Info

Related Links

Topics

-

October 2, 2024

![Image: PLASTARC]() Image: PLASTARC

Image: PLASTARCby Rebecca Lipsitch

In the wake of revelations about hidden labor abuses in certified industries, Melissa Marsh, founder and CEO of PLASTARC, moderated a crucial panel discussion on “Action and Impacts to Advance Equity.” This event marked the final installment of the three-part series “Forced Labor in Supply Chains,” which was inspired by the work of the Design for Freedom movement at Grace Farms aimed at eliminating forced labor in building material supply chains.

The three panelists brought together an assortment of diverse perspectives. Sara Grant an architect, planner, and partner at MBB Architects, is focused on creating equitable, healthy and sustainable environments. Billie Faircloth is the co-founder and research director of the Built Buildings Lab, which highlights the value of existing buildings in the public consciousness, global sustainability practice, and policymaking. Pins Brown is a seasoned expert in business and human rights with 25 years of global experience, focusing on improving working conditions across diverse industries, and is currently a freelance consultant on business and human rights and the Chair of the UK-based Food Network for Ethical Trade.

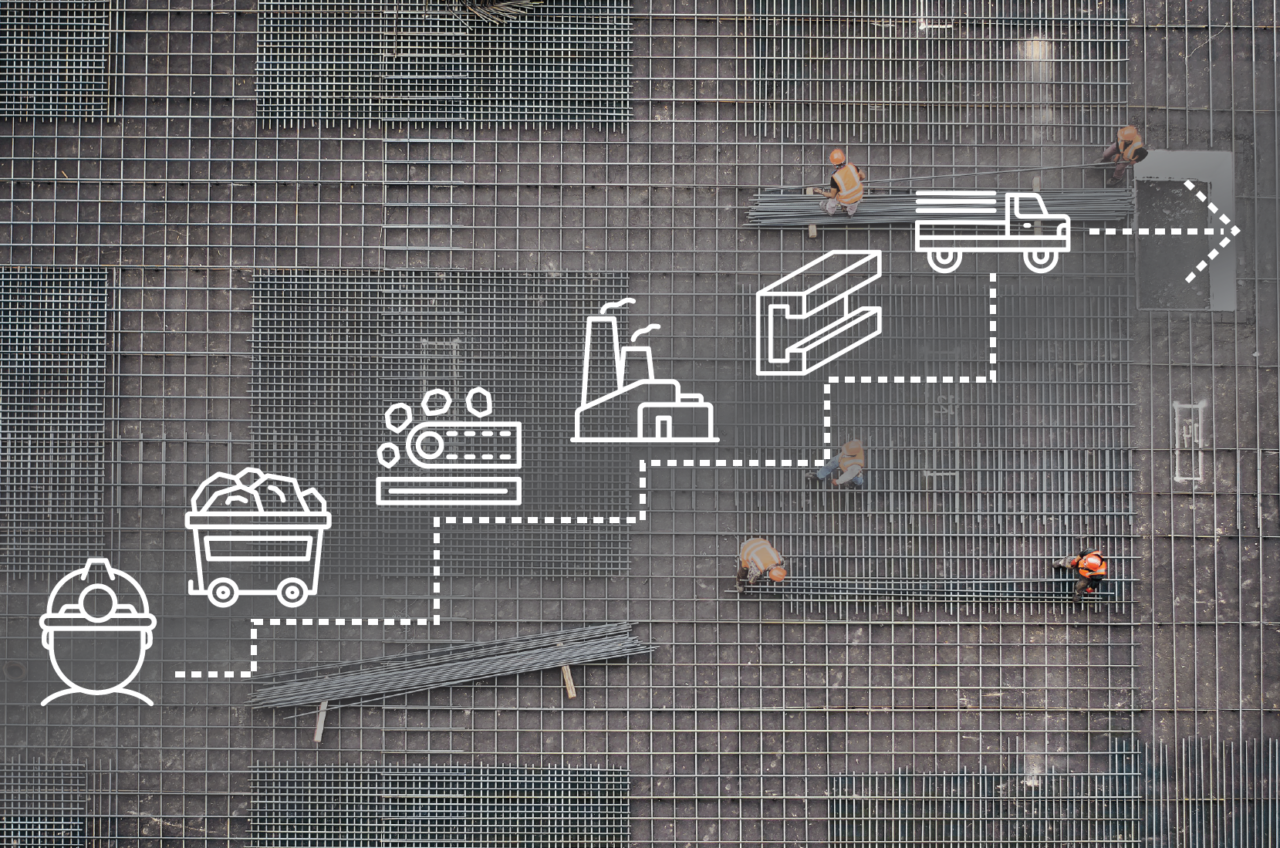

A key takeaway from the panel is the need to address forced labor throughout a building’s entire lifecycle. Just as environmental impact is assessed across the full supply chain, we must examine each stage—from material extraction to construction—to effectively combat forced labor in the building industry. Faircloth spoke about creating methods for designers to assess the risk or likelihood of forced labor in building materials manufacturing, and noted that a consistent challenge has been gaining a comprehensive view of the entire supply chain and creating measurement systems for each stage.

All three panelists emphasized the importance of taking action with available resources, despite complexity and uncertainty. Brown quoted tennis player Arthur Ashe : “Start where you are, use what you have, do what you can,” stressing the need for simplicity to drive action. Grant reinforced this, highlighting architects’ and designers’ ability to make decisions amid complexity and without knowing “everything,” likening it to a good design process. The panelists agreed that to create meaningful, timely change, one must act on current information and make informed estimates, rather than waiting for perfect knowledge. They highlighted the importance of bottom-up approaches.

