Urban ecology is, as of late, no longer a contradiction in terms. If ecology elsewhere is something that just happens, in cities it requires more effort to preserve and promote. A number of practices spanning architecture, landscape architecture, and adjacent design fields have honed their craft in increasingly innovative ways in recent years in pursuit of climatic mitigation, habitats for wildlife, and thriving green space for humans. Here we share a variety of approaches that firms have been taking to confront a linked and overlapping range of ecological, social, and civic challenges.

Chris Reed

Founder and Design Director, Stoss Landscape Urbanism

Boston, MA

What is or was your defining project of the last year?

Triangle Park, Cambridge, MA

Triangle Park is the city’s first demonstration and iteration of its urban forestry plan. It stems in part from many years, or decades, of cities working from a small, select list of trees they thought were best for urban streets. Here, the city asked, “Why can’t we do more in terms of biodiversity, and in terms of planting and maintenance practices that might ensure better outcomes?” Historically, if a street tree dies out suddenly, it’s like somebody lost a tooth. At Triangle Park, we used almost 24 new species instead of six. This allows for natural competition among individual trees and species. If you have a biodiverse group of trees and some die off , it isn’t a crisis because it just leaves room for the species that are thriving.

There are other recent biodiverse micro forests, but they’re not always designed as real social spaces. We wanted to say there’s room for people in this mix. We thought it was important to design it as a social space, but as one that still had all these trees.

What is your biggest challenge?

It’s obviously climate change—and especially how we deal with that from a governance and jurisdictional point of view. We all know what the scientific challenges are, and how design can help us adapt, but climate change raises issues that are cross-jurisdictional. The solution doesn’t end at your property line. If the person next to you isn’t in sync with what you’re doing on flood control, water is going to get into your property (and theirs). This applies to both private and public property. Consequently, we need to set up commissions that cut across traditional lines of governance, that can work in a cross-disciplinary and cross-jurisdictional way. Whether it’s a small-scale or a large-scale site, we inevitably need to have these conversations where broader systems and solutions are coordinated.

What’s a rule you like to break?

The one I would suggest breaking is the adage “stay in your own lane.” For us as designers, it has always meant thinking far beyond the extent of the site we’re dealing with: What are the bigger social, cultural, and economic forces at play, and how can we work with larger-scale systems, even at a local level? With the climate crisis and ongoing social/racial/ethical reckoning, we need to have different kinds of broad conversations. We’re not ecologists, but we need to know ecology; we’re not engineers, but we need to know engineering; we’re not sociologists, but we need to be very deeply involved in community conversations. Start deep within your own disciplinary training, for sure, but look far beyond the edges to address the complex problems we face.

Terrain-NYC

New York, NY

What is or was your defining project of the last year?

Morningside Gardens Renovation New York City, NY

A defining series of projects in 2023 was our ongoing work, rehabilitating and reimagining modernist-era housing throughout Upper Manhattan and the Bronx. Th is includes the completion of our Morningside Gardens landscape renovation, just north of Columbia University. The cooperative apartment campus was in serious need of renovations when we were hired in 2017. It became a case study in preservation, community engagement, building on the legacy of modernist landscape architects, and addressing contemporary problems, such as accessibility and decentralized stormwater management.

We were also busy designing at eight New York City Housing Authority (NYCHA) sites from the same era. It is immensely powerful and gratifying to be devoting our office’s resources to the reimagining of these sites with the residents who call them home. Our work often extends beyond landscape architecture and touches on aspects of social and environmental justice as we work with the Tenant’s Associations and private developers through NYCHA’s PACT program.

What is your biggest challenge?

As landscape architects, we see the impacts of climate change firsthand; sites are flooding that never flooded before, and new plant species are thriving. The NYC Department of Environmental Protection’s revised Stormwater Manual and Stormwater Pollution Prevention Plan requirements—meant to address the results of climate change—are impacting nearly every project in our office. These regulations provide agency to land-scape architects to play a bigger role in designing stormwater infrastructure and, because such interventions are required by code, we see real opportunity for additional quality public space as a result.

What’s a rule you like to break?

