“The point is not just to display beautiful objects,” says Paola Antonelli, the senior curator of architecture and design at The Museum of Modern Art (MoMA). She is describing “Material Ecology,” MoMA’s exhibition on the work of designer Neri Oxman, opening in February 2020. But Antonelli could be describing her entire career, in which she has filled galleries at MoMA and other institutions with striking objects that also illustrate important principles. For more than a decade, Antonelli has been following the work of Oxman, the founder (in 2013) of Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s Mediated Matter Group, which focuses on the relationship between digital and biological fabrication in design and architecture.

Is this a retrospective?

It’s too early for a retrospective! Neri is very young. Shall we call it a mid-career monographic show? Moreover, Curatorial Assistant Anna Burckhardt and I chose pieces that demonstrate new processes and new materials that are projected toward the future, not reflecting on the past.

Some of which might be used by architects?

Absolutely. Neri’s group is working to develop tools that architects and engineers will be able to deploy. Oxman, who originally trained to be a doctor, is known for her close study of natural systems. Back in 2008, when we started showing her work at MoMA, she was trying to understand and mimic nature. She would look at, say, the bark of a tree and try to distill algorithms from its growth patterns and surface behaviors, which she hoped to replicate in, say, building façades. From there her work evolved into harnessing nature directly.

Can you give an example?

Silk Pavilion II, the centerpiece of the upcoming show, is an architectural demo created by silkworms. After study- ing silkworms to understand how they behave in different conditions, Neri and her team created a framework for the silkworms to become the contractors on a building she designed. It’s a very Italian relationship!

How so?

In Italy, it’s considered rude for an architect to draw every last detail; the architect is expected to rely on the crafts- person and their expertise. That’s the relationship Neri has with the silkworms: She’s the architect and they’re the expert contractors.

So there will be silkworms working at MoMA?

There’s a silkworm blight in the United States right now. So the silkworms are working in Italy as we speak, and you’ll see the process recorded on video. The finished pavilion will be at MoMA.

Are there any other living creatures in the show?

Neri is working with bees and ants, but it’s too early for any real demonstrations.

What other processes will the show display?

