are hot-bedding in Queens, where 11 people died during Hurricane Ida when their illegal basement apartments flooded. So before we talk about architecture and redesigning basements, we ought to do some basic things. We can start by expanding our allowable accessory dwelling units (ADUs) and incentivize homeowners with basements and garages to renovate their properties. California made ADUs legal, and in Los Ange-les ADUs now account for more than 20% of new housing. If California can do it, New York surely can, too.

The last mayor promised to make the construction and preservation of subsidized housing a top priority, and he kept a running tab on the number of apartments that his administration could claim. In doing so, however, he seemed to regard housing as if it were separable from all the things that comprise a neighborhood, which are the things that make a house a home: safe, walkable streets; access to public transit; quality schools and jobs; libraries; healthcare; parks and plazas; food; and culture. We need to think holistically when we talk about housing and rezoning to allow for more subsidized housing. And we need to think in terms of communities, not just units. And we really need to think bigger.

We have a new mayor, and so a chance to reenergize the public conversation. It’s hard not to look back and lament all the ways we got ourselves into this mess—all the bad decisions, the power imbalances, and the subservience to private luxury developers in the pathetic hope of eking some public benefits in the form of affordable units out of them, such as the failure of not wrestling more subsidized apartments out of Hudson Yards, for example. Going further back in time, we can lament the selling-off of much publicly-owned land for a song during the ’80s and ’90s, which we could desperately use now for large-scale affordable housing developments. I would argue we still have some room if we are creative. I’ve done the math, and I believe Manhattan has an average density of 640 residents per acre. There’s a public golf course in the Bronx. It’s 198 acres. You may have heard of it. By my count, 640 x 198 = 126,720 people who could be housed. I’m just saying. And, along the same lines, for reasons that remain mysterious to me, we continue to be cowed by the owner of an aging sports arena that sits atop the Western Hemisphere’s busiest and arguably most miserable and dangerous rail station. The station serves 600,000 working people a day, in a neighborhood that does not need a dozen more humongous office towers that no one will go to, but could sustain an abundance of mixed-income housing in concert with a more robust pedestrian-friendly public realm.

WHOSE CITY IS THIS?

Our COVID streateries aside, I think we have become cautious, defeatist, distracted, divided, sclerotic. NIMBYs often pose as preservationists. A kind of Jane Jacobs-style “People Power,” which arose in response to Robert Moses’s “Powers That Be,” I think too often defaults to a rigid stance of anti-development. A decade has passed since Superstorm Sandy, which devastated low-income housing developments along the East River—and we have just begun the renovation of East River Park, a project that has riven the neighborhood along racial and class lines, and barely begins to deal with the threat of rising seas in Lower Manhattan. Climate change is not going to wait for us to get our act together. Many of you will recall how, a few years ago, activists in Upper Manhattan derailed a 15-story, 355-unit residence on the site of a derelict garage. The project involved a rezoning. The city’s new Mandatory Inclusionary Housing rules required that at least 20% of the units had to be below market rate for a rezoned development. By the way, that number should be much higher than 20% and the affordability requirements much deeper. In any case, the developer was free to put up a 14-story building with no affordable apartments. But in return for the rezoned extra square footage, the developer volunteered to make half of the units—178 of them—rent-subsidized. And opponents still took to the streets, declaring the construction of any new market-rate housing to be “an existential threat to our homes and our community.” The project died.

I understand fears about displacement and losing our neighborhoods. But cities are dynamic and collective organisms. They require sacrifice and involve change. My fear is that we have lost our ability to come together around progress, even to imagine that coming together is possible. We take to the barricades to protest nearly every building proposal. This is not entirely new, of course, but I think the tone has changed. And I think it’s part of a wider pessimism and despair that is a product of the divisions in our country.