It’s not breaking a rule per se, but our office gathers every other week for an in-person design workshop where we draw together. That time spent drawing is incredibly productive. We may have eight or 10 designers quickly developing ideas. We believe that working this way helps us get to the heart of the design issue quickly and identify areas outside the original brief that are worthy of exploration, which can add value to our projects. It also creates consistent design opportunities for our staff and, we think, keeps our design ideas fresh.

Rachely Rotem and Phu Hoang

Founding Directors, Modu Architecture

Brooklyn, NY

What is or was your defining project of the last year?

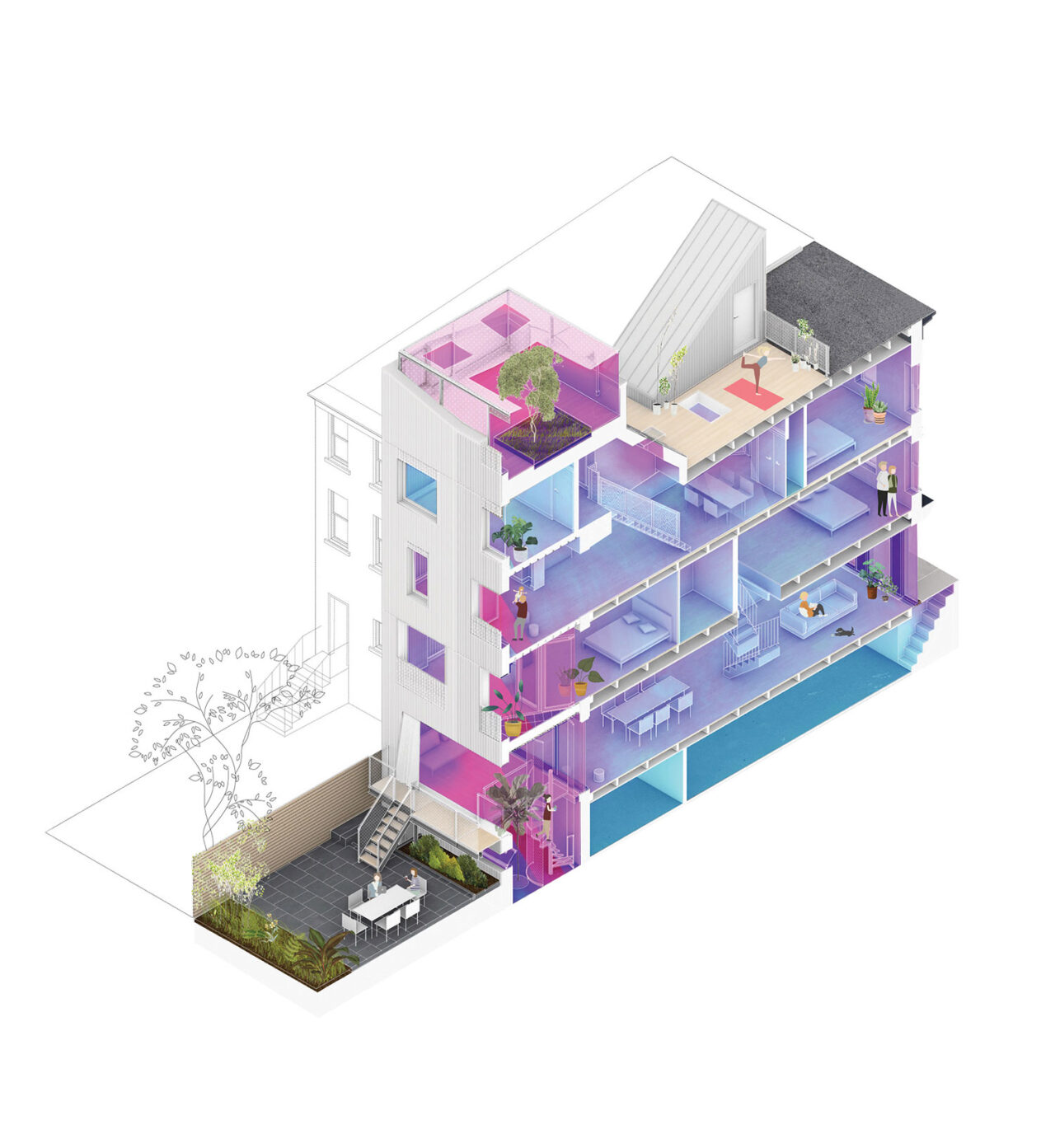

Mini Tower One, Brooklyn, NY

Mini Tower One is an extension to a multifamily residential building in Brooklyn. This extension, adhering to passive house principles, reduces energy consumption during extreme weather seasons and features multiple indoor-outdoor living spaces, fostering connections with the outdoors during milder seasons. The addition serves a dual purpose: it acts as a precooling buffer for incoming air, and it provides residents with a panoramic view of the changing seasons.

