by: ac

Charles Montgomery’s book, Happy City: Transforming Our Lives Through Urban Design (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2013), is essentially a mind mapping of the current issues, policies, and conundrums of the North American urban design landscape. Montgomery deftly balances the likes of Socrates, Aristotle, a variety of sociologists, politicians, psychologists, and a hand full of architects and urban designers to gauge and assess the city via various forms of happiness data. He uses a dizzying array of personal anecdotes, and takes the reader through city after exurb after cul-de-sac to illustrate the dire straits that Americans, in particular, are in. While I admire the stylistic attempt to weave together these many disciplines, the result feels confusing and a bit too polite.

Although the device of measuring the success of cities against scientific data makes sense, I think that Montgomery wrote a different book than he intended. At face value, yes, he wrote a journalistic account of what makes people happy in an urban setting, but he doesn’t successfully define happiness. Actually, the overriding theme is the concept of freedom. More specifically, America’s co-dependent relationship with car culture – the car in American mythology being an icon of freedom, but in actuality it is an instrument of economic subjugation. Montgomery at his best defines freedom – freedom as sharing space; freedom in knowing and trusting your neighbors; bicycles as freedom in a crowded city; freedom as proximity to nature its impact on urban space; the freedom to treat a streetscape in a malleable manner; and, most intriguingly, the freedom to change zoning laws.

Montgomery starts his telling of tales with his visit to Bogotá and its mayor Enrique Peñalosa. As the book unfurls, Montgomery finally states that Peñalosa’s civic agenda is an all-out war on the automobile. The genesis of the mayor’s redistribution of city moneys to transportation and public space rather than freeways was a very intentional act to refuse money from Japanese industry that wanted Bogotá to be more dependent on the car.

Montgomery’s account of the Atlanta suburb Mableton is extraordinary; I want a documentary, more books – anything on this story. He uses Mableton to feature the work of New Urbanism at its best, and brings forward Galina Tachieva’s book Sprawl Repair Manual. The idea of sprawl repair sounds like groundbreaking innovation. Montgomery juggles with the New Urbanists’ allegiance to old-school vernacular, and illustrates its Disney-like constructs, but ultimately Mableton is a wished-for, intimate place of high density and social exchange.

Montgomery’s hometown of Vancouver pops up in all its glory every other chapter. Vancouver is clearly a great example of a walkable city, but to put it next to Atlanta as the “bad city” is naive. Atlanta’s racial history since the Civil War has made it ground zero for most of the changes that had to happen in the American South; the car is a class symbol, and at its worst a tool for segregation. Atlanta’s intense climate has made the car more than just a prop for laziness, it is a refuge from the heat and humidity that is three quarters of the year in the South. If Atlanta was set in the bucolic mountains of the Northwest, its dependency on the car would not be so intense. Mableton will show the way, but it’s not easy.