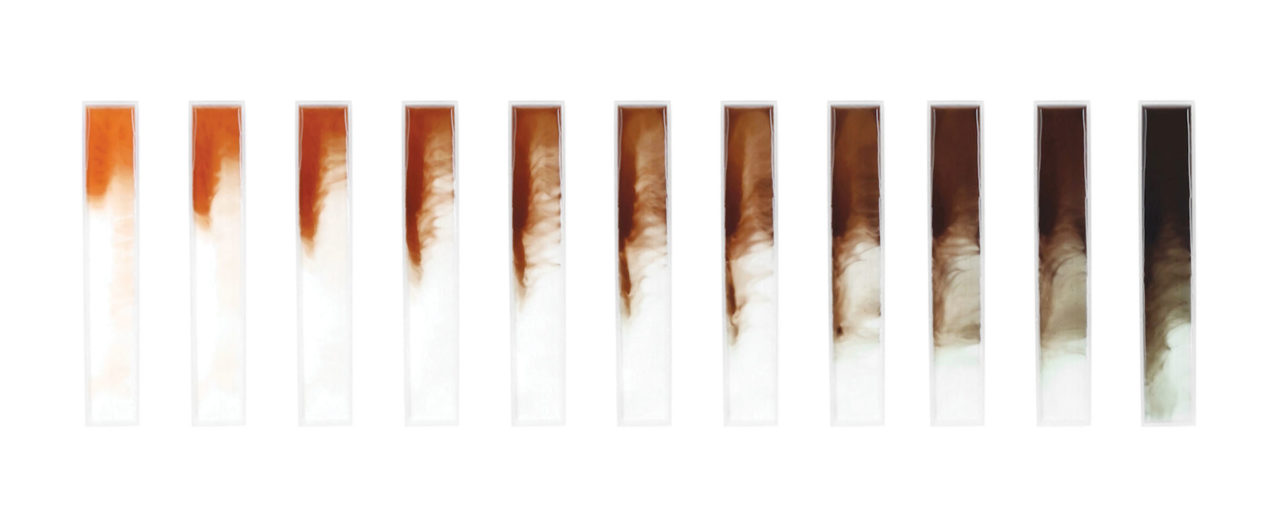

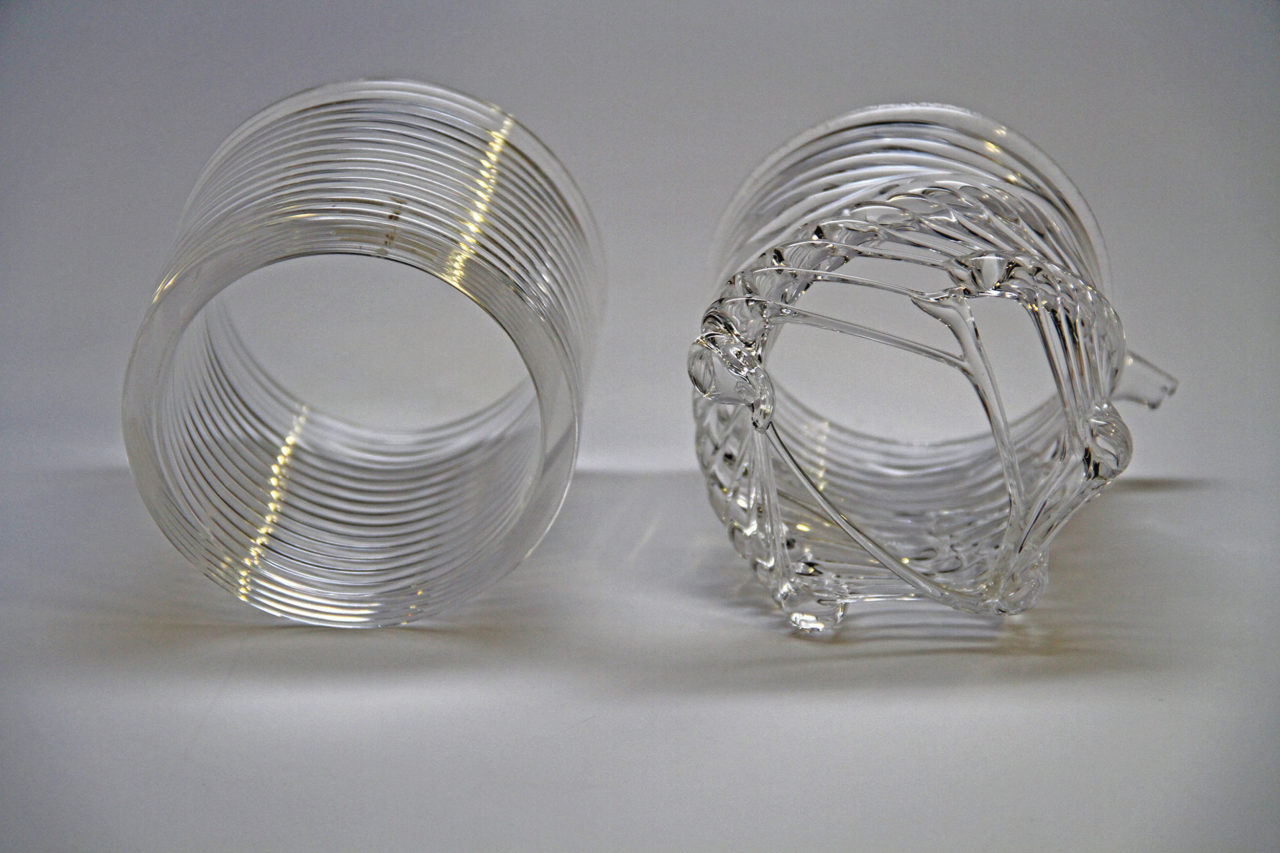

There will be demonstrations of the uses of the pigment melanin at an architectural scale, experiments that could in the future create biologically augmented façades that adjust to the movements and intensity of the sun and other stimuli. And there will be demonstrations of a process for 3D printing glass. We will show about a dozen of her projects, each accompanied by detailed explanations of the process.

Your show “Broken Nature: Design Takes on Human Survival” (which ran at the XXII Triennale di Milano through September) had a startling premise: that the human race may be coming to an end, but we can use design to make the end more palatable, more elegant. Does this show fit that premise?

That is an absolutely accurate description of one of the premises. This show fits the premise because Neri is one of the leaders of the field of restorative design, which is about using design to establish a better relationship with nature.

Will the show address climate change?

In recent years I have been trying to address the climate crisis—which is also a political crisis—in every show I do. In this case, Neri’s approach to the current predicament is to work with nature, learning from natural behaviors and including them in the design and building processes. It’s a step in one of the right directions.

Is Neri doing architecture?

She is, and, as she likes to say, her client is nature. Neri is part of a group of architects and designers, including David Benjamin [whose work at Columbia University and at his firm, The Living, explores architectural applications of biological systems] and Skylar Tibbits [founder of the Self-Assembly Lab at MIT, which focuses on programmable material technologies], who don’t feel the need to define themselves by finished buildings. Rather, they consider it their mission to develop new approaches and put them out into the world. It has happened in the past with people like Bucky Fuller, for instance.

Neri’s work is often very beautiful. Is the urge to make the output look good a distraction from the goal of teaching people about science?

Some scientists are afraid that if their work is too formally elegant, they won’t be taken seriously. That’s always a risk, and Neri is a scientist. But in nature, beauty can be a statement—a way, say, for birds of paradise to attract the attention of potential mates. The beauty of Neri’s work is also a way to attract attention. My job as curator is to take advantage of this attraction to expose the public to the underlying ideas.

What do you hope architects will take away from the show?

I hope architects will appreciate that the new tools are in their arsenal. And I hope they will leave with an enormous amount of inspiration.