Grant stressed the need for everyday actions like auditing pay scales, compensating interns, and regularly checking for equity. This ensures organizations address immediate issues, while also tackling larger problems.

Similarly, all panelists, particularly Grant, highlighted the value of building diverse teams that include members from the communities being studied. Brown reinforced this point, explaining that workers often hesitate to answer survey questions, especially when unsure about the questioner’s motives. She noted that outsiders inquiring about worker safety can seem intrusive or even put workers at risk. Therefore, it is critically important to hear directly from impacted communities, despite the challenges in conducting such field research ethically and safely. Including team members who can relate to vulnerable employees is crucial for effective social safeguarding and gathering authentic insights.

During the Q&A portion, an audience member asked about technologies and methods used for gathering sensitive information and community perspectives, without direct interaction. Brown pointed towards the benefits of apps that both train and survey employees at the same time, in order to decrease fear and increase trust early on. Marsh highlighted Sourcemap, a software that does just that, by comprehensive supply-chain mapping, enabling companies to gain visibility and trace and verify their entire supply chain, from raw materials to finished products. Sarah Williams, of MIT’s Civic Data Design Lab, combines her expertise in computation and design to develop communication strategies that expose urban policy issues for wide audiences and promote civic engagement.

The panelists’ acknowledged that this is a complex challenge. Faircloth highlighted the value of being wrong, viewing it as a sign of asking the right questions. Grant invoked the Zen proverb, “Chop wood, carry water,” stressing the importance of daily, consistent effort. This philosophy underscores the need for persistent action, regardless of political shifts.

About the Author:

Rebecca Lipsitch is a socio spatial intern at PLASTARC, entering her senior year of college at NYU Gallatin School of Individualized Study. She appreciates the alignment of qualitative and quantitative research, is fascinated by how human connection is impacted by the spaces we design and create, and hopes to create a more just and ethical society through design. -

September 24, 2024

![Image: PLASTARC]() Image: PLASTARC

Image: PLASTARC![Nina Cooke John | “Shadow of A Face,” Studio Cooke John, 2023 |Photo: Roxane Carré]() Nina Cooke John | “Shadow of A Face,” Studio Cooke John, 2023 | Photo: Roxane Carré