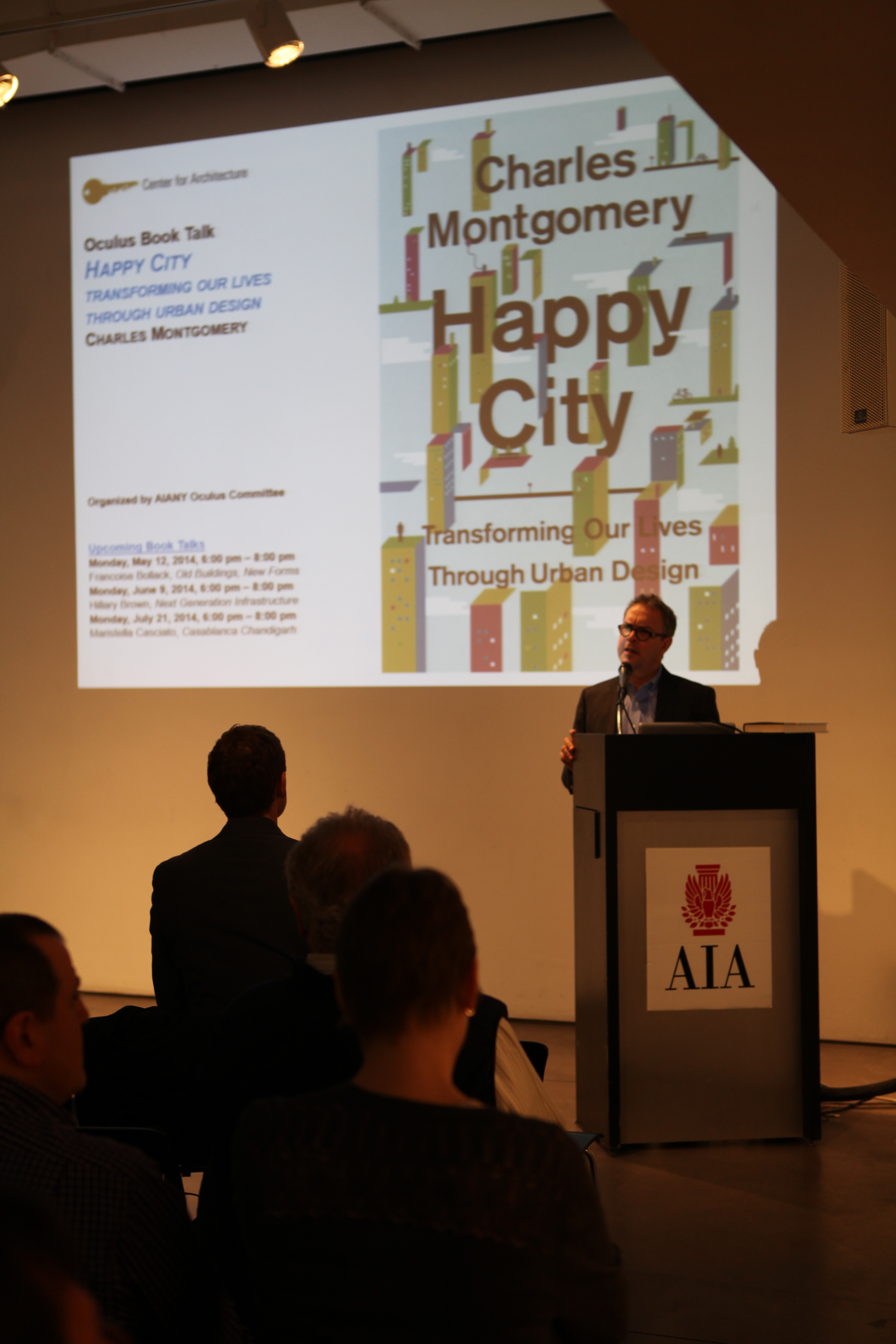

In Montgomery’s Oculus Book Talk, he showed his work from the BMW Guggenheim Lab. This was an interesting and innovative set of experiments, and let’s say “freedoms,” in order to gauge happiness. His presentation at the Center for Architecture was focused and clear and paved the way for the argument that a nation’s GDP is not a gauge of success, but happiness data might give real signals to the success of urban place. Ultimately, Montgomery is an advocate for small acts in urban conditions as acts of vital change, and is an optimistic force in this argument for change. But for all his dashing about the world finding examples of change, I wondered about the house he started to rehab on the urban edge of Vancouver, and how the process did not make him happy; he wanted more. This book is about a search for freedom from consumerism, and in that freedom, perhaps contentment could prevail.

Annie Coggan is a principal with Coggan and Crawford Architects, and teaches at the Fashion Institute of Technology and the School of Visual Arts in New York City.

Event: Oculus Book Talk: Charles Montgomery, Happy City

Location: Center for Architecture, 04.07.14

Speaker: Charles Montgomery, journalist and author, Happy City: Transforming Our Lives Through Urban Design

Organizers: AIANY Oculus Committee