The project initiated our Mini Towers research—it serves as a prototype for urban development, mapping potential city sites for similar constructions. Each lot is characterized by small footprints that offer vertical expansion possibilities. This strategy introduces diverse microclimates into New York’s housing stock and offers versatile floor plans, ensuring adaptability and growth over time. It’s a blueprint to address New York’s housing shortage while offering varied experiences with urban natures.

What is your biggest challenge?

Our challenge lies in reimagining architecture not as isolated structures, but as components of a broader environmental system, encompassing ecological, climatic, and sociocultural aspects. Instead of confining design within traditional inward-oriented exterior walls, architecture can extend outward, integrating and interacting with its surrounding environment. This approach involves designing for varied microclimates that cool air before it reaches exterior walls, thus reducing energy usage and enhancing residents’ well-being. Features like public shade areas and enhanced biodiversity can benefit a local community, contributing to the creation of a more inclusive city.

What’s a rule you like to break?

Every rule can be broken, but the key lies in identifying which rule to break based on the opportunities it presents. We believe that constraints are powerful catalysts for design innovation. Clear programmatic, climatic, financial, and functional constraints are the foundation of a creative design process. Within these boundaries, open-ended design processes can uncover a rule that can be broken, leading to architectural innovations and the potential for living better. This understanding guides when and why a rule can be broken.

Dirt Works

New York, NY

What is or was your defining project of the last year?

West Pond Living Shoreline Jamaica Bay Wildlife Refuge, Gateway National Park, Queens and Brooklyn, New York

For the West Pond Living Shoreline project, we considered the complex interplay of a shifting estuarine ecosystem and the National Park Service’s programmatic and accessibility goals to reestablish, protect, and sustain its critical marsh habitat. Breakwater structures, additional sediment, marsh plantings, and erosion control coalesce to attenuate wave action, improve water quality, and support the reemergence of mudflats and salt marsh. This living framework supports pond edge restoration while adapting this vulnerable ecosystem to the challenges of climate change. A “breakwater burrito” was created by packing recycled oyster shells from local restaurants in burlap, stacking these in a pyramidal structure, and wrapping the entire 12-foot-long structure with coir fabric. These breakwater structures together with recycled Christmas tree fascines attenuate wave action, accrete sediment, and protect the newly constructed shoreline.

We repurposed 70,000 cubic yards of fill from construction at JFK Airport to establish nine acres of new habitat and 2,400 linear feet of shoreline. Silt sock barriers, which allow water to flow through at a controlled rate while trapping sediment, were installed for 680 breeding terrapin females. In addition, we placed 240,000 native plantings in salt marsh and intertidal zones, creating a resilient ecotone between the high marsh and the freshwater pond. Ongoing monitoring and data-driven research will sustain and inform this living shoreline design.

Protecting and sustaining West Pond is critical to the resiliency of the larger Gateway National Park ecosystem. Equally critical is protecting and sustain-ing the idea of community stewardship. This multidiscipline, community-based initiative establishes an effective and vital response to our changing climate.

What is your biggest challenge?

Our biggest challenge is navigating the permitting process. We often want to try more groundbreaking techniques for pilot projects, and have to balance this approach with regulatory reviews. We are particularly interested in oyster reefs as breakwater structures, but have found them challenging to use because many clients and agencies see these as an at-tractive nuisance.

What’s a rule you like to break?

As landscape architects, we like to follow rules while taking design risks. Our design risks include incorporating elements that add a layer of thought and research to projects. This could be a braille rail with poems for visually impaired users, deck board patterns that mimic the sonogram of native bird songs, or plantings that encourage a sensory experience.

Barbara Wilks

Founding Principal, W Architecture and Landscape Architecture

Brooklyn, NY

What is or was your defining project of the last year?