Nina Cooke John | “Shadow of A Face,” Studio Cooke John, 2023 | Photo: Roxane Carré![Diana Kellogg | “The GYAAN Center,” ‘Phase One: The Rajkumari Ratnavati Girls School,’ 2021]() Diana Kellogg | “The GYAAN Center,” ‘Phase One: The Rajkumari Ratnavati Girls School,’ 2021

Diana Kellogg | “The GYAAN Center,” ‘Phase One: The Rajkumari Ratnavati Girls School,’ 2021![Panel discussion: Nadine Berger, Nina Cooke John, Diana Kellogg |Photo: Roxane Carré]() Panel discussion: Nadine Berger, Nina Cooke John, Diana Kellogg | Photo: Roxane Carré

Panel discussion: Nadine Berger, Nina Cooke John, Diana Kellogg | Photo: Roxane Carréby Roxane Carré

Kicked off by Evie Klein, Assoc. AIA,—architect, planner, and environmental psychologist as well as founder of the AIANY Social Science and Architecture Committee—the “Forced Labor in Supply Chains: Examples of a Humanely Built Environment” panel was the second of a three-part series. Led by Sharon Prince, CEO and founder of the Grace Farms Foundation, which intersects nature, arts, justice, community, and faith, the Design for Freedom movement began in 2020: it stands as a “radical paradigm shift to eradicate forced labor in building materials’ supply chain, as demonstrated in its toolkit. Through the kit, architectural studios and firms at any scale can learn more about where their materials come from, who produces them, and how to do away with involuntary work.

This panel spotlighted humanely-built projects by architects Nina Cooke John, AIA, founding principal at Studio Cooke John Architecture and Design, and Diana Kellogg, founding principal at Diana Kellogg Architects. Specifically, it presented concrete ways in which to actualize architects and urban designers’ “moral and ethical responsibility to end forced labor” – per moderator Nadine Berger, architect and sustainability manager at AECOM iLab and SS+A Committee co-chair.

For example, Studio Cooke John’s “Shadow of A Face” (March 2023) in Newark, New Jersey, representing social activist Harriet Tubman, exemplifies humanely-built design. The monument also embodies Studio Cooke John’s mission to transform relationships between people and the built environment, through a multidisciplinary approach and inclusive placemaking. Lastly, the project’s humane construction reflects its role as a physical emblem for Civil Rights and Women’s Rights, characterized by Harriet Tubman—lead social activist in the movements—and replacing a Christopher Columbus statue.

Additionally, Diana Kellogg’s non-profit GYAAN Center in India—a multi-structure campus and women’s community space —represents humanely-built architecture. More than simply using responsibly-sourced materials, the project serves a greater purpose: its first phase, the Rajkumari Ratnavati Girls School (2021) “serves hundreds of local girls below the poverty line in the region” with “tools to further their education and independence.” The project also raises awareness about gender equality in India.

Looking back, Kellogg states that collaborating with Grace Farms and, specifically, with its Design for Freedom toolkit, changed her approach to architectural projects. Indeed, Kellogg now states two non-negotiables in future works: (1) a social giveback and (2) adherence to the Design for Freedom principles.

Echoing Kellogg, Cooke John stressed how important being part of the radical paradigm shift towards humanely-built environments is. In particular, Cooke John pinpointed how conversations with fabricators, instead of just contractors, is crucial for humane building. Personally, Cooke John noted that her (“small”) design firm approached the Design for Freedom principles through a material-tracking spreadsheet. Cooke John explained how working with Grace Farm representatives and with the toolkit had made material tracking more manageable; as a tip to other practitioners, Cooke John mentioned that collaborating with a LEED consultant helps ensure a smooth process. Further, Kellogg advised young architects and current practitioners to start their projects with the Design for Freedom principles, sharing how material selection, or constraints, boosts creativity.