Having said that, promising things happen all the time, and I try to make it part of my job to write about them. Housing Preservation & Development (HPD) has been producing affordable housing projects. I wrote about one the other day, a new, deeply subsidized development for seniors in the South Bronx. I also wrote about the renovations at Baychester, a Rental Assistance Demonstration (RAD) project by NYC Housing Authority (NYCHA), again in the Bronx, which turned a decrepit, crime-plagued assortment of leaky, crumbling buildings into a leafy campus of playgrounds and refurbished apartments. Glassed-in entrances replaced old carceral doorways. There are new lobbies, new light fixtures in the hallways, new recycling rooms and compactors, and new bathroom fixtures, windows, and kitchen appliances. It’s mostly cosmetic. It’s not architecture with a capital A. And we’ll have to keep an eye on how the place is managed and maintained. But I gather NYCHA was spending $14,000 a year per unit, pouring cash into deteriorating properties. The new managers are spending $9,000 per apartment. Their costs are lower because the buildings have been upgraded to meet current energy standards and require less maintenance. I’ve talked to a bunch of tenants, and they’re surprised and happy.

They were frightened and skeptical beforehand, and who could blame them? They feared displacement, and who could blame them? The history of NYCHA is a trail of broken promises, false hopes, and abandonment. RAD seemed yet another ruse, which threatened privatization, since NYCHA, by implicitly acknowledging that it was no longer capable of maintaining its properties, was handing over maintenance and renovations to private interests—and on social media and by word of mouth, misinformation about RAD spread like wildfire. And NYCHA, not surprisingly, struggled to counter the narrative.

As I understand it, NYCHA still owns and oversees RAD properties, tenants can’t be displaced unless they fail to pay their rent, private managers can be replaced if they don’t do a good job, and no apartment can be converted to market rate if a tenant moves out. Is RAD ideal? No. Not all developers are good actors. If NYCHA hasn’t been good at overseeing properties, why would it be good at policing private developers and managers? I don’t know. Should the richest nation on Earth build, fund, and run a great public housing system? Yes. And America should also establish a universal right to housing. But in the meantime, hundreds of thousands of NYCHA tenants continue to wait for improvements. Residents at Edenwald, the NYCHA development across the street from Baychester, saw what Baychester got and asked for more of the same. “Seeing is believing,” the president of Edenwald said to me.

That’s the bottom line. We need to get thousands of underserved people affordably, humanely, securely housed. I have been spending time in Houston, the nation’s fourth largest and, it claims, most diverse city, which, a decade ago, had one of the worst homeless problems in the country. I want to end with this anecdote. Since 2012, Houston has cut its homeless count by 63%. A decade ago, a homeless veteran in Houston waited 720 days and had to navigate 76 bureaucratic steps to get from the street into permanent supportive housing. Today, the wait for housing is 32 days. How has Houston accomplished this? And, no—I hasten to say to the crowd here—the lack of zoning is not the answer. It really isn’t. Officials there will tell you, rightly or wrongly, that the lack of zoning, if anything, is a problem, because it doesn’t allow officials to enforce affordability, and meanwhile they’ve got plenty of NIMBYs and covenants and other obstructions.

As best as I can tell, they have done it by coming together. City and county officials, service providers, landlords, downtown business leaders—organizations, politicians, non-profits who ordinarily bicker and compete—have come to the conclusion that they share an interest in fixing the problem, which has trumped their differences. Not everybody is on board, but key players are, including the mayor.

The system is still precarious. Progress is halting and incremental, and Houston is coming up against some of the same affordable housing problems that New York faces. But the city’s success shows us what can happen when businesses, non-profits, and civic and community leaders seek common ground around a problem like housing. I’ll say it again. Surely, New York can do the same—or better.

Oculus thanks Michael Kimmelman for permission to reprint these remarks.

Michael Kimmelman (“Thinking Bigger about Housing”) is the architecture critic for the New York Times, and was previously the Times’s chief art critic. Based in Berlin, Kimmelman created the “Abroad” column, dedicated to cultural and political affairs across Europe and the Middle East. A Pulitzer Prize finalist, he is the founder and editor of the Times’s “Headway” column, focusing on how communities worldwide are addressing their most serious long-term issues.