In no uncertain terms, New York City’s current housing crisis is one of historic magnitude. By some estimates, there is a gap of 600,000 units, which equates to over 1.5 million people, or a population greater than the city of San Antonio, Texas. Worse, current rates of housing production suggest that gap will continue to widen. Much like every housing crisis that our city has endured, this one only became a “crisis” when it began to impact the entire market, not just low-income renters. The warning signs of unaffordability and a lack of accessibility have been present in the affordable housing sector since the last housing crisis over a decade ago, but the severe lack of housing availability is pushing all tiers of the housing market toward a breaking point. This is not simply a supply-side crisis, however, as many have suggested, and we cannot just build our way out of this. While more public dollars for affordable housing and greater housing production in general are critical, we need to resolve a great deal more to prevent the kind of cruel realities that so many New Yorkers now face.

Fifty years ago, in his seminal book Freedom to Build, the urban planner and housing theorist John F. C. Turner included a chapter titled “Housing as a Verb.” In it he explored the semiotic opportunity presented by the word “housing,” which in English can be understood as both a noun and a verb. From this observation, Turner drew the hypothesis that rather than approach housing as a product fueled by industry, we should instead approach the production of housing as a process driven by residents, and that the outcomes of such a shift could be measured by improvements to basic quality-of-life issues, as opposed to a commodity-based set of metrics.

The recent release of “The Housing Blueprint” by the newly elected Adams Administration was met by the expected mix of support and criticism, largely focused on what is seen as a financial commitment that, while unprecedented in size, is still arguably not enough to address the crisis at hand. The blueprint’s clear emphasis on process, residents, and quality-of-life issues, however, runs the risk of getting lost in this discussion. This focus is even more notable as it comes on the heels of a two-term mayoral administration that maintained hypervigilant counts on the number of housing units produced—sometimes at the expense of the same priorities the Adams housing team seeks to elevate.

We should, Turner argues, be “primarily concerned with the impact of housing activity on the lives of the housed, since these issues and problems must be better understood before the wider secondary effects on society can be properly evaluated.” Turner identifies various regulatory and financial barriers to the production of housing that he sees as exclusionary practices. Classist and potentially racist motivations are veiled with claims of minimum standards meant to reinforce what the population in power thinks housing should be or look like. In allowing for more resident agency in decision-making, city government, private developers, and we, as designers, need to prepare for housing, neighborhood planning, and urban design that does not necessarily look the way we think—or thought—it should.

As housers, planners, and designers, we shouldn’t think of this as an either/or equation: top-down versus bottom-up; product-minded versus process-driven. A collaborative process that involves more resident engagement and meaningful community participation in the design process makes for a far better end product. In many ways, most of us who practice in this industry would argue that housing needs to be both a noun and a verb for it to be produced in a way that actually addresses the ever-present need for decent and safe spaces that are affordable, available, and accessible.

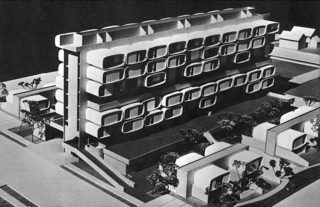

Many of the articles in this issue seek to illustrate just that. “Street Level” features a NYC Housing Authority program rooted in collaboration at all levels, while Dr. Kristin Szylvian’s piece on the U.S Department of Housing and Urban Department’s Operation Breakthrough from the late ’60s demonstrates a federally driven yet locally implemented program that boasted numerous innovations in housing production, which we would do well to reexamine. And Bill Millard’s exploration of what we actually mean when we say “affordable housing” turns our attention to the question of “affordable to whom?”

This is the second year running that the Fall issue of Oculus has focused on the topic of housing and—given the enormity of the current crisis—housing does not appear to be a topic that is going away anytime soon. As co-chair of AIA New York Chapter’s Housing Committee, and on behalf of my fellow co-chair, Peter Bafitis, we are thrilled to have been invited to participate in this issue and hope to make contributions in the years to come. In assembling the pieces presented here, we attempt to explore the process of housing production and conversations around how that process can be improved. In doing so, we endeavor to turn away from our own notions of what housing ought to be or should look like—to reject the notion that housing is a fixed number of units we need to achieve so we can consider the crisis averted, the mission accomplished, the problem solved. Instead, we challenge readers to lean into what housing is: a basic human need, a societal responsibility, a collective action, a verb.

Brian Loughlin, AIA, APA, (“Street Level”) is Director of Planning and Urban Design, Magnusson Architecture and Planning; Co-Chair, AIANY Housing Committee, Division Chair, APA Housing & Community Development; Adjunct Associate Professor of Architecture and Real Estate Development, Columbia GSAPP.