Lastly, to guarantee humane building, both Kellogg and Cooke John reported having been especially mindful of including local culture and residents throughout the design process. Indeed, Studio Cooke John’s “Shadow of A Face” (2023) is part of a larger initiative to include communities in urban design processes and in a city’s socio-cultural fabric; Cooke John spotlighted the initiative, “Will You Be My Monument” which intends to “celebrate Black girls” and ask “What stories should be told in public spaces?” To this end, Cooke John shared how Newark residents had been invited to inscribe their own stories onto the Harriet Tubman monument for representation and collective memory.

Moreover, according to Cooke John, the Harriet Tubman monument has become more than architecture: in enabling local residents to “recognize[] their own stories in front of Harriet Tubman’s historical legacy,” the structure transformed into “a place of collective memory across space and time.” Adding to the monument’s significance in the public realm, Cooke John shared how “Shadow of A Face” (2023) has become “a place for community, performance, and occasional protest” instead of being just a park in which people walked through. Cooke John ended by underlining the importance of community engagement inside architectural and planning processes within urban areas to enable “feelings of ownership” from communities and residents. On this, Cooke John stated that “the city landscape… becomes activated only once the community activates it.”

As another perspective on humanely-built architecture, Kellogg shared wanting the GYAAN Center to be a home for young Indian girls living under the poverty line to pursue their education and independence. Precisely, the Center was to be a refuge where the girls could feel “safe, comfortable, nurtured, and free” (Kellogg, 2024). To ensure the project respected cultural norms and values, or pushed against them to support the DforF movement as well as benefit the girls (i.e. eradicating forced labor, including youth work), Kellogg’s team included local Indian women. Notably, Kellogg shared that during interviews the girls attending the Rajkumari Ratnavati Girls School reported “(…) f[eeling] safe there.” Since then, attendance has broken records for local schooling: a testament to the school’s purpose, need, and success as a learning haven.

To continue moving toward sustainable practice and social equity, organizations and practitioners in architecture need to examine their supply chain, reflect on material sourcing, and adhere to humane design principles all-around—Grace Farms’ Design for Freedom toolkit, easily accessible for download at the link, is a great place to start.

If you are interested in continuing or joining the conversation, please see below for the other events in the three-part series and information on joining the SS+A committee:

- Forced Labor in Supply Chains: Taking Action (the 3rd event of the series) [July 8th, 2024]

- Join the monthly Design for Freedom Office Hours. These calls are open to the public and happen on the first Thursday of each month at 12:00pm ET.

- Join the monthly AIANY Social Science + Architecture Committee committee meetings. They are open to the public and typically take place from 8:30 am–10:00 am ET on the fourth Friday of each month.

About the Author:

Roxane Carré is an independent researcher, freelance creative, and interdisciplinary strategist. Roxane is a recent graduate in sociology, economics, and psychology from Barnard College of Columbia University and holds certifications in urban planning & design from the Harvard Graduate School of Design and sustainable & strategic design from IE University, Madrid, Spain. At AIANY | Center for Architecture, Roxane is a member of the Social Science and Architecture Committee and acts as a liaison between the Interiors, Committee on the Environment (COTE), and Future of Practice committees, easing communications and event planning. Next, Roxane will be pursuing graduate studies in urban design, overseas. -

April 5, 2024

Please join us for the AIANY Social Science and Architecture Committee’s Spring Happy Hour, to be hosted at Savant’s beautiful experience center in SoHo!

Whether you’re a member, a friend, or just curious about what we do, we’d love to see you there.

Please RSVP by April 9 if you think you’ll be able to attend (not required, just to give us an idea about numbers!), and feel free to forward this message or bring along friends who might be interested too! The more, the merrier.We look forward to seeing you there!

Cheers,AIANY SS+A -

February 12, 2024

![Confronting Modern Slavery in Construction Supply Chains Image 01]()

![Confronting Modern Slavery in Construction Supply Chains Image 02]()

By Ian Wach

How is modern slavery embedded in the built environment? More than 12 common building materials—including timber, copper, silicone, and PVC—are at risk for forced labor in their supply chains.