Shoreline projects, Brooklyn and Queens

Many of our urban projects involve reimagining and making public formerly disturbed and isolated private areas. This past year, our projects at Bush Terminal and the West Wharf, in Brooklyn, and Downtown Far Rockaway Streetscapes and Plazas, in Queens, are good examples of reintegrating such places back into the community, while also making them more inviting to other species. Bush Terminal was carefully designed to reinterpret the unique historical aspects of this former bustling transfer hub by opening the waterfront to the public, with multiple spaces for gathering for the rechristened Made in New York campus. West Wharf opens Greenpoint to the East River, providing a variety of pedestrian environments, including woodlands and beaches. A diversity of seating types and areas invite gathering and strolling. Far Rockaway provides greater pedestrian amenity and safety, rebalancing vehicular, pedestrian, bike, and bus networks to extend public space throughout downtown, and connecting the A train terminal to the Long Island Railroad.

What is your biggest challenge?

It’s always a challenge to make unique places that derive from the geography of the area and the people involved. We like to make places that feel welcoming and of the place, not alien. On many occasions, traces of former inhabitation have been erased, and many types of research are required to reestablish identity. We look to leave a place more diverse and healthier than we found it.

What’s a rule you like to break?

Why do streets look similar, no matter where we are in the city? If we could walk through the city as it was in the 1600s, there would be great diversity in the environment. Could streets tell us more about where we live? For instance, if we live in a low-lying area, could the streetscape reflect a wetland environment, helping to control flooding as well as providing identity? Are there areas that could be considered for future forests? Could parking spaces, for instance, become linear forests? We’d like to see more innovation in rebalancing public space for people and for greater health. This would include more space for a diverse nature.

Future Green

Brooklyn, NY

What is or was your defining project of the last year?

New Jersey Performing Arts Plaza, Newark, New Jersey

One of our defining projects of the last year is the New Jersey Performing Arts Plaza (NJPAC) in Newark, New Jersey. NJPAC is the heart of an emerging arts district that includes a series of mixed-use buildings, low-rise residences, and a new community arts center situated within a pedestrian-friendly streetscape of connected green spaces. Designed as Newark’s outdoor living room, the performance plaza provides an inclusive and flexible framework that, day-to-day, provides the local community with a much-needed vibrant, open-space to enjoy. The plaza transforms in the evenings and seasonally to accommodate a wide array of events and programming. This inclusive approach to a civic plaza attempts to break down the traditional hierarchies associated with cultural institutions. Rather than serving to place the institution on a pedestal, NJPAC’s leadership encouraged a reworking of the typical narrative, allowing community input to drive the plaza’s design intention.

A connective stone carpet unites the district with a series of programmatic interventions, such as a large flexible lawn, multi-directional stacked seating, a social circular bench, and oversized movable lounge chairs. A series of truss-like vine columns anchor the central stage, providing support for temporary tent structures and theatrical lighting. The planting scheme is designed with the ecological, poetic, and seasonal performance of the plants in mind. This ecological framework serves the local flora and fauna and helps mitigate pressure on the adjacent Passaic River.

What is your biggest challenge?

An ongoing challenge in our work is advocating for a commitment to environmental responsibility when those principles don’t always align with the bottom line or client comfort. This can affect material choices, plant selections, and even the sourcing of high-quality soils. With wood, for example, we typically specify reclaimed products and native hardwoods such as black locust as alternates to tropical hardwoods, but clients will often want to use materials that they know or that fit their budgets. We have had the most success in convincing our collaborators of the value and durability of less well-known, but more sustainable materials when our arguments are grounded in research and experience.

What’s a rule you like to break?

Our practice deviates from the standard model of a landscape design office. We work out of two locations: We have a design office and fully equipped woodshop in Red Hook, Brooklyn, and a farm, metal shop, and satellite office in Chester, New York. We are a collective of designers and makers and our work creates an invaluable feedback loop that increases institutional knowledge, capacity, efficiency, and the ability to come up with elegant solutions.

ANTHONY PALETTA (“The Pathfinders”) is a contributor to The Wall Street Journal, Metropolis, The Architect’s Newspaper, Architectural Record, Financial Times, and other publications. He lives in Brooklyn.