- Introduction

- +Essays

- Editor's Note

- Zoning as Design

- Towards A City of Cities

- The Future of the Zoning Resolution

- Zoning and Design Visualization

- Working with the City

- A Revolutionary Approach to Zoning

- Zoning the Next 100 Years… Or At Least 50

- Vision and Legitimacy: The Planning Basis of Zoning

- Happy 100th Birthday, NYC Zoning Resolution!

- Reflections on the 100th Anniversary of the NYC Zoning Resolution

- Regulating the Good You Can't Think Of

- Zoning for the 21st Century Metropolis

- The Zoning Resolution: A Work in Progress

- Zoning for Tomorrow

- Zoning and Design: It’s Complicated

- What’s Old Is New

- Zoning – The First 100 Years

- One Hundred Years of Zoning

- 100 Years of Zoning

- Authors

- Related Links

- Events

Working with architects and developers for the past nine years as the Deputy and now Chief Urban Designer of New York City’s Department of City Planning, one thing became very clear: some of our zoning rules were getting in the way of good design. This is a functional problem as much as an aesthetic one—because good urban design marries the best of both. Like any long-term relationship—and zoning is nothing if not long-term —it’s complicated.

But in all things urban, hope springs eternal: In March, NYC passed legislation that revamps the city’s zoning codes. Called Zoning for Quality and Affordability, ZQA, was the first major re-write of zoning in over fifty years and will shape the city for decades to come. From micro-units to ground-floor retail in affordable housing to parking and neighborhood character, the city has tackled small, medium and large urban design challenges in the most ambitious set of zoning code changes since 1961.

There will be many debates about the finer points of ZQA’s impact. But one thing I know for sure: the new codes respond to the challenges of dense urbanization in the 21st Century—both functionally and aesthetically—by increasing flexibility, emphasizing the pedestrian experience, and embracing the way people are already reshaping the way we live in the city today.

ZQA: S,M,L

Small: Micro-units. Increasing Housing Options for the 21st Century

How we define private and public space has changed radically over time. As Richard Sennett explored in his seminal book: The Conscience of the Eye: The Design and Social Life of Cities, in the industrial era, “The public world of the street was harsh, crime ridden, cold, and above all, confused in its very complexity. The private realm sought order and clarity through applying the division of labor to … the family, partitioning its experience into rooms.”

While there was little separation of function in the medieval house, by the middle of the 19th century, as industrialization was well underway, public and private areas of the house were delineated. In New York, this division of public and private space is what led to the railroad apartment, with more public rooms segueing into the most private.

“In retrospect,” Sennett continues, “we see the tenement as the devil’s construction. As these apartments were abandoned to the poor, each railroad flat became like a city of its own. The corridor became an internal street; families crowded into the individual rooms.”

Past zoning laws rightly addressed this overcrowding of families. But as we move into the 21st Century, we now have a new housing imbalance to address. Longer lifespans, changing social norms and other factors have greatly increased the percentage of apartments occupied by a single person or unrelated adults living together. What’s more, New York is no longer the dirty, dangerous place it once was, and spending leisure time in public spaces has become an essential quality of urban life.

To address this mismatch between housing and demographics, under Mayor Michael R. Bloomberg, we developed the adAPT NYC micro-unit pilot project. By removing the 400SF minimum unit size requirement we inspired architects and developers from across the globe to think big about living small in NYC.

Fast forward to 2016 and under Mayor Bill de Blasio, ZQA takes a much bigger leap by abolishing the 400SF minimum altogether. Creating micro-units within multi-family buildings will now be a standard building option as long as it has a mix of larger units, ensuring that the city has a variety of apartment options for families of all sizes.

Medium: Designing a Better Street-level Pedestrian Experience

From an urban design perspective, how buildings meet the sidewalk is the most important question of all, since it is at the street level where people actually experience the city.

We completed a comprehensive study in 2013 as part of our Active Design work called Shaping the Sidewalk Experience. Recognizing the importance of the sidewalk as our primary public space, we conceptualized the sidewalk as a three dimensional room to show how the building plane, especially the first one-to-two floors, affects the pedestrian experience.