Bringing awareness to this issue and highlighting potential solutions was the purpose of the Social Science and Architecture Committee’s event Forced Labor and Supply Chains: Its Prevalence and the Design for Freedom Movement, which took place at the Center for Architecture on December 12, 2023. This was the first event in a series of panels and workshops designed to invite stakeholders in the building industry to think about ways to reduce the ethical footprint of our buildings by working to eliminate forced labor.

This series kicked off showcasing the work of Design for Freedom, a movement to create a radical paradigm shift and remove forced labor from the built environment. Design for Freedom emerged from the Grace Farms Foundation, whose mission is to end modern slavery and foster more grace and peace in our local and global community. Sharon Prince, CEO and Founder of the Grace Farms Foundation, initiated Design for Freedom following a series of conversations around ethical sourcing, after realizing that designers often do not know where the materials used to construct their designs come from and under what conditions workers produced them.

Today, Design for Freedom engages with a broad spectrum of professionals and students to address the problem of modern slavery in the built environment. This entails architects, engineers, owners, construction teams, suppliers, and academics in order to extend the conversation to the entire building ecosystem.

In light of these roots and to kick off this series, Social Science and Architecture Committee member Nadine Berger (Sustainability Senior Manager at AECOM) introduced the speaker, Brigid Abraham (Design for Freedom Project Manager at Grace Farms). Abraham brings experience in architecture and information science, as well as a passion for architectural research, to furthering the goal of Design for Freedom.

Abraham discussed that modern slavery is defined as situations of exploitation that persons cannot refuse or leave because of threats of violence, coercion, deception, or abuse. According to the 2023 Global Slavery Index by Walk Free, an international human rights group working to end slavery, there are 50 million people living in modern slavery. Forced labor, which Abraham described as a subset of modern slavery, can be identified by factors including “restrictions on workers’ freedom of movement, withholding of wages or identity documents, physical or sexual violence, threats and intimidation or fraudulent debt from which workers cannot escape,” according to the International Labor Organization. There are an estimated 28 million people living in forced labor.

Abraham continued by stating that construction is the second most at-risk sector for forced labor, following manufacturing. This includes site work, as well as the procurement of the various raw and composite materials used in construction. Material procurement, which accounts for about 45% of construction expenditures, is obfuscated through a complex network of subcontractors, manufacturers, and raw materials producers. Construction lags behind other sectors, such as agriculture and clothing manufacturing, in terms of awareness of issues of forced labor and working conditions in the supply chain.

Moreover, Abraham posited that forced labor in construction also intersects with the decarbonization movement. For example, the Global Slavery Index identified solar panels as one of the five most valuable high-risk products for forced labor. To ensure we are on a path towards ethical decarbonization, the Design for Freedom lens asks us to identify and eliminate exploitative labor practices, as well as ecologically harmful processes, in raw material extraction, manufacturing, and construction.

Given the complexity and scale of the issue, Abraham listed a series of avenues being pursued by Design for Freedom and others, including:

- Embedding standards in existing codes of conduct and industry certifications: Design for Freedom worked with the AIA on the Social Health and Equity section of the AIA Materials Pledge. Design for Freedom is also in conversations with the U.S. Green Building Council, Health Product Declaration Collaborative, and WELL.

- Technology for Supply Chain Mapping: Companies are providing novel approaches to understanding and identifying potential issues in the supply chain. Altana AI is developing tools for companies and customers to understand their supply chains. Fair Supply provides ESG compliance assessment tools that help identify supply chain risks for forced labor.

- Laws and Regulations: The German Supply Chain Act in 2023 suggests the potential for additional regulation in the EU. In the U.S., the Uyghur Forced Labor Prevention Act created a framework for the Customs and Border Protection to impound and reject products and materials made with forced labor originating from the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region.

- Dialog with Manufacturers: In November 2023, Design for Freedom held an Ethical Supply Chain Forum to bring the manufacturing community into the conversation. Manufacturers can be hesitant to pull out of certain regions and economies. It is important to note that this is not the intent of Design for Freedom. An ideal next step for manufacturers is to seek remediation in their supply chains by ensuring freedom of movement and adjusted living wages.

- Pilot Projects: Design for Freedom’s pilot program currently includes 8 projects located in the U.S., the UK, and India. For each pilot, Design for Freedom acted as a collaborator advising on ethical and transparent materials procurement. The new round of pilots for 2024 will be announced at the 3rd Annual Design for Freedom Summit.

Additionally, Design for Freedom has created a series of resources to help spread awareness of the issue of modern slavery in the built environment. Their resources page contains a list of reports and statistics. Furthermore, the Design for Freedom Toolkit provides a deep dive on the 12 at-risk building materials and points to strategies for design and construction professionals to mitigate their use of materials created with forced labor.

If you are interested in continuing or joining the conversation, please see below for a list of upcoming events:

- March 11, 2024 – Forced Labor in Supply Chains: Examples of a Humanely Built Environment (the second event of this series)

- March 26, 2024 – 3rd Annual Design for Freedom Summit

- Join the monthly Design for Freedom Office Hours. These calls are open to the public and happen on the first Thursday of each month at 12:00pm ET.

- Join the monthly AIANY Social Science + Architecture Committee committee meetings. They are open to the public and typically take place from 8:30 am–10:00 am ET on the fourth Friday of each month.

About the Author:

Ian Wach is a researcher and strategist with a background in real estate and architecture. He is a member of the Social Science and Architecture Committee and works as a Senior Consultant at Buro Happold.

-

October 16, 2023

![Toward an Architectural Education with an Awareness of Advocacy Event Photo 02]()

![Photo: Kuan-Ju Chen]() Photo: Kuan-Ju Chen

Photo: Kuan-Ju ChenArchitecture is a potent instrument for addressing societal, cultural, and environmental challenges. As practitioners, we can leverage design to tackle issues like climate change, inequality, and urbanization, crafting solutions that empower and uplift – and architects will need to do even more of this in the future.

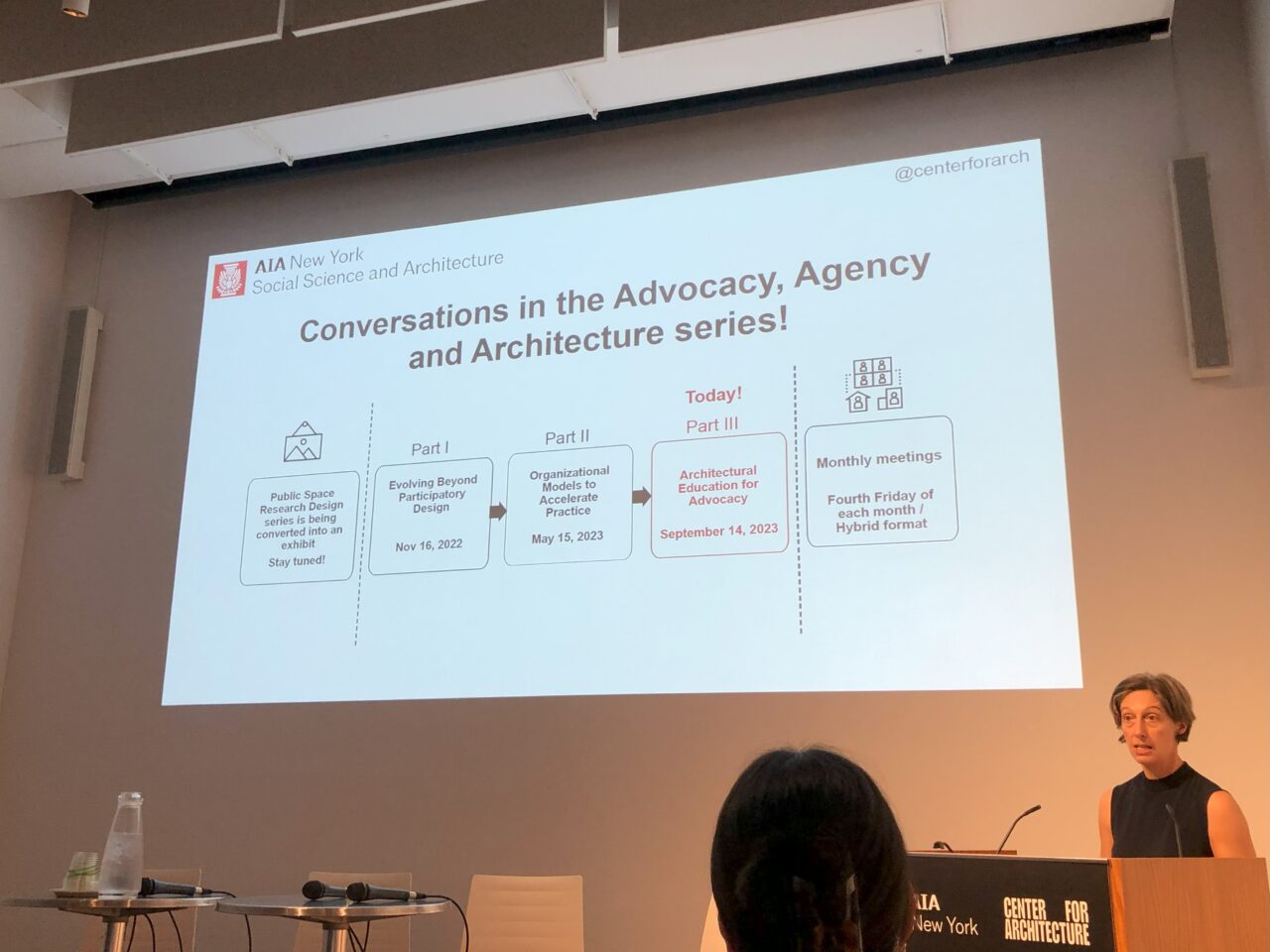

On September 15, 2023, the Social Science and Architecture Committee hosted a panel titled Toward an Architectural Education with an Awareness of Advocacy. This gathering brought together architects, educators, and students to explore the pivotal role of advocacy in architectural education. Their insights shed light on the challenges faced by architectural education and the innovative approaches required to address them.

Committee member Sara Grant (Partner, MBB Architects) moderated, and our panelists were:

- Kelsey Jackson, M. Arch Candidate at Columbia GSAPP; Junior Designer, FXCollaborative

- Jieun Yang, Founding Principal, Habitat Workshop; Assistant Professor, CUNY New York City College of Technology; Leadership Group, Design Advocates

- Sanjive Vaidya, Chair of the Department of Architectural Technology, CUNY New York City College of Technology; Board of Directors, The Architectural League of New York

- Kristen Chin, Director of Community and Economic Development, Hester Street

This panel was the third and final event of the Advocacy and Agency in Architecture series, the first two events of which looked at architects’ advocacy in their work impacting communities (“Evolving Beyond Participatory Design”), and architects advocating for themselves through non-traditional organizational models (“Organizational models – Acceleration in Practice”).

Architectural education has traditionally focused on technical skills and design principles, with the demands of accreditation failing to leave room for much else. However, the profession needs to adapt so that it – and its newest generation – are equipped to address the myriad of global climate and social crises that continue to emerge, impacting the built environment.

Kelsey, who is taking a year off from her architectural master’s program, had felt that her architectural studies were disconnected from both her individual interests as well as what was happening in the world. This was in stark contrast to the progressive primary school in Spain where she had worked, where students were encouraged to take control of their own learning. The focus was on nurturing agency and self-confidence, allowing students to set the agenda and teach classes, emphasizing the value of collective capacity.