As with micro-units, ZQA is attempting to address this small but important part of a long-simmering urban design challenge. In 1990—when American cities were just beginning to recover from the ravages of post-war abandonment and urban renewal—Richard Sennett squarely identifies not only the problem but also the cause of deadened street life in The Conscience of the Eye.

“Today, the principle of disrupted linear sequence, the street of overlayed differences, is an elusive reality in urban design,” writes Sennett. “An architect seeking to create a building possessed on narrative power would seek one whose forms were capable of serving many programs. This means spaces whose construction is simple enough to permit constant alteration …” This lack of flexibility and layering of uses quashes street life, which ultimately results in the disconnection of people. The consequences of this disconnection are not inconsequential, contributing to abandonment, a lack of community resilience, social and economic distress.

Mayor de Blasio’s commitment to building significant affordable housing without sacrificing our public realm provided us an opportunity to fix a zoning issue that contributes to this problem: Many affordable housing developments often resulted in ground floor spaces that didn’t work for most retailers, or worse, created a deadening streetwall. Trying to squeeze in as much affordable housing into a tight building site often short-changed the ground floors, severely limiting their ability to serve “many programs,” as Sennett writes. ZQA adds just a few feet of additional height to the overall building, which is a worthy exchange for a well-designed street front.

ZQA also gives architects and developers the needed flexibility in designing the building envelope to make it easier to provide outer courts, bay windows and other architectural features found in some of our most beloved buildings. These features were difficult, if not impossible, to provide under the rules as they were previously written.

Moreover, old zoning codes treated every site as if it were a perfect rectangle. With additional flexibility, ZQA allows architects to design for irregular lots—which most of them are—without sacrificing space. And it’s those irregular spaces that make buildings unique and interesting, giving them, as Sennett would say, “narrative power.”

The complicated relationship between zoning and design is felt at the street level, but it has an even greater impact on the function of the whole city. In addition to the need to accommodate more affordable and higher quality housing, ZQA also incentivizes a range of affordable senior housing and care facilities to meet the needs of an aging population. ZQA also mitigates the high costs of building affordable housing by eliminating outmoded parking requirements in transit-rich zones. Since we last rewrote the zoning codes, urban designers have come to realize that when the city prioritizes the automobile above all else, the city does not work as well for people.

Large: Shaping a City for the Present and Future: What’s Next?

For good reason, previous zoning codes mostly eliminated mixed-use neighborhoods. People rightly did not want dirty factories next to their homes. The post-industrial city does not have this problem at nearly the same scale as it once did. Like demographic shifts, this too has been a change long in the making.

“Time begins to do the work of giving places character when the places are not used as they were meant to be,” writes Sennett. “To permit space to become thus encoded with time, the urbanist has to design weak borders rather than strong walls. For instance, a planner hoping to encourage the narrative use of places would seek to lift the burden of fixed zoning from the city as much as possible, zoning lines between work and residential districts, or between industrial and office workplaces.”