The lessons learned from this pedagogy serve as a foundation for reimagining architectural education: encouraging students to learn through exploration and self-discovery, and ultimately preparing them for the dynamic and evolving field of architecture.

Jieun’s experience with Habitat Workshop and CUNY highlighted the importance of engaging students early in their architectural education. She discussed her pre-college program that introduces students to architecture through the use of simple prototyping materials and practical experiences such as taking time to understand and document their neighborhoods and working with local community organizations, using the city as a laboratory. For many students who believe “there’s nothing” in their neighborhoods, Jieun pushes them to look again: “There’s got to be something.”

In her eyes, architecture is a form of inviting relationships. Her approach not only provides a solid foundation for future architectural studies but also demonstrates to students a new way of seeing and thinking about the world around them and how they can have a tangible impact.

Sanjive, the architectural department chair at City Tech, highlighted the unique opportunity and responsibility of his program, given the extreme diversity of his students. The discussion raised questions about how to reframe architectural education, shifting from a focus on final products to celebrating the process, and how to make space amidst stringent accreditation requirements for needed changes – such as developing skills for critical inquiry, or ensuring the diversity of the student body is represented in the available coursework.

Recognizing that anyone coming into architecture has optimism and hope, Sanjive sees it as the responsibility of architectural programs to steward and cultivate that hope. Equipping students with the ability to ask meaningful questions and seek answers is an essential skill for tomorrow’s architects, as they are increasingly expected to be problem solvers who must help our society adapt to a changing world.

Kristen, representing Hester Street, highlighted the significance of community-centered design and exposing architecture students to this process, with the goal of architects being more aware of the communities they serve, particularly in underrepresented areas. Hester Street is engaging students in this practice through a new paid fellowship program called the Jim Diego Fellowship. She noted that there is a lack of design firms that truly represent the communities they work with.

Architects need to understand that their role goes beyond creating structures; they are catalysts for change and transformation. Inclusivity is key, ensuring that materials for engagement are understandable, accessible, and applicable to the communities they serve. Building relationships with community members is paramount to effective and ethical architectural practice.

As the architecture profession evolves, so too must architectural education. There is a need to teach students alternate modes of practice, focusing on programmatic longevity and adaptable design thinking, if architecture is to stay relevant in the future.

Architects must be prepared to engage with community members and empower them to have agency over their built environment – and that must start in students’ formal architectural education. Architecture is no longer just about designing beautiful structures; it is about empowering architects to shape a better world. We must cultivate the next generation of architects who can ask meaningful questions, build relationships with communities, and embrace an ever-changing landscape. It’s about training architects to understand the value of vulnerability, and recognize that building relationships is as important as constructing buildings.

In this vision of the future, architects lean into their role not just as designers but also as changemakers. It’s a future where architectural education is not limited by tradition and stifled by standards but is dynamic, inclusive, and responsive to the changes our society needs from architects. In this future, architects are better equipped to create a built environment that truly protects and serves the needs of all, and provides a place for all to thrive.

For those interested, please consider joining the conversation by:

- Attending our upcoming public events. Our next event series kicking off on November 2nd, will focus on the prevalence of forced labor in building materials – and what you can do about it. Details will be posted to AIANY’s Calendar prior to each event.

- Joining the AIANY Social Science and Architecture Committee Monthly committee meetings. They are open to the public and typically take place from 8:30am-10am on the fourth Friday of each month.

About the Author

Kate Ganim is a designer and strategist with a background in architecture. She is currently a co-chair for the AIANY Social Science + Architecture Committee and a Strategy Director at Artefact.

Committee Meetings

-

Fri, 11/22, 2024, 8:30am

-

Fri, 12/13, 2024, 8:30am

Past Events

-

Mon, 7/8/24, 6:00pm

-

Mon, 3/11/24, 6:00pm

-

Tue, 12/12/23, 6:00pm

-

Thu, 9/14/23, 6:00pm

-

Wed, 7/26/23, 6:00pm