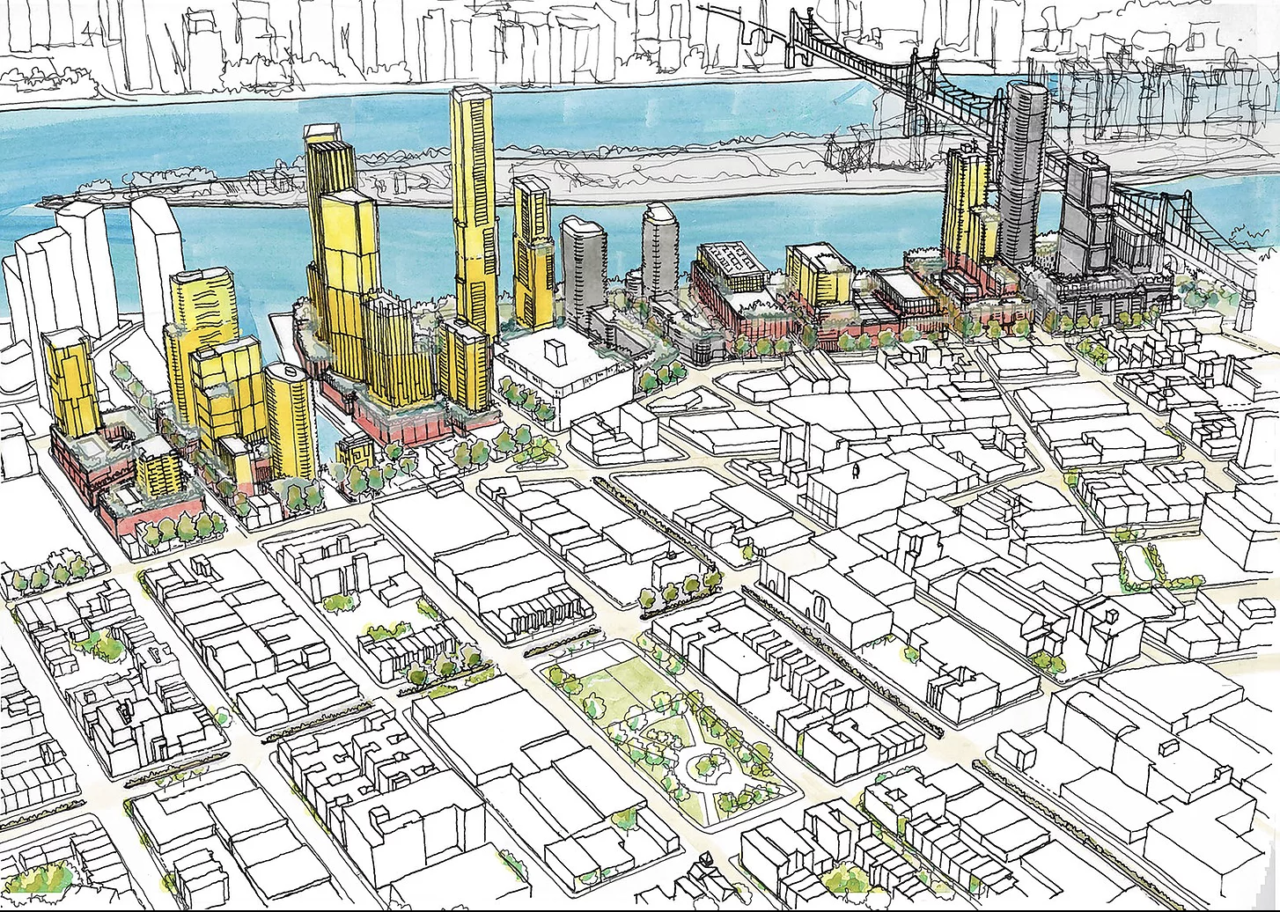

All zoning code changes in ZQA, very much motivated by the lessons articulated by Sennett, came out of a long process of observation, social research and pilot projects. But how do you run a pilot project at the neighborhood scale? How do zoning changes factor in the quality of time? That is what the city will find out with a new mixed-use initiative in Long Island City that is not part of ZQA but will surely influence zoning code changes in the future.

The city’s Economic Development Corporation has received nine proposals for what will become New York City’s first 21st Century mixed-use neighborhood. With an eye towards complementing the nearby Industrial Business Zone, the growing tech sector, residential uses and new urban amenities, a section of Long Island City will benefit from a rezoning and a new set of design guidelines that allows for a much greater mix of uses.

As just one example, the design guidelines encourage loft-like buildings—not just for “loftominiums” but for a true mix of uses, for both living and working. The city isn’t just seeking a contextual “look” but real context. Like Richard Sennett, we believe that what makes a neighborhood interesting is how it functions and not just how it looks.

The design guidelines also encourage spaces for light manufacturing; public spaces along the waterfront that do double duty in terms of resilience and connectivity; and a wide variety of flexible ground floor configurations to catalyze as many different uses as possible—and of course affordable housing.

We don’t yet know how the design guidelines will play out or how the neighborhood will develop over time. As much as we try to predict the future, cities are incredibly dynamic and constantly changing, and this is certainly true for New York. But, as we celebrate the 100-year anniversary of the city’s first zoning resolution, we should also celebrate zoning’s ability to persist and adapt, providing a framework that allows for constant change, from the seemingly small to the very large, and in many ways inseparable from the great city that we love.

Jeffrey Shumaker is the Chief Urban Designer for the New York City Department of City Planning

Lisa Chamberlain assisted with this essay. She is a communications consultant working with professionals engaged in designing the